The earliest known Arabic short stories in the world have just been translated into English for the first time

The stories are even more fantastic and full of marvels than those in the ‘Arabian Nights’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Ottoman sultan Selim the Grim – having defeated the Mamluks in two major battles in Syria and Egypt – entered Cairo in 1517.

He celebrated his victory by watching the crucifixion of the last Mamluk sultan at the Zuwayla Gate. Then he presided over the systematic looting of Cairo’s cultural treasures. Among that loot was the content of most of Cairo’s great libraries. Arabic manuscripts were shipped to Istanbul and distributed among the city’s mosques. This is probably how the manuscript of Tales of the Marvellous and News of the Strange ended up in the library of the great mosque of Ayasofya.

There it lay unread and gathering dust, a ragged manuscript that no one even knew existed, until 1933 when Hellmut Ritter, a German orientalist, stumbled across it and translated it into his mother tongue. An Arabic edition was belatedly printed in 1956.

In the 1990s, when I was working on my book The Arabian Nights: A Companion, I came across references to this story collection and, since it sounded very like The Arabian Nights (or, to give it its correct title, The Thousand and One Nights), I thought I ought to have a look at it. The stories in Tales of the Marvellous were indeed as fantastic and exotic as those in the Nights, and I felt as other scholars might feel if they had come across a missing part of The Canterbury Tales or a lost play by Shakespeare.

The stories are very old, more than 1,000 years old, yet most of them are quite new to us. Some years later, I suggested to Malcolm Lyons, the translator of a recent edition of the Nights, that having completed that mighty task, he might consider translating Tales of the Marvellous. He sounded unenthusiastic and I thought no more about it. Then, last summer, he emailed to let me know that he had completed the translation. Now it has been published, meaning these stories can be read in English for the first time.

Although the title page of this medieval Arab story collection has been lost (as have more than half the original stories), the opening sentence of its introduction declares that these are al-hikayat al-‘ajiba wa’l-akhbar al-ghariba, or Tales of the Marvellous and News of the Strange. “Ajiba is an adjective which means ‘marvellous’ or ‘amazing’ and its cognate plural noun, aja’ib, or marvels, is the term used to designate an important genre of medieval Arabic literature that dealt with all things that challenged human understanding, including magic, the realms of the jinn, marvels of the sea, strange fauna and flora, great monuments of the past, automatons, hidden treasures, grotesqueries and uncanny coincidences.

The Qur’an frequently calls on believers to marvel at the wonders of God’s creation, for they are filled with clear signs for “those who will reflect”. And, of course, the Qur’an itself is one of God’s marvels. Extraordinary things were signs of God’s creative power. To marvel at God’s creation was then a pious act.

Several of the stories in Tales of the Marvellous are explicit about the hunger to see or hear about amazing things. The story of Said Son of Hatim al-Bahili begins with the Umayyad Caliph telling his vizier: “I want you to bring me an Arab seafarer who can tell me about the wonders and perils of the sea and do it now. It may be that it will cure my sleeplessness.”

In the third of the four stories devoted to treasure hunting, the leader of the expedition says to the narrator: “I am a man who searches for marvels as you do.” Later, when a centaur tries to bribe the leader not to demand to see the magical crown, he replies: “We only want to look at marvels and to see what we have never seen before, and if we see the crown we can put it back in its place.” In The Story of the King of the two Rivers one of the things that recommends a maidservant to the princess is the servant’s fondness for the unusual.

Tales of the Marvellous includes tales of the supernatural, romances, comedy, Bedouin derring-do and one story dealing in apocalyptic prophecy. The contents page indicates that the complete manuscript contained 42 chapters, of which only 18 chapters containing 26 tales have survived. The handwriting of the manuscript suggests that the copy was made in the 14th century, but its contents indicate that the stories were compiled and in some cases composed in the 10th century in either Syria or Egypt.

This means that the text we have is older than the oldest substantially surviving manuscript of The Thousand and One Nights (from the late 15th century), which Antoine Galland took as the basis for his translation of the Nights in the 18th century. The authors and compilers of both Tales of the Marvellous and The Thousand and One Nights are anonymous.

Not only do the two-story collections resemble one another in the variety of their contents, but they have a handful of stories in common including the intriguingly titled The Story of Abu Muhammad the Idle and the Marvels He Encountered with the Ape As Well As the Marvels of the Seas and Islands. However, the chronological priority of the versions in Tales of the Marvellous is important, since it will provide future researchers with insights into the ways that the compilers of The Thousand and One Nights worked with older materials and elaborated on or condensed what they had before them.

Tales of the Marvellous differs from The Thousand and One Nights in all sorts of odd ways. The author(s) of Tales of the Marvellous had a special devotion for the Prophet’s cousin, Ali ibn Abi Talib, and at the same time respect for the Umayyad caliphs of the 7th and 8th centuries. Several times in Tales of the Marvellous Allah intervenes directly to rescue a hero or heroine in peril. Christian monks feature frequently in Tales of the Marvellous and a historical figure, Muhammad ibn Suleiman, plays a leading role in three of the stories. Why, I do not yet know.

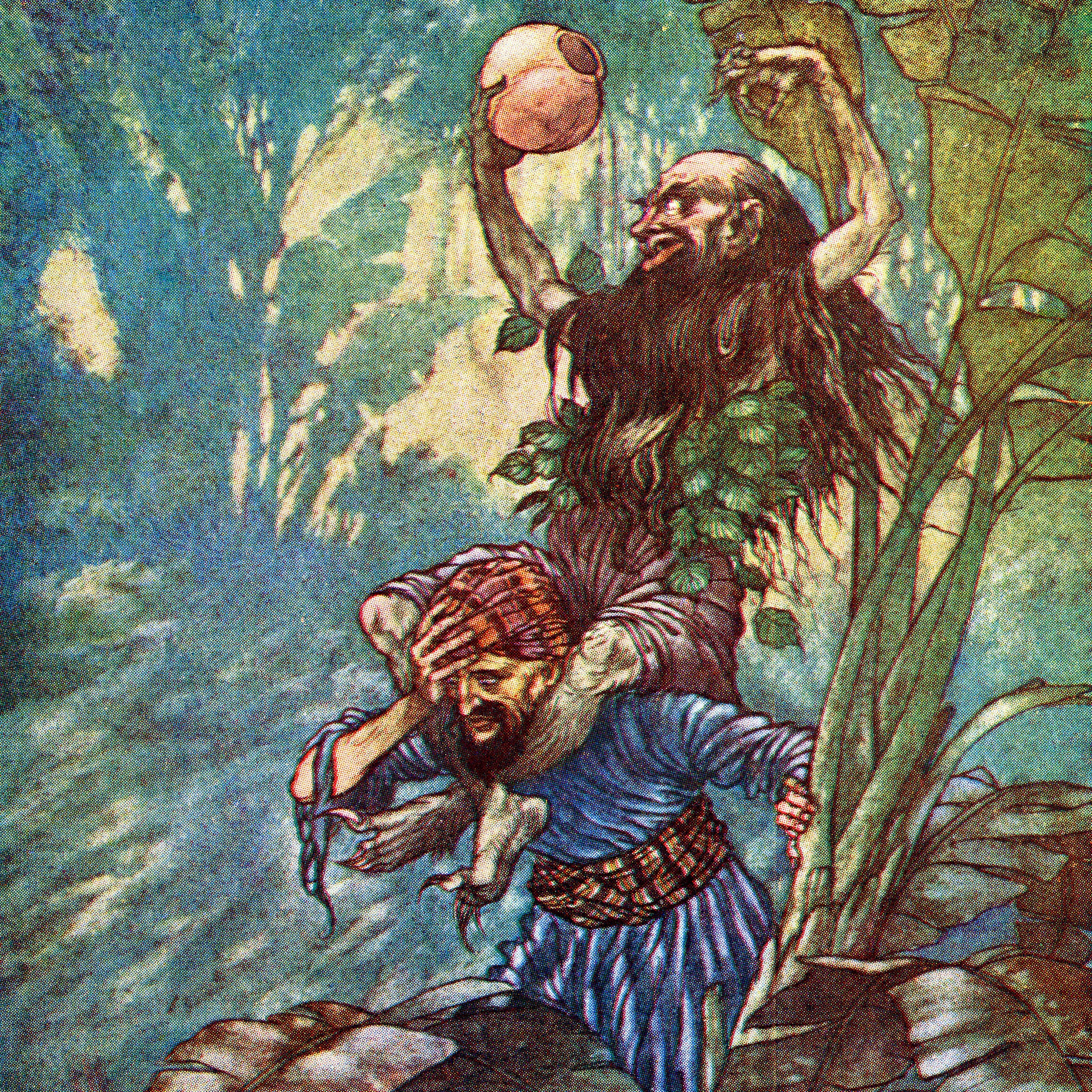

More generally, the fantastic is even wilder and more prominent in Tales of the Marvellous than it is in the Nights. The sheer mad inventiveness of The Story of Mahliya and Mauhub and the White-Footed Gazelle, with its jumbling of Muslim, Christian and pagan beliefs and rituals would take some beating. Here we have a mechanical vulture, visionary dreams, conversation with a pagan god, magical transformations, thrones of wrath and of mercy, an enchanted gazelle, a herder of giant ostriches, lustful jinn, speaking idols, a queen of the crows, a weeping lion, a fortress guarded by talismans, a crocodile with pearls in its ears, the sacrifice of virgins to the Nile and much else.

The narrative is one long carnival of extravagant fantasy. The Story of ‘Arus al-‘Ara’is and Her Deceit, As Well As the Wonders of the Seas and Islands features an Arab Medea who uses poison and sorcery to slay the men and jinn she sleeps with (and she sleeps around a lot). In Said Son of Hatim al-Bahili, a jihadi expedition heads out to India where it encounters not only the armies of the pagan Indians, but also a monk who remembers his times with the Prophet Daniel and with Jesus, but who has since converted to Islam, and he utters many cryptic prophecies. Then the Muslim expeditionary force travels on to lands farther east to discover the Valley of the Ants and the Valley of the Apes.

As I have read and reread these stories, I have slowly become convinced that the person who first wrote them down in the 10th century did not just collect them from other sources, but in some cases he or she actually composed them. Several of the stories show signs of having been driven by inspiration and written down in great haste. For example, in The Story of the Talisman Mountain and Its Marvels, only belatedly does the storyteller remember to bestow a name on the savage mamluk.

The Thousand and One Nights contains one long story about a quest for treasure, The City of Brass, in which the governor of Egypt sends an expedition out to find the sealed copper vessels which contain the jinn captured centuries ago by Solomon. Otherwise, treasure hunting does not really feature in the Nights. But Tales of the Marvellous contains four short stories devoted to treasure hunting and in three of those stories the leaders of those quests are professionals.

The fictional treatment of treasure hunting evolved in parallel with non-fictional treatises devoted to the same subject. In medieval Egypt, professional treasure hunters had set themselves up as a guild. Many of the “professional” treasure hunters were really con men who preyed upon the gullible. Additionally, many treasure-hunting manuals are so full of wondrous accounts of magical spells, death-dealing automata and stories about ill-fated earlier seekers that they should really be reassigned to the category of entertaining fiction.

In fiction, as in purported fact, one needed more than a good map and a shovel in order to unearth ancient treasures, for the treasure hunter might expect to encounter guardian monsters, killer statues and magical traps, and that is indeed what the participants in the quests included in Tales of the Marvellous do encounter. These perilous adventures can be compared to those of Indiana Jones, though the supernatural features more prominently in the medieval stories.

The treasure hunting stories bear witness to the awe experienced by the medieval Arabs when they contemplated the wonders of antiquity and asked themselves what had happened to the wealth of the ancient Greeks and Romans, as well as of the Pharaohs and Persian emperors.

As the stories of dangerous automata suggest, medieval storytellers envisaged advanced technology not as something that would be achieved in the future, but rather as something whose secrets were lost in the distant past. In Tales of the Marvellous, death-dealing automata guarded the treasures sought by the protagonists of the quest stories.

Unusually in The Story of Julnar, the sorceress Queen Lab is mistress of a group of singing automata. Statues were dangerous. In several of the tales in Tales of the Marvellous demons enter the statues and speak through them. Stone monks guard treasure in the first of the four treasure-hunting stories. A statue on the Talisman Mountain has the power to immobilise ships. Such things, neither alive nor dead, are intrinsically uncanny.

Treasure-hunting stories are full of marvels and excitement, but, as with the Nights story The City of Brass, they also carry a lot of moralising about the transience of worldly wealth and the vanity of earthly power. One gets the sense that the treasure hunters are not so much seeking tangible treasures as they are on a quest for adventure and strangeness. The story of a quest for treasure turns out to be the story of the quest for a story.

‘Tales of the Marvellous and News of the Strange’, introduced by Robert Irwin and translated by Malcolm C Lyons (Penguin Classics, £25), is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments