The Crocodile Under the Bed: Judith Kerr's 50-year follow-up to The Tiger Who Came to Tea

Judith Kerr tells Etan Smallman what inspired her latest animal intruder which has taken 46 years to get into print.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

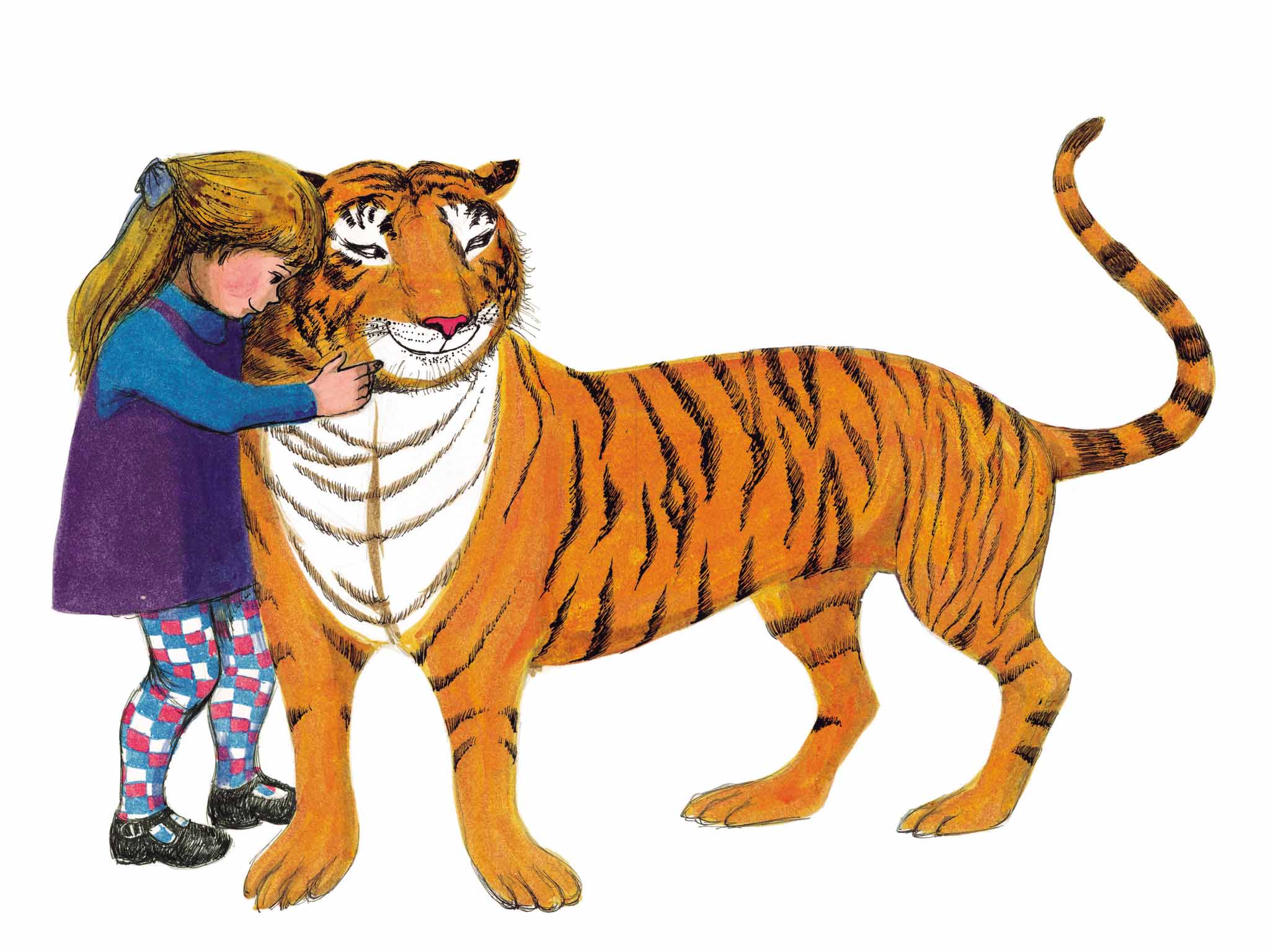

Your support makes all the difference.It is more than 50 years since the tiger first came to tea. Before the much-loved picture book was even written, the story was being told and retold by Judith Kerr to her two-year-old daughter, when they were both at home feeling "a bit lonely".

The 91-year-old is still writing and illustrating, more often than not at the same drawing desk, in the same light-filled study in the attic of her house in Barnes, south-west London, where she has produced everything that she has ever published. But one gets the sense that Kerr – who was widowed in 2006 – would probably be more delighted now than ever to discover a stripey visitor at her front door.

"Since Tom died, I've had nothing else to do," she laments. "I can get up in the morning and I can work and go to bed. I don't cook – I microwave. So I've done quite a lot of books in the last eight years and, of course, it's been the saving of me. Even if you do total rubbish all day, you go to bed and you think, 'Well, I'll fix that tomorrow'."

Her latest title has taken Kerr some 46 years to fix – the result of the perfectionism she inherited from her father, a theatre critic dubbed the "cultural pope" of Germany. Alfred Kerr was also a fierce critic of Adolf Hitler, resulting in him being placed second on the death list drawn up by the Nazis, who were then on the verge of power. His daughter says that he is the only person she has known who not only made corrections after his books had been printed – but after they had been burnt by the Nazis.

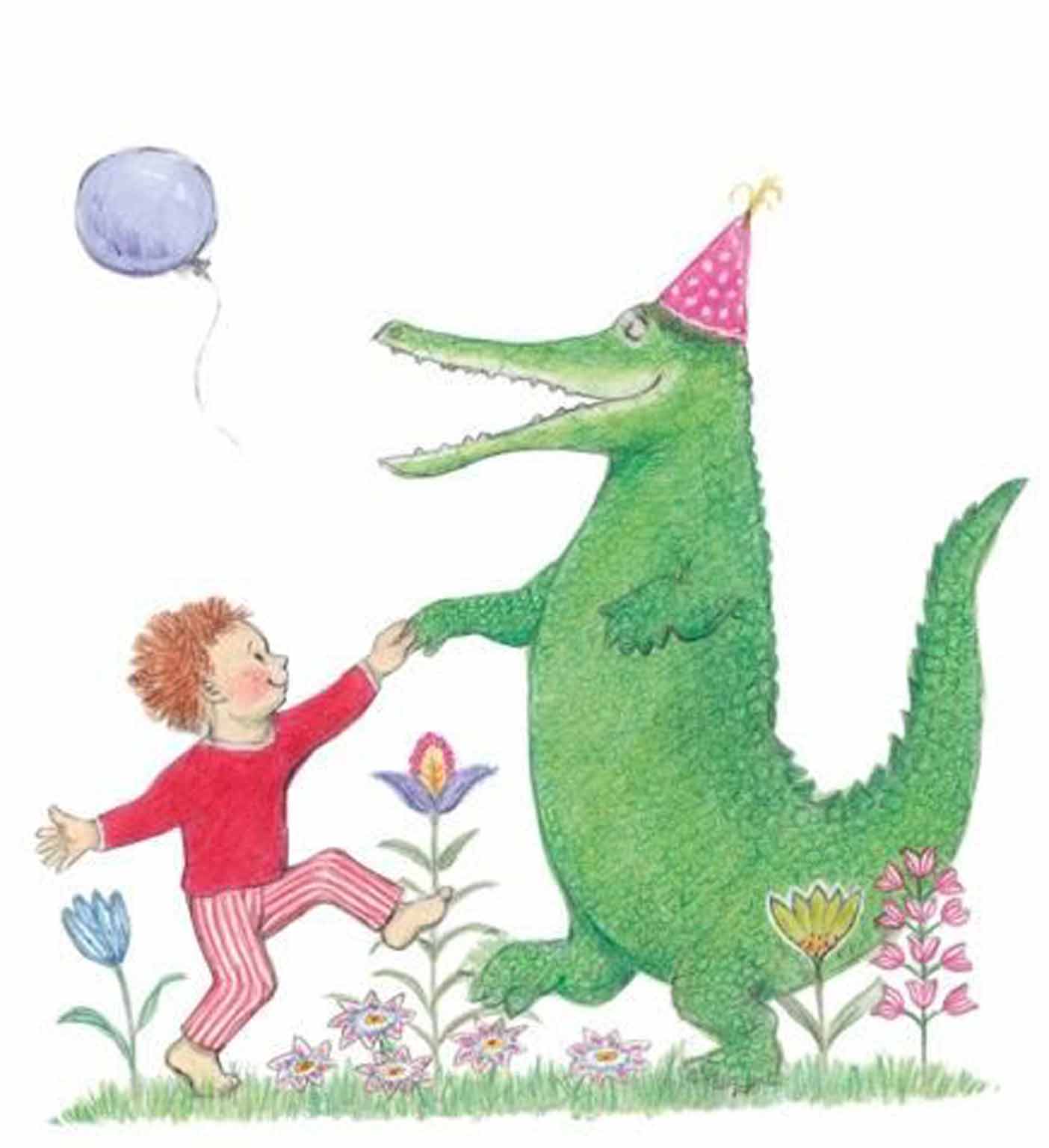

She began work on the original and never-published The Crocodile Under the Bed as soon as Tiger was first printed in October 1968, but reflects: "I don't know how I wrote such a boring book. It was a second book; everybody does a second book that is no good."

Luckily, Kerr's publishers are a patient bunch. When it is released by HarperCollins tomorrow, Crocodile will become her 31st book, retaining only the title and the basic premise from the original concept. Time, however, has not dimmed the author's surrealist touch. The book is as full of the beauty, poetry and whimsy that has graced every piece of work she has created since she started designing wallpaper in the 1940s.

More than that, she insists that she is only now producing her best drawings – and is working faster than ever and with "greater urgency". "For the first time in my life," she says, "I feel that I know what I'm doing." Kerr – immaculately dressed, wearing a yellow blouse, large spectacles and a twinkle in her eye – is modest to a fault.

She is "very slow", she concedes (while she only does one book a year, other illustrators are doing up to four). Even her age, she tells me, is nothing special. "In fact, everybody is in their nineties. I sort of boast about it – I say to people: 'I'm 91, you know'. And they say, 'Oh yes, my nan's 97.'"

Remarkably, for a writer who has sold more than nine million books, Kerr is still conscious of lost time. Her first book was published when she was 45 – and she feels that she still hasn't "caught up".

If she spends more than a moment holding forth – at my behest – on how she would define her style or how she has been inspired by the likes of Rousseau and Chagall, the grandmother of two promptly reins herself in. "This is all becoming rather presumptuous," she says at one point in a gentle, hesitant voice. "They're only picture books." She twice chides herself for being pretentious and characterises the two central themes of her writing – children and animals – as "very soppy".

Of course, for the generations who have grown up with Kerr's creations, they are far more than that. Her children and animals have helped millions of boys and girls to learn to read, all the while furnishing them with images that cannot help but linger – the tiger, head crammed into the sink, drinking "all the water in the tap" (a scene derided by her publisher as "rather unrealistic", which Kerr thought "was odd in view of the rest of the story"); Mog, limbs splayed against the kitchen window, frightening a burglar half to death; Anna recalling how Hitler stole her pink rabbit.

Kerr's energy remains boundless. While reviewing a BBC documentary about her last year, The Independent's TV critic picked up on Kerr's ability to skip up three flights of stairs without pausing for breath – while the presenter, Alan Yentob (aged 66), was left "panting behind her".

Having escaped Nazi Germany aged nine, with her parents and brother, Michael – who would go on to become Britain's first foreign-born judge since the reign of Henry II – Kerr turned to her father and declared: "Isn't it lovely being a refugee!?"

It is a status that continues to define her. "My mother, who was crazy about England, sort of behaved as if she was actually English. But she spoke with a slightly German accent. Once, she said, 'When we won the First World War...'

"Everybody was a bit surprised," says Kerr with a chuckle. "So I don't say 'We'. It's silly, because I've been here, what, nearly 80 years, and I couldn't write in any other language, but it might be assuming something that one's not entitled to, perhaps."

Kerr's family experience also informs her views on the debate over whether to legalise assisted suicide. Her father had a stroke in 1948 and her mother provided the pills with which he ended his life a few weeks later. "Well, I'm all for it," she asserts. "In his case, he wouldn't even have been able to go to Dignitas because it wasn't life-threatening. I would extend it – I mean, Alzheimer's isn't life-threatening and you're supposed to go and be a burden to everybody and put up with this when you know that you're not there. I certainly have a stash of sleeping pills. Most people I know are over 80 and I think we all have, just in case – but, of course, you might not have time to take them. It is a very gloomy conversation..."

Indeed, Kerr has always been loath to agree with those readers who detect an underlying darkness in her work. There is the way she killed off Mog in 2002's Goodbye Mog. Michael Rosen, the former Children's Laureate, picked up on the sinister birds with teeth in Mog in the Dark and, pointing to the tiger, commented: "Judith knows about dangerous people who come to your house and take people away."

Kerr is having none of it. "Well, you wouldn't snuggle the Gestapo, would you?" is her standard riposte. "I'm trying to think if I'm traumatised..." she says haltingly, taking a long pause after I ask if she will admit to there being any pain lurking behind her pictures. "No, I'm just hugely, hugely grateful for what I've had," she decides. "I mean, what more can you want – doing work that you love, a happy marriage, children, in a country at peace for 70 years?"

The only remaining ingredients ensuring Kerr's contentment and longevity are a brisk walk through Barnes Common every evening, a Martini Rosso with lunch and a whisky in the evening. "That's 14 units, that's all right!"

Kerr says of her father that he had "a great talent for happiness". It is another feature that has clearly been passed down.

"But I've had an awful lot of reason to be happy," she concludes. "So I've been happy. He liked the world and I do, too. I get a terrific kick out of just walking about and seeing it all."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments