The unfinished books that writers can't put down

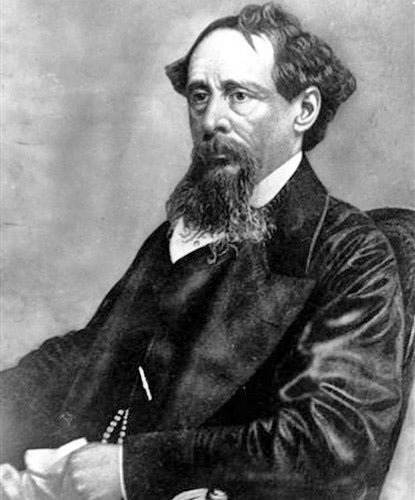

The latest attempt to complete Charles Dickens 'The Mystery of Edwin Drood' follows a great literary tradition, reports Alice-Azania Jarvis

It has occupied playwrights and publishers, journalists and spiritualists. And now the screenwriter Gwyneth Hughes – renowned for her work on the gritty thriller Five Days, and the period reconstruction Miss Austen Regrets – is to try her hand. In a costume drama to be broadcast on BBC Four later this year, Charles Dickens’ great unfinished novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, is to be “completed” and adapted for the small screen.

Using evidence left behind after Dickens’ death in 1870 – including a plot outline he gave to his great friend and biographer John Forster – Hughes will pick up where the author left off, deciding who killed (or attempted to kill) Drood, and how the saga concludes.

It’s not the first time Edwin has been subjected to such interference. Just a few months after the author’s death in 1870, the American satirist Robert Henry Newell published a continuation of sorts. Along the way, though, he moved the setting from England to New York.

Shortly afterwards the journalist Henry Morford offered his take, while in 1873, a Vermont printer Thomas James went through the rigmarole of channelling Dickens’ spirit to find the “authentic” ending.

The result was panned by critics but received at least one nod of approval, from fellow spiritualist Arthur Conan Doyle. A musical adaptation, meanwhile, in which the audience votes on who they think is the murderer, notched up five Tony awards during its run on Broadway.

What, one wonders, would Dickens’ make of all this? History is littered with great unfinished novels, not all of which are best suited to a third party’s tinkering. When Vladimir Nabokov’s son published his last novel The Original of Laura, he was met with stern criticism. Not only had the Lolita author expressly forbidden that any incomplete manuscripts be retained on his death, but the text was attacked as the work of a man past his prime. Better, said observers, that Nabokov Jnr had never got involved. JRR Tolkien’s The Silmarillion met with similar hostility. Pieced together by the author’s son, Christopher, with the help of the fantasy writer Guy Gavriel Kay, it was described as inaccessible and lacking a band of empathetic characters.

But perhaps we shouldn’t be so harsh. As Dr Daniel Cook, English Literature Fellow at Bristol University, points out, many of the works we know and love received a helping hand or two from outsiders. “Jane Austen is a prime example of someone whose work has been heavily edited – and published posthumously,” he said.

“It may not have been a matter of ‘continuing’ them, but if they hadn’t been tampered with them, we wouldn’t have Jane Austen. The same is true of Kafka. Not only did Max Brod publish his works posthumously, but altered them posthumously too. ”

Indeed, the allure of the unpublished novel is nothing if not potent. Despite the millions of books already available, news of an undiscovered work by one of history’s best-loved authors – even in an unfinished state – is difficult to resist. Who didn’t experience a thrill of anticipation when Joyce Maynard, one-time partner of JD Salinger, claimed that her former lover had been furiously writing long after his final published work, the rambling short story Hapworth 16, 1924? And who wouldn’t want a glimpse at the enigmatic Harper Lee’s unfinished The Long Goodbye?

“With certain authors – especially Dickens – there’s a sense of discovering a hit,” observes Dr Cook. “It’s like a record collector discovering a Beatles song. It’s tried and tested: you know it will be good.”

And so it was that The Last Tycoon, the final novel by F Scott Fitzgerald, was collated by his close friend, the literary critic Edmund Wilson, from left-over notes. It went on to win renown for its authoritative, potent depiction of Hollywood life. Likewise Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities, which weighs in at some 1,800 pages long despite Musil’s failure to complete it – it has since become a heavyweight classic. Add to those Roger Martin du Gard’s Lieutenant-Colonel de Maumort and there is a veritable canon of incomplete work which is still worth reading.

So what to expect of the BBC’s latest attempt on Drood? Crucial to the success of Hughes’ adaptation, says Cook, will be the extent to which it acknowledges its status as just that – an adaptation.

“It all depends on how the BBC spin it,” he says. “It’s an augmented version, rather than the real thing. When Charlie Higson or Sebastian Faulks publish a Bond novel, it’s very much ‘Higson’s Bond’. The series remains Ian Fleming’s baby. Hughes should do the same.”

At very least, the programme will open up Dickens’ work to a new and wider audience: it is for those acquainted with his big-hitters as well as for those to whom his entire catalogue is alien. As it is part of the BBC’s “Year of Books,” that, after all, is surely the point.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks