The undiscovered Laurie Lee: Two previously unknown essays on London and rural life

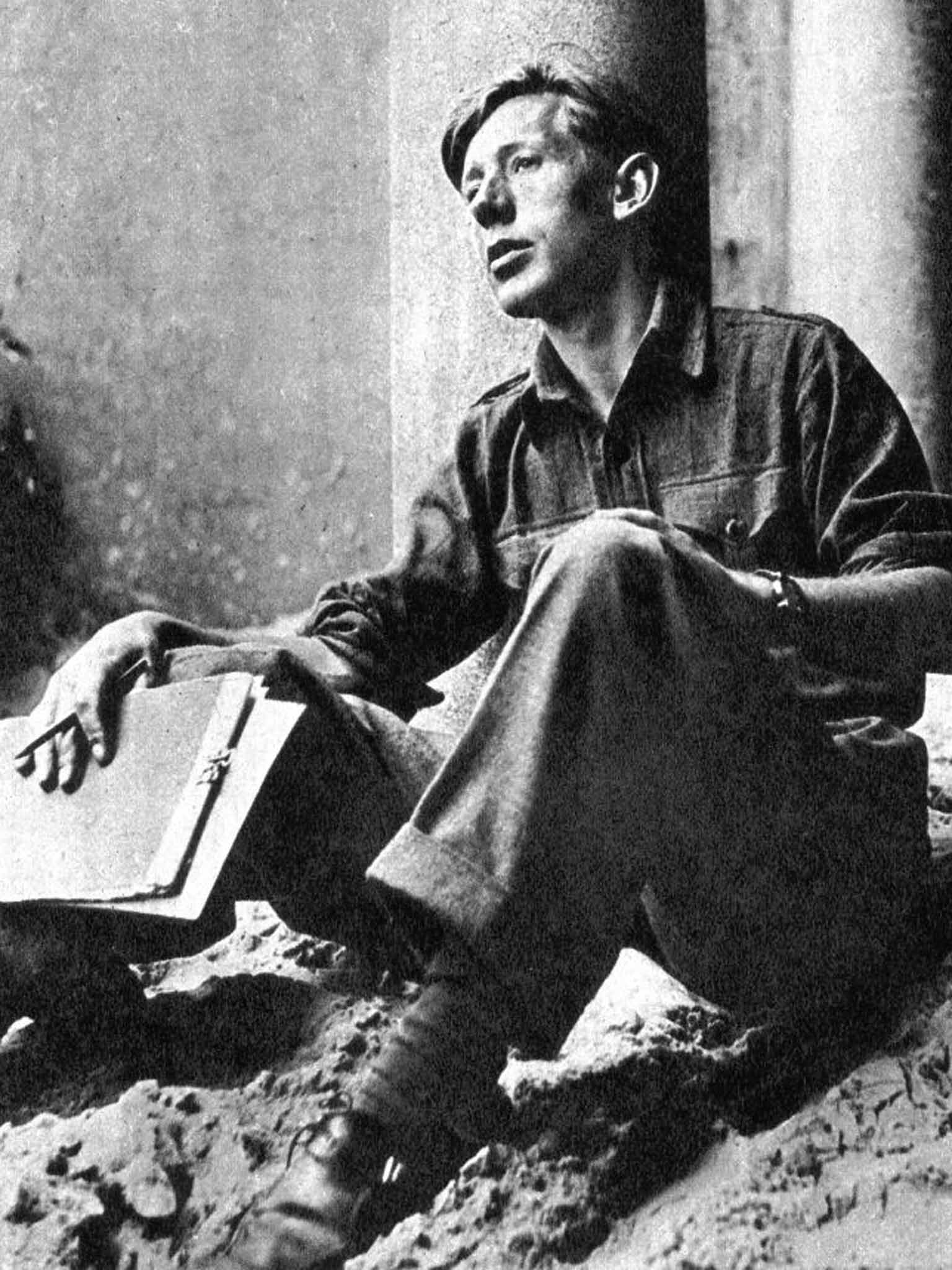

A century after the author's birth, some of his private papers are being published for the first time. Here, his only daughter Jessy Lee introduces two previously unknown pieces: one on familar rural territory, one from wartime London

I was perplexed when the day came for Dad's papers to be removed from the house. My mother and I had been encouraged by the trustees of Laurie's literary estate to find a home for the archive not long after he had died. I had mixed feelings – relief that the papers were going to be housed “just up the road” at the end of the A40 in the British Library, and, of course, a sense of loss at seeing the empty room left behind.

As a child, I was only allowed to go into Dad's private study on rare occasions and after he died I respectfully developed an aversion to going through his papers. I was wary of disturbing the precarious sculptures that he'd mapped out for himself: he knew where everything was in an instant – a master of Pelmanism.

It was some years later, in 2011, when I had begun to think about Dad's forthcoming centenary in 2015, that I found the courage to anonymously visit the archive. Although I was excited to secure my reader's ticket, I was a bit nervous about stepping into this forbidden world. I felt like a spy, creeping about in the muted aisles of the readers' room. This arena was not something that I was used to and I struggled with the complicated process of ordering manuscripts. I found it hard to resist the urge to say, “I'm his daughter for goodness sake – just give them to me!”

Eventually, I sat down with my treasure and was immediately scolded for not holding the papers correctly. My impulse was to giggle nervously, but I pulled myself together and opened up the folder.

The first thing that hit me was the musty smell of Dad's study. I couldn't believe that the scent had survived within the vaults after all those years. It was as though he was there. I suddenly felt a wave of grief and could barely stifle the tears. But the grief turned into intrigue and intrigue into excitement as I began to immerse myself.

As I read, I began to develop a new, fresh relationship with Dad's writing. I read poems that I had never seen before and pieces of prose that were published long before I was born. The more immersed I became the more I realised that a book of these works must be published, so that I could share these beautifully crafted pieces. I wondered if Dad would have approved of my publishing a new book in his absence – but then he did leave it all behind.

One of the pieces that first struck me was from his essay “Letter From Britain”, where he describes watching starlings in London:

“They swept the sky like bursts of grape-shot, they bombarded Nelson's statue with black confetti, they settled thick on rooftops, then blew away like dust. Londoners, homeward bound from work, missed their buses and almost got run over, standing to see the sky above them all veiled with birds like a storm that never broke.”

I was particularly taken by the way he uses such dark, menacing comparisons to describe something so mesmerising and uplifting. He had such an ability to move one between extremes, and he does just that so tantalisingly throughout these essays.

In another essay, “Notes on England”, I was transported back to my childhood in Slad by Dad's colloquial humour: '“Couldn't sleep last night,” I heard one of them say, “for the sound of snails crawling under low bridges.”' This just makes me laugh!

There is so much more, of course, and it is hard to pick a favourite piece. But now the dream I had of bringing these wonderful pieces of writing to the public has at last, been realised and I couldn't be happier that this new book, Village Christmas, is to be published by Penguin Modern Classics. I think the celebratory success of Dad's centenary helped to remind us all of just how much Laurie is loved and respected for his craft with words.

Lee in the country: As-You-Were-Only-Better

They remember me best as I went away, more than a quarter of a century ago. I left as a turnip-faced grinning oaf, and returned last year, a bag-eyed poet, having in the meantime written a book about them.

“Better mind what you say. He'll put you in writing. Done it before. His poor old mother . . .”

Of course one should never have gone in the first place. It is never really forgiven you. And to revisit one's roots calls from an upside-down posture which too often proves that the plant is broken.

After twenty-five years I find the main changes in me and in the villagers' view of me, but the village itself has come through the revolutions of that time with fewer abrasions than I would have expected.

The place is called Slad and lies some two miles from Stroud in a bent and secretive valley. The valley is steep, and usually running with rain, and some say you can't sleep, in really typical weather, for the noise of snails crawling under low bridges. There used to be cloth mills along the valley bottom, sturdy and prosperous places, but they were all washed away in a great night storm in the early nineteenth century.

I lived in this village until I was twenty and till then knew no other world. I remember it as a place of long steamy silences, punctuated by the sounds of water, by horses' hooves and mowing machines, sleepy pigeons and mooning cows. Of the thirty-odd families living in the straggling cottages, some worked on the farms, some at the mills in Stroud, but most were in service to the Squire. Wages were small, and families large, and there was a tendency to live off the land – wild fruit was bottled, blackberries gathered, pigs kept, fowls raised, rabbits hunted, pigeons trapped, and flowery wines home-brewed in abundance. There was also an intense and vivid communal life, much preferred to outside allurements, with choir-outings, concerts, harvest festivals, feasts, penny-dances and junkets galore. The neighbouring villages were thought to be full of savages and we beat them if they came our way; Stroud was the market, but shark-infested; in any case transport was poor. For the most part we stayed in our tight green valley, as snug as beans in a pod.

How is it now? Visually it's changed very little, maybe a bit better scrubbed round the lintels, but the village still lies in its tree-crammed corner folded deep in the valley's cool. People move about more, most have some kind of car, and will visit the neighbouring villages with impunity. But the long steamy silences can still recur, when everybody seems to have taken cover like moles.

There are fewer children, but much better dressed, and fewer, if any, rabbits, and the stretches of common where they once both swarmed are now overgrown with brambles. Living is tidier, more genteel, more opulent; the pet dog has replaced the pig, the wild plum and apple are left to rot on the bough, the fat blackberry gluts the hedgerow ungathered. With the fading Church and the decayed Big House much of the old communal life has gone.

Certain traditional evils have also gone with it – the damp and the cold, poverty, malnutrition, epidemics and early death. Better farming, better shops, better jobs and more money have brought the best changes of all. There is less hunger now, less sheer animal drudgery, people have time to straighten their backs.

Until recently the village lived by oil lamps and wood fires, and cottage windows glowed warm in the dark. Now electricity has come, with its crazy cat's cradle of pylons, and the place is bright as a surgeon's knife. One must approve of this; one can also regret; much has been gained but something lost – the shadows in the corner which fed the poetry of children, and a certain thousand-year-old self-sufficiency (for instance, when lightning cut the current the other morning many cottagers couldn't even make a cup of tea).

Electricity and piped water are common boons now, but the villagers have been busy with other improvements. These are the details of change, invisible from a distance, but part of the modern purge. Broken-down old cottages have been stiffened with concrete, roofs rain-proofed for the first time in centuries. The family car has condemned many an ivy-clad wicket gate (together with the grandmother it used to prop up) in favour of jazzy contraptions – metal tubing smart enough for an aerodrome.

Cottage interiors, too, are getting a vigorous clean‑up, as though they were relics of a past best forgotten. Old kitchen ranges, once shrines of the family, are being bricked up like mad relations, heirloom furniture replaced by bird-leg contemporary, velvet curtains by surgical plastic, family photographs and daguerreotypes thrown out and burnt in place of china Bambis and celluloid ducks. Some are even taking the bare Cotswold wall, which perhaps had shamed their kitchen for years, covering it with plaster and hanging it with wallpaper made from coloured photographs of a bare Cotswold wall. This quaint improvement, becoming increasingly popular, is known as the Wall Game or As‑You-Were-Only-Better.

Yet in spite of flashier pleasures, and a reasonable restlessness, and the insistent moving‑in of the world, the village remains essentially a village, separate as it ever was. A definite though invisible frontier surrounds it and those outside are not quite of God's choosing. The village and its lore are still the world's centre, the beginning and the end of truth, and everything that comes from outside is rung on the local stones before its genuineness can even be considered. Those who thought that the television and wireless might obliterate identities will find the local accent unaffected.

Children speak it as well as their elders, and it remains untainted save for formal occasions.

Lee in the city: Chelsea Towards the End of the Last War

This is not an anecdote but a memoir of a place and a time – empty Chelsea toward the end of the last war.

I was shaving one morning when the mirror before me suddenly cracked from side to side, at the same time there was a clap of thunder and the sound of some huge roaring vehicle withdrawing in the sky. It was summer, 1944, and the grounds of Chelsea Royal Hospital had that morning been hit by a German rocket.

There were no warnings for they had arrived faster than sound and you heard the bomb explosion first and then the bomber going away.

There was something especially macabre and symbolic about the rockets on London that summer; the tension had gone out of the air raids, there was no waiting now, and people arrived before you knew they were coming.

I lodged in a house in a square just off the King's Road – a quiet residence where the landlord and his wife had often gone to bed when I came home from work at nine o'clock in the evening. The girl who rented the room next door overslept regularly and would go to work naked in the morning, just wearing a mackintosh and carrying a basket of clothes so that she could get dressed later on in the train.

Chelsea was seedy, calm and semi-rustic at that time, with the charm of old paint and large undusted houses. Many had been deserted by their owners and were the haunt of cats and lovers, drunken soldiers on leave, and sometimes all three together.

Chromium, Coca-Cola and cannabis had not yet touched King's Road; in many ways it resembled a provincial high street of last century, full of tea shops, greengrocers and family butchers, though the butchers' windows showed only cardboard cut-outs of sheep. There were also shops selling glass jewellery, billycans, striped utility suits, and sealed jars of chopped carrots and rhubarb.

There were really not many people about at that time: a number of old activists, war artists and camouflage painters, the widows of artists and vivid ex‑models, squeezing out their monthly bottle of gin.

It was the fag end of the war, a quiet conspiratorial time with no secret lives; we were all in it, and by now we knew most things about each other – we shared and stuffed ourselves on them. There was also that all-pervasive sense of eroticism that goes with the boredom of war, that freewheeling fantasising that goes with displaced persons who are displaced through no fault of their own.

The girls and women fell upon the few men with an urgent and hungry disdain. They tidied the rooms of the bachelors and cooked for them. They took our shirts home at weekends and washed them.

For a treat I used to take my girls to the café across the road from The Markham Arms, a long crowded old room of pews and rusty tea cooked in a sort of steam turbine at the end of the room. One ate squares of burnt toast tasting of oil-fired lino, and the scented jam was poured from a bottle. Their bubble and squeak had the bulk and leafy interest of the Gutenberg Bible. Their kippers were the best I've ever known. Was that the last genuine eating house in Chelsea, I wonder, before the whole place began to fall to pizzas?

The Pheasantry was another restaurant, but slightly better class, where you could dine for five shillings.

Imagine Chelsea as it was, with no parked cars in the street. The long mellow vista of terrace houses with their pavements running smooth and uncluttered, and the streets wider and clear to the eye as they were designed to be. The quiet of the country seemed to occupy the area at that time. The square gardens ran slowly and disordered through their seasons without the help of municipal workers.

After sundown there were no lights in streets or houses and the primeval darkness came back to London, a darkness which cleared the sky of its raw, neon-flecked glow and returned the sight of stars and the moon to the city. Flower-seeds blew in and thrived on the bombsites and owls sang in the midnight blue. It was a time of strange peace that the war had given.

'Village Christmas: And Other Notes on the English Year' by Laurie Lee is published on Thursday (Penguin Classics, £9.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks