William Boyd: Death, drugs and doppelgängers

William Boyd is no stranger to double lives and double dealing – and in his latest chase thriller of a novel, he exposes the dark side of the pharmaceuticals industry

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Chelsea, with its affluent, cultivated surfaces, is hardly a hackneyed habitat for the hunted and down at heel. Walking along the embankment before I careen off into one of the most desirable postcodes in the country, I glance at the copse next to Chelsea Bridge. It is in that dense triangle that William Boyd has his hero go to ground in Ordinary Thunderstorms, the author's barrelling follow-up to his hit spy thriller Restless. I wonder if perhaps it might just be the perfect place to disappear. After all, isn't it meant to be calmest in the eye of the storm? The rich don't look twice at the soiled beggar by the deli door.

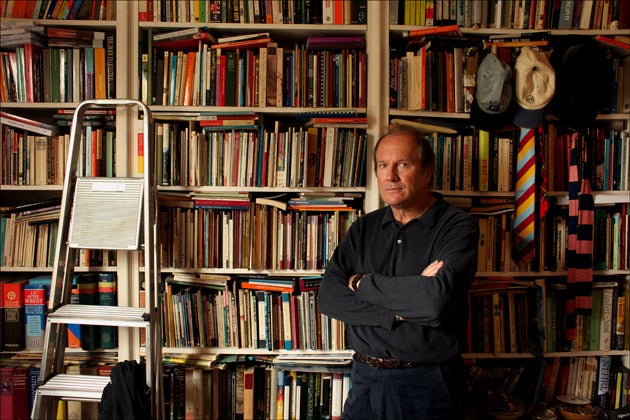

Interviewing Boyd in the lounge of his townhouse – he's lived in Chelsea for more than 20 years – is a congenial experience. He is a garrulous, jovial and diverse conversationalist. Surrounded by a striking art collection that illustrates his obsession with articulate artifice, he has, in his conversation, the same beguiling storytelling ability that imbues his fiction – what Graham Greene would have termed "entertainments". He has the air of a polymath keen to draw his listener into his varied and nebulous worlds.

In Ordinary Thunderstorms, Adam Kindred is "a cloud man" with a problem. He is a climatologist who finds himself wanted for the murder of an immunologist he briefly encountered in an Italian restaurant. There are a lot of "ists" in Boyd's fiction. The dead scientist was developing a miracle cure for asthma, a drug that is set to earn his pharmaceutical company untold riches and the secret of which Adam unknowingly possesses. His life spirals out of control as a cast of assassins, river police and corporate flunkies hits his trail.

It is a book, I tell Boyd, which harks back to that early 20th-century tradition of the chase thriller. The type that are loved by the English: a middle-class protagonist, a good sort with a profession and a wry take on proceedings, finds himself tumbling into the machinations of some dastardly plot. Think The 39 Steps, The Riddle of the Sands or, most pertinently, Geoffrey Household's Rogue Male. Household had his hero holed up in a 1930s bucolic Dorset vale. Boyd's scenario has the pursued dealing with the perils inherent in the trappings of City life in the Noughties. The electronic and paper trails that tally our metropolitan existence could prove Kindred's undoing. "That's how you disappear in the 21st century," he quickly realises. "You just refuse to take part in it."

"All my novels cherry-pick a genre to provide a narrative motor," says Boyd. "And you're right, there is that man-on-the-run concept, like in North by Northwest, the central character in jeopardy. It draws on all these narrative traditions. But really there was a novel lurking in the back of it and that's Our Mutual Friend, which starts with a body being removed from the Thames." Much like Dickens' mystery, Ordinary Thunderstorms is very much a London novel and Boyd clearly states this as his intention. It's steeped in the capital's snags and lures, beauty and banality. "It's not like Zadie Smith's reworking of EM Forster," he explains. "It's not that kind of template. It's more the Thames, dead bodies, London, every stratum of society..."

The river runs like a dark seam through the story and possesses a grisly undertow. "I read in an article that they are still taking 50 to 60 bodies a year from the Thames; that's over one a week, yet we hear only about the gruesome, ghoulish voodoo murder," Boyd says. "That's a lot of dead bodies and that's what set me going." London, he once wrote, poisoned him with insomnia and allergies. He declared it "a tax my body has to pay if I want to live in London – the most interesting city on the planet". To some extent his new novel is a kick at the city and the sham remedies that demand such a heavy levy.

Boyd's own counterfeiting skills reached their zenith in the late 1990s with the publication of Nat Tate: An American Artist, his monograph of a phoney abstract expressionist. Tate was supposedly a contemporary of Pollock and De Kooning and was notorious for destroying the majority of his output before committing suicide. Or rather, he would have been had he ever existed. "We had this huge party to launch the book in Jeff Koons' studio in Manhattan on 1 April 1998," laughs Boyd. "The art correspondent of The Independent, David Lister, who had become one of the conspirators, went around this party asking leading questions of all the glitterati and intellectuals. And anyone who was anyone would be saying, 'Yeah, yeah, Nat Tate, I know him, I went to one of his views...'"

The hoax to some degree became reality when you consider that Boyd (who originally intended a life focused on canvas) painted "Nat's" works. In his front hallway hangs a series of line drawings, signed by the fictional artist. "Well, they are rare and they do have a provenance," Boyd points out mischievously.

It is this disconcerting form of creative ventriloquism that Boyd has perfected over a career spanning three decades and 16 books, including novels, story compilations and an exhaustive collection of journalism. He acknowledges that several novels have deliberately toyed with supposedly genuine events and characters and their reportage. "I can look back now and see there are three books I tried to do the same thing with: The New Confessions, which is a fake autobiography; Nat Tate, which is a fake biography; and Any Human Heart, which is a fake intimate journal. In each case they are mixing the fictive with the real."

Identity, character reinvention and the dubious deeds of doppelgängers and dupes have always ornamented Boyd's tales. And Boyd himself possesses a mirror life. For years he has wooed the fickle mistress that is the movie business. With one directing tag under his belt, for his First World War drama The Trench, and numerous screenwriting nods, he reluctantly accepts that the industry is now shaped by "perverse industry mantras". With ageism and jingoistic restraint pervading Hollywood, he has found himself repeatedly let down by its ever- narrowing vision. "Why would you want to hire 'an old guy' when you can hire a 25-year-old who has done this rock video?" he asks mockingly. His current cinematic project is an intriguing adaptation of the DH Lawrence short story "Love Amongst the Haystacks", which Boyd has relocated to the American Midwest in the 1920s and describes as "a heterosexual Brokeback Mountain". Yet it's currently floundering in production purgatory after the original Australian director was deemed "uncool" by financiers.

Boyd concedes that book publishing is showing signs of the same lack of imagination. "I think it does trickle down," he says. "The retail side of publishing has changed so much. One publisher said to me: 'We've lost the war. The retailers have won.'" However, marketing hype and funnel-promotion has recently done wonders for Boyd. After Restless was chosen for the Richard & Judy book group, he found himself with a runaway bestseller at an age when most authors find their sales on the wane. The book went on to win the Costa Prize for the best novel of 2006.

Of course, tapering commercialism will always benefit the few. Such monopolies shape Ordinary Thunderstorms. Like John le Carré's The Constant Gardener, the novel nails the sheer immensity of the pharmaceutical racket, an industry teeming with more chancers and financiers than physicians. "Look at Tamiflu and the amount of money [its manufacturers] will make. Every time somebody says pandemic on the television, they must just go, 'Wow!'" states Boyd, punching the air. "The amount of money these blockbuster drugs make is phenomenal. It almost makes the arms industry look benign."

Murdering medicine men are a perfect Boyd conceit. In explanation, and like the Chelsea morning sun glinting off the graphic-lined canvases behind him, he accentuates the dark parameters of his work: "At the end of the book it hasn't turned out as it should have. But then that's life, isn't it?"

The extract

Ordinary Thunderstorms, By William Boyd (Bloomsbury £18.99)

' ... The only way to avoid detection in a modern 21st-century city was to take no advantage of the services it offered... If you made no calls, paid no bills, had no address, never voted, walked everywhere, made no credit card transactions or used cash-point machines, never fell ill or asked for state support, then you slipped beneath the modern world's cognizance. You became invisible.'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments