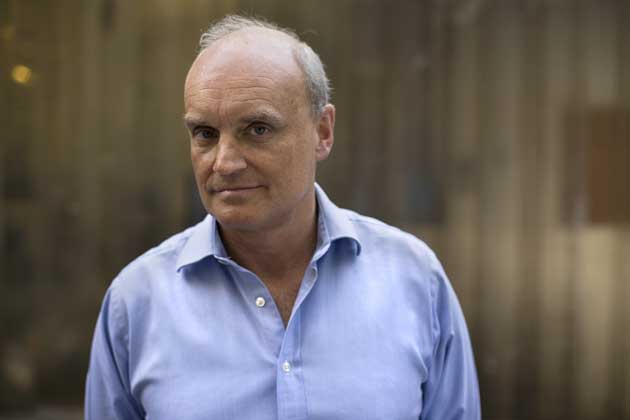

The view from the top: Condé Nast grandee Nicholas Coleridge's blockbusters are anything but elitist

Nicholas Coleridge could have followed his father into banking at Lloyds. Instead, he runs a glossy magazine empire and writes glossy novels about old money, new money and Tory spin doctors

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Today is St George's Day, and Nicholas Coleridge and I are sipping champagne at the pavement table of an exclusive Mayfair club. It's a beautifully English, brilliantly sunny spring evening. And if anyone knows a thing or two about Englishness and exclusivity, it's Coleridge, for many years the man at the helm of the glossiest of glossy magazine empires, Condé Nast. Vogue, Tatler, GQ, Easy Living, Traveller and Glamour are just a few of his titles.

But something very weird, possibly very English, is happening across the street. A large group of middle-aged men, all wearing red ties and shabby, dark suits have congregated outside the Audley pub. They are being particularly boisterous. "My God," says Coleridge, "look at them in their red ties. It's a very particular English look. I wonder what they all are – actuaries?"

Aside from his Condé Nast credentials, and the fact that his father was once chairman of Lloyds, Coleridge is an acutely perceptive observer of people and places, not to mention of people in their places. For many years, this most successful of magazine publishers has also been penning chunky, bestselling novels. They are not quite bonkbusters, but nor are they Madame Bovary. Think of a slightly less randy Jilly Cooper, but a much more fun Joanna Trollope (whose books he professes to love reading).

Coleridge's recent novels – Godchildren, A Much Married Man and the latest, Deadly Sins – are, as he says, "epic stories that tend to run over 10 or 15 years; multi-character; quite English; family sagas with a twist of power and revenge". And while they are invariably packed with, or at least patrolled by, alpha males, they go out of their way to feature well-drawn and often complicated women. In many ways, Coleridge is writing classic, middle-market female fiction. The only twist, or slight deviation, is that there tends to be more emphasis on power than sex or romance. Yet issues of family are never far away.

Not surprisingly, Coleridge spends most of his working life with women – of the 600 people he employs at Condé Nast, only 90 are men. "It's a great compensation for not having gone into the financial world, where I would have been sitting in a dealing room with 800 blokes." While he admits that his wife Georgia, a children's book reviewer and writer, "is very good at helping me build up female characters", you get the impression that it's not because of his own neglect.

Indeed, it is hard to imagine Coleridge ever purposefully neglecting anything. A Cambridge-educated Old Etonian, with a bloodline wavering right back to Samuel Taylor Coleridge, he's almost outrageously polite and attentive. Or perhaps he's simply in possession of very good manners, when so many people are now not. But, legendarily, he is not averse to a good gossip – you don't get the impression he ever forgets a name – or having a chuckle.

The action across the road at the Audley is hotting up, with the arrival of two glamour girls – their Lycra-clad bodies sporting Spearmint Rhino logos. One of the actuaries is mooning, while another is giving a lap dancer a piggyback ride across Mount Street. "This is very funny," says Coleridge. "Actually it's hilarious. What a brilliant promotion. You suppose Spearmint Rhino know how to target an audience."

At Condé Nast, Coleridge spends his whole time identifying and maintaining niches, while as an author he also has a fairly clear vision of where his reader lies. "I always assume I am writing for a combination of the higher end of the Daily Mail, coupled with the Daily Telegraph meets The Independent." I'm not sure whether he chucked in the Independent reference for my benefit, but he quickly adds, "It's an educated readership but it's quite broad."

It's also, by his definition, a broadly conservative readership (excepting, conceivably the Indy brigade). To talk to Nicholas Coleridge, to have just the briefest ideas about his background, it's not very hard to label him a privileged toff. Yet that would do both the businessman and the writer a big disservice. Deadly Sins effectively charts two warring families. Sure, it's about, as Coleridge says, "power and rivalry and envy, with sex as a sort of amusing wheeze", but it's also about England during the past decade; the left and the right.

Alpha male number one is Miles Straker, a Tory spin doctor-cum-PR supremo who made a packet and a pile during the Thatcher years, and is now enjoying the fruits. His mouse of a wife Davina and four underage and oversexed kids are variably paying the real price. His nemesis, who has the audacity to move into first the same Hampshire valley, and then Holland Park Square, is Ross Clegg, a frozen-supermarket tycoon who's both a die-hard socialist and a sudden, roaring success. But Clegg's pasty wife Dawn – the "scrubber" as Miles calls her – and three trembling kids are also made to pay a hefty price for their old man's social mobility.

"If I was being pretentious, which I wouldn't normally be, I wanted to write a book about the last 12 years, and try to have characters that weren't completely obvious," he explains – "in that it's Miles, who is a Tory spin doctor, who comes to a bad end, and it's Ross who comes to a good end. I also quite like the way that some of the Clegg family are good and some bad, and some of the Strakers are good and some are bad."

While Coleridge says he's interested in how people's characters and lives change depending on certain circumstances, invariably the thing driving this change is power, or influence, and money. He says Deadly Sins is a book about "old money and new money", though the "old" money is not all that old. "I think money/class is so blurred now. Britain has changed hugely, and I guess one of the themes of the book is how fast people can too."

As Coleridge says, it's a book about social mobility, people starting in one place and ending in another, for which he drew inspiration from the numerous PR maestros, retail tycoons and financial wizards with whom he has long associated. A number, such as Philip Green, even enjoy walk-on parts. And when short of facts and figures he simply asks the best. Madonna's divorce lawyer, Fiona Shackleton, no less, provided him with details regarding divorce proceedings when he was mapping out Miles's demise.

That the big Tory bully eventually and spectacularly gets his comeuppance, thanks to the vision, persistence and fairness of the little socialist from up north, and at a time when the Tory party is in resurgence, seems an unlikely, off-message ending. However, Coleridge insists that all his novels are purely sociological and not really political. "It's a family saga at heart and a large part of my audience are people who like reading about family sagas."

Another slice of his audience – incorporating those highly influential friends – must be more than aware that Coleridge is a very good-humoured chap with a fine, and now lucrative, sideline in satire and parody. His last novel was a number-two bestseller, and his sales figures have been increasing with every book. Amazingly, he only works on his novels on early weekend mornings, at his country pile in Worcestershire. Weekdays are taken up with Condé Nast business, Chelsea living, and, as for his four teenage children, well, they are either away at boarding school, or at home in bed.

"I'm lucky," says Coleridge, who's 52, "in that I still have quite a lot of energy. And writing fiction is a different energy, using a different part of my head." He loves Condé Nast, and by all accounts Condé Nast loves him. "But one day," he says, "and it's quite a long way off, I'd like to write full-time." Though of course far too polite to brag, he's immensely proud he's built such a big, broad audience – even he can't have that many "friends". "If somebody says 'I read your book by a pool in a hotel, in three solid days,' that is, to me, the ultimate compliment. That's what I'm aspiring to."

With the Spearmint Rhino ladies long having departed Mount Street, Nicholas Coleridge nips off to his waiting limo. And he's the chap who could so easily have followed his old man into Lloyds and been an actuary. I can't help but think that not only has he long enjoyed life on the right side of the street, but that he, and we, have increasingly benefited from the view. n

The extract

Deadly Sins, By Nicholas Coleridge (Orion £12.99)

"... At lunch, he lectured Davina and the children on the importance of cultivating relationships with well-placed individuals, and that through a judicious balance of hard work and discreet networking it was... possible to achieve everything you wanted. 'Call it a life lesson,' Miles declared, as his family sat around the mahogany dining-room table"

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments