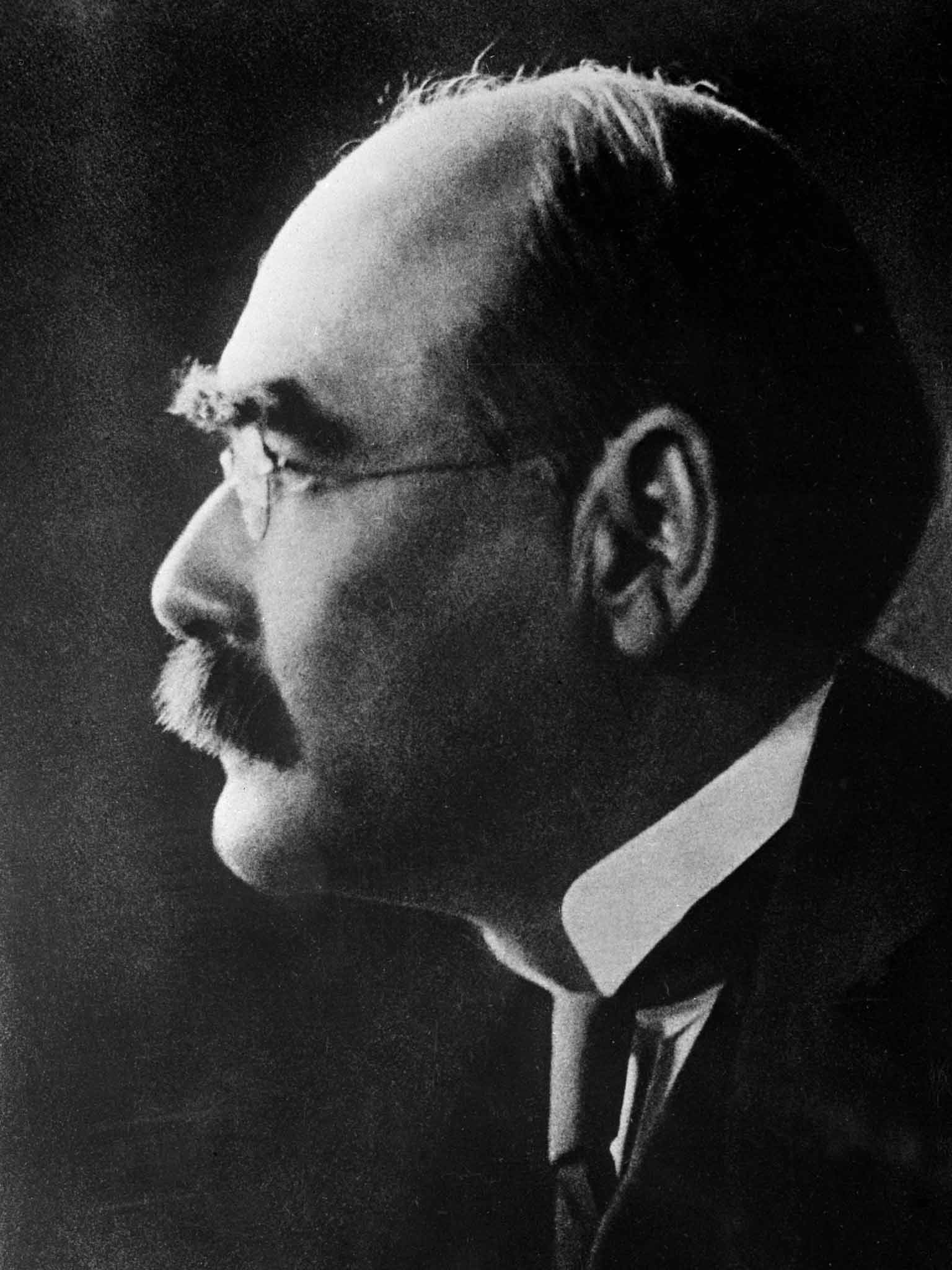

The Jungle Book: A tale as old as time

Two new film versions show the undimmed appeal of Kipling's classic about an Indian boy learning self-reliance from animals

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The link may not be immediately apparent between Baloo the Bear singing "Bare Necessities" in Walt Disney's 1967 animated version of The Jungle Book and Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Discourse on Inequality, published in 1754; but it's there.

You may think the movie a simple, jolly, musical tale of a human "man-cub" hanging out in the wild with protectors – Baloo and a black panther called Bagheera – and trying not to be killed by Kaa the snake and Shere Khan the tiger. But it derives from a work that raised questions stretching back 2,300 years – timeless questions about the relationship between man and the animal world, about nature and society, innocence and corruption.

If you think The Jungle Book a bit old-fashioned, consider that two major new movies based on Rudyard Kipling's stories are currently in the pipeline, starring Hollywood royalty. Filming has just begun on Disney's new, live-action-with-CGI-and-3D version, directed by Jon Favreau and starring Christopher Walken, Bill Murray, Scarlett Johanssen (as Kaa, in case you were wondering), Ben Kingsley, Idris Elba and Lupita Nyong'o. It will be in cinemas in October 2015.

A year later, we'll have the boringly titled Jungle Book: Origins, a motion-capture version directed by the star of mo-cap acting, Andy Serkis. Warner Bros promises that it will be "a darker re-telling of the classic tale". It features the voices of Benedict Cumberbatch, Cate Blanchett, Christian Bale, Serkis himself as Baloo, Peter Mullan, Tom Hollander, Naomie Harris and Eddie Marsan, with Rohan Chand (the only human actor) as Mowgli.

It's not as though we're short of Kipling's tales. Film versions of Jungle Book stories also came out in 1942, 1994, 1997 and 1998. Marvel Comics and DC Comics brought out adaptations in the 1990s. The stories inspired Jungle Book Shonen Mowgli, the Japanese anime, in 1989 and Neil Gaiman's 2009 fantasy novel, The Graveyard Book.

Why the endless appeal? Because it is, to paraphrase a Disney song, a tale as old as time, constantly inspected. Millennia before Wordsworth and Coleridge suggested that "pantheistic" forces in nature – mountains, rivers, flowers, trees – could educate the human spirit, myths had existed about children being raised by animals, outside the conventional decencies of society.

In the 4th century BC, Roman schoolchildren were taught that their city-state was founded by Romulus who, with his brother Remus, was left to die in the River Tiber by their great-uncle Amulius; but that they survived, to be suckled by a she-wolf and fed by a woodpecker, and grew up to be leaders of men and founders of an empire.

It is not clear whether their father was the god Mars, or the demi-god Hercules; whichever it was, the twins' parenting is a potent conflation of gods and jungle creatures, both noble entities, considerably nobler than humans. Romans must have been embarrassed to learn that, once the twins became adult, powerful and competitive, they argued about where to build their city, and Romulus killed his brother. (Just as well, or the capital of Italy would be called Reme.)

Scroll forward 20 centuries and we find Rousseau contemplating the "state of nature", and concluding – in the face of philosophers such as Hobbes – that human "savages" naturally possess "uncorrupted morals", because they are a step up from "brute beasts" and not yet corrupted by the greed and decadence of artificial "civilisation".

Rousseau was credited with inventing the phrase "noble savage" (though it was actually Dryden's coinage); he believed that the human savage was "naturally" and "innately" compassionate about others, possessing empathy and disinclined to see others suffer. Man in his finest state, he believed, was almost identical to an ape; his natural goodness was the goodness of an animal, before it has been "civilised" into duplicity and cruelty.

Darwin's On the Origin of Species (1859) brought the relationship between men and apes into startling focus, by tracing an evolutionary shift from one into the other. It coincided with a mid-Victorian fascination for tales of feral children. Kaori Nagai, the Kipling scholar, unearthed an 1852 pamphlet entitled "An Account of Wolves Nurturing Children in Their Dens", by William Henry Sleeman, a British officer in India. Sleeman writes about several "wolf-children" rescued by Indian villagers: they walked on all fours and ate raw meat; many died shortly after being captured, as though "civilisation" had seized them in its corrupt and bullying embrace, and destroyed their frail purity.

Nagai points out that Kipling (born in 1865 in Bombay) would have encountered many such stories in the 1880s and 1890s. It was his bold creative stroke to make his fictional child not half-animal but wholly human – clever, resourceful and keen to learn the "laws" of the jungle, as distinct from the laws of Western society. Mowgli is seen as occupying a different level of humanity from the "village" society of men-savages: they are superstitious, money-grabbing and homicidal, hardly better, morally, than the chaotic and untameable "Bandar-log" monkey tribe.

Critics have interpreted both villagers and monkeys as Kipling's portrayal of nationalist Indians, ungovernable and subversive – the kind who caused the Mutiny in 1851. Kipling's enthusiastic endorsement of colonialism made him a pariah among 20th-century readers, especially after India became independent in 1947; and the Disney film of The Jungle Book drew accusations of racism, for inventing the character of King Louie, the head orang-utan, who cavorts and swings like the jazz singer and bandleader Cab Calloway while telling Mowgli, "I wanna be like you-hoo". Campus Reform magazine reported in April this year that American university professors hoped that Disney's new film would make amends for the song, because King Louie "is not just a cartoon animal wishing to be human. Rather, Louie represents an African-American stating that he wants to be a member of the white race, which is represented by Mowgli." But, of course, Mowgli isn't white, or indeed British; he's an Indian boy, learning self-reliance from animals.

Kipling wrote the stories at an interesting time in his life. In January 1892, aged 27, he married his beloved Caroline Balestier. The couple went on honeymoon to Caroline's American hometown of Brattleboro, Vermont, to meet the folks. They travelled through the spring but in June, terrible news reached them: the New Oriental Banking Co, where Kipling had invested all his money, had collapsed. Rather than return to England, bankrupt, they set up house in Vermont. Their first daughter, Josephine, was born on 29 December.

Kipling always believed that he was possessed by a djinn, or daemon, which lived in his fountain pen. Now, in winter 1892, as he hunkered down with a new wife and baby, the djinn whispered in his ear about a small boy brought up by wolves in a jungle. "After blocking out the main idea in my head," he wrote in Something Of Myself, "the pen took charge and I watched it begin to write stories about Mowgli and animals, which later grew into the Jungle Books."

The feeling that England was a hostile place must have pitched him back to the England of his childhood. After his first five blissful years amid the sights and sounds, nannies and servants of Bombay, he was sent with his little sister to Southsea, Portsmouth, to live with foster parents, Captain and Mrs Holloway. In the story "Baa Baa, Black Sheep", Kipling describes his six years of mental torture in which he was beaten and humiliated for telling "lies", until he finally threatened to burn down the house. His lost India became an idealised jungle land. Mowgli's ambivalence about leaving the jungle to join the man-village is plainly located in this nightmarish experience.

The Jungle Book was published (with some illustrations by the author's father, John Lockwood Kipling) in 1894 and its sequel, The Second Jungle Book, in 1895. The books spawned a mini-genre of fin de siècle fictions about children of nature, splashing in the shallows of Edenic islands, growing sturdy and beautiful and discovering sudden primal urgencies in their maturing bodies when they meet other children of nature (rather than succumbing to exposure, malnutrition and rickets, being eaten by predators or contracting picturesque tropical diseases). The genre could be construed as a response to the Industrial Revolution, or to reports from the South Seas about partially clad islanders laughing in the sunshine; but the nature-porn books of the 1890s and 1900s were a vivid, post-Jungle-Book trend.

One exponent was the American writer Morgan Robertson, author of Futility, a book about a huge "unsinkable" British ocean-liner called the SS Titan, which, on an April voyage across the Atlantic, hits an iceberg and sinks, killing almost all on board. It was published in 1898, 14 years before the Titanic sank, in April 1912. In 1899, Robertson published Primordial, a novella about a boy who lands on a desert island and becomes a "careless, improvident, petulant child of nature". Robertson didn't share Rousseau's optimism about noble savages. "Children… epitomize in their habits and thoughts the infancy of the human race," he wrote. "Their morals and modesty, as well as their games, are those of paleolithic man, and they are as remorselessly cruel." So we watch the boy learning to hunt, to enjoy killing, and to establish himself as a super-predator.

Robertson clearly influenced Henry de Vere Stacpoole, the prolific Irish writer, ship's doctor and expert on South Pacific islands, who in 1908 published The Blue Lagoon. It tells the story of two young cousins, Richard and Emmeline, who are marooned on a luxurious tropical island after a shipwreck. They build a hut, fish, dive for pearls and explore the island with Crusoe-like resourcefulness. Inevitably, they fall in love and have sex, "an affair absolutely natural, absolutely blameless, and without sin. It was a marriage according to Nature," writes Stacpoole.

Both stories led, in their nature-worshipping way, to Tarzan of the Apes, published in 1912, created by Edgar Rice Burroughs, a Chicago businessman and fan of pulp fiction. His first stories were SF tales of adventurers from Earth finding distant planets – more Jules Verne than Kipling. His Tarzan, however, is a grown-up Mowgli, only posh, British and a superman. He started life as John Clayton, born in equatorial west Africa and adopted by Kala the she-ape after his parents die. Tarzan ("white-skin" in ape-speak) teaches himself to read English, learns to swing through the trees and becomes a great hunter, but also learns to behave in polite society. He is handsome, clever, immensely strong, loyal, decent. He can wrestle gorillas and crocodiles as easily as he can chat to the gentry. He is suspicious of civilisation and its innate hypocrisy – and happiest in a loincloth. He is a triumphant vindication of nature over social nurture.

Rudyard Kipling didn't think much of the Tarzan books. He once said that Burroughs wrote Tarzan of the Apes to "find out how bad a book he could write and get away with it". But he would have appreciated how Burroughs took the eternal questions – how much of an animal is man? What can men learn from animals? – and with them created a world-conquering ubermensch every bit as enduring as his own boy hero, full of animal strength and cunning, and human enough to appreciate it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments