Tasha Kavanagh on her creepy debut novel Things We Have in Common

A tale of loneliness and teenage obsession which could be the next Gone Girl success story

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Tasha Kavanagh says lots of surprising things as we sit and discuss her debut novel over a cup of tea, but by far the weirdest is when she refers to its “happy ending”.

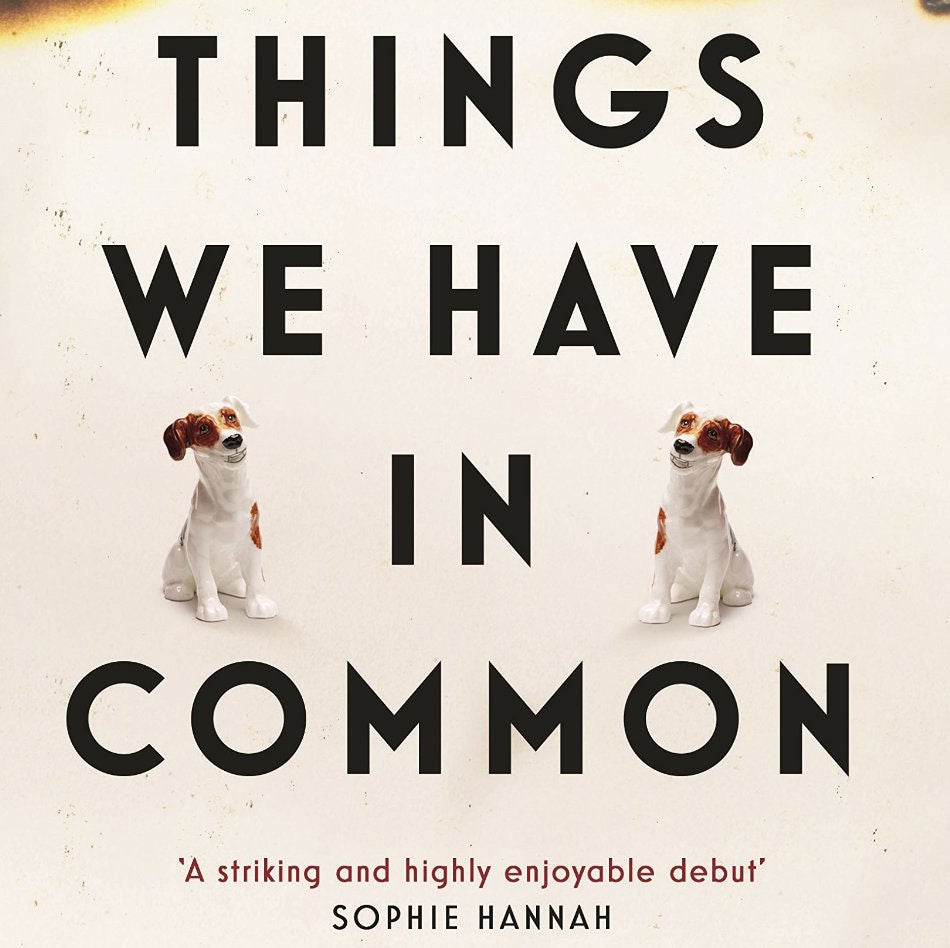

Things We Have in Common is a creepy tale of loneliness and teenage obsession, described by its publisher as “Sue Townsend meets Zoë Heller”, with overtones of Emma Donoghue’s Room. It has the most devastating last line you’ll read all year. So, I do a double-take when she says that for that character, at that moment, the ending is happy and right. “Oh yes,” she laughs, “I think for me it was always going there.”

Things We Have in Common is narrated in the second person by Yasmin: 15, overweight, obsessive, a “freak”. Yasmin has latched on to the pretty girl at school – follows her around, even collects her discarded belongings in a special box – and soon she latches on to a man she sees watching Alice. “[If you killed me] it’d actually be a bonus, a double bonus even, because if you did and then got caught because of it, I’d have saved Alice by sacrificing myself...” recounts Yasmin as she becomes ever more wrapped up with “you”, “the man”, convincing herself that he is going to “take Alice”. She even persuades herself that “you” will her friend. And then, Alice goes missing...

The whole plot of the novel, its title and its beginning came to Kavanagh when she started thinking about “using ‘you’ as a way in”, she says. “The moment I wrote the first line I saw her standing in the field, I saw Alice, I saw the man. And from that moment I just saw the connection, this really romantic connection between these two lonely people.” By “lonely people”, she means a 15-year-old fantasist and a man who may turn out was weird.

Kavanagh is already the author of nine picture books for children under her maiden name, Tasha Pym. (Have You Ever Seen a Sneep also has a second-person register, she points out, but that’s where the similarity ends.) She followed an unusual route into writing. She sailed for the British youth team as a child, taking part in her first championship when she was 12, and she remembers training intensely with her Olympian father.

“After school, in the dark. No words, just my dad’s elbow on top of me ... and I just had this really intensive training in how every millimetre counts and how to sail the boat on a knife edge...” She refers to it again later, when she talks about Yasmin: “She’s just going towards what she needs, never stops, just keeps going, walking towards it. And she just can’t give it up because that’s everything. I think that thing with her holding Alice’s belongings, and the whispering, it’s sort of getting herself into a catatonic state. And I very much felt like that when I was sailing.”

She tried to reproduce that state while she was writing the novel, she says, by spending hours on eBay. “It gets you into a perfect state of catatonia,” she insists, quite seriously. “Dumbs you down till you’re just this kind of drone, and the work would come out of me.” It was one way of convincing herself that she could write a story of more than 300 words, and there was no editing; her first draft was the finished novel.

After getting into writing during a creative arts degree at Trent Poly, Kavanagh went straight into the University of East Anglia’s prestigious creative writing course, where she was taught by the likes of Malcolm Bradbury, Rose Tremain, and Michèle Roberts. “I was on a course with people who’d come from the other side of the world, and they’d given up a year with their families to be there. And I was like, ‘Oh, right! This is serious!’.” But from there, she went into film-editing, working on big movies such as Twelve Monkeys, Seven Years in Tibet and The Talented Mr Ripley.

“I was immediately drawn to editing, because it’s that same kind of very precise, private, quiet work. And the sense that you could create many stories out of the same material, depending on where you cut.” She apparently had a knack for editing the lip syncs, and I wonder if it gave her an ear for dialogue. Not so much that, she says, as a connection with char-acter. “You’ve almost got to feel the words into the lips. There was that definite feeling of connection with the character and what they’re saying.” It had an added bonus: when she was editing The Talented Mr Ripley she was pregnant with her daughter, who for weeks after her birth could always be put to sleep by Matt Damon’s voice.

It was Yasmin’s voice that first drew me to the novel. A short extract, copied out by a publicist in her best teenage handwriting, and sent out with early review copies, just reeks of teenage insecurities. Kavanagh says that she loves reading about teenagers, and mentions Go Ask Alice and John Fowles’s The Collector as books that subconsciously inspired this novel. It is very much a novel for adults, but teen-agers will love it, I’m sure. “I just think it’s the most powerful time of your life. That’s how I remember being 15: extremely intense, powerful, alienating, and full of contradictions. I think it’s those juxtapositions that make for a really exciting story.”

She adds: “One thing I found interesting [when] writing it is how easy it is for someone to just slip through the net of society and for that to go unnoticed. And, if somebody is quite unappealing... To be honest, if I met Yasmin I don’t think I would want to be her friend. And that’s kind of the point: that my response to her and everybody else’s response to her, from our perspective, is just fleeting, but from her perspective, it’s all she gets ... there’s a responsibility there that I hope the reader will feel.”

Things We Have in Common is the first in a two-book deal for Kavanagh, and I can see it having the word-of-mouth success of a We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves, or even a Gone Girl. The next novel comes from a similar place, she says: “dark, psycho-logical”. She adds, almost as an afterthought, “I’m always drawn to the dark.” Fans – and there will soon be many – had better brace themselves for some more chillingly happy endings.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments