Stanley Spencer's daughter, Unity, on life amid the most bizarre domestic soap opera in British art history

Unity has written a jaw-dropping book about her life - repressive families, depression, conmen lovers and all

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Lucky to be an Artist is the title of an autobiographical book by Unity Spencer, 84, daughter of the great painter Stanley Spencer. Lucky? Hers is a story tinged with such sadness that it could hardly be described as such. “Children of geniuses tend to have a rather hard time of it,” she writes with a wry directness which informs her whole book – part diary, part stream of consciousness. Indeed the legacy of being a Spencer has apparently not had a positive effect on her own son, John, 51, who reveals with offhand matter-of-factness: “It is miserable, just awful, being Stanley’s grandson.”

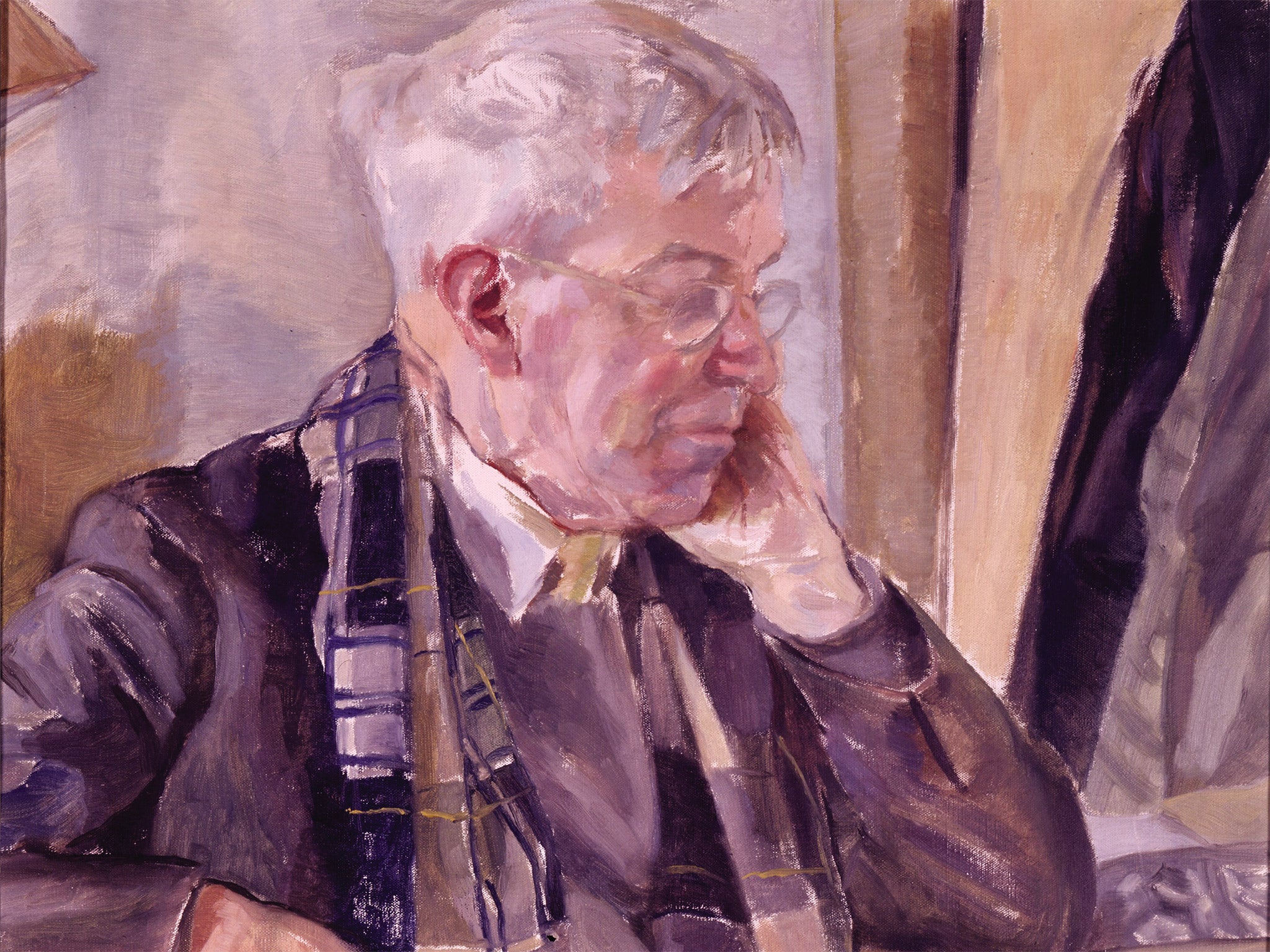

We are at the Fine Art Society Gallery in London, where Unity is having her first major exhibition. Her paintings and prints hang alongside those of her famous father and her mother Hilda Carline, another talented artist, as well as works by her uncle Richard Carline. John ushers me round, pointing to one of the paintings and saying: “That’s my miserable bastard of a dad”. He introduces me to Unity, who is eating her lunch in a back room at the gallery with her elder sister, Shirin.

Having met the Spencer sisters I can confirm what the newsreader Jon Snow says of them in the introduction to Unity’s book: “Now in their eighties they remain the most gorgeous sisters – beautiful, funny and with a wonderfully vivid account of what growing up with one of the more eccentric British artists was really like.”

By Unity’s account there was forgivable eccentricity, yes, but worrying instability too. Their parents split up following what has been described as “the most bizarre domestic soap opera in the history of British art”: Stanley formed an obsessive relationship with another Cookham-based artist called Patricia Preece, whom you might recognise as the nude from Spencer’s “Leg of mutton nude”. Only Preece was a lesbian, living secretly (it was the 1930s) with her long-term lover, a talented artist called Dorothy Hepworth whose work Preece used to pass off as her own. About a week after his divorce from Hilda they married – and Preece went off on their honeymoon with Hepworth while he stayed in Cookham to finish a painting.

“I think Patricia fascinated and flattered Daddy,” Unity writes. “And, although he made light of it, I believe he fell down heavily because of her flattery. I think he was naive more than innocent: he was no longer sexually innocent because he’d been with Mummy [he was a virgin when they met], but he was naive about Patricia. I don’t think he knew much about lesbians – very few people did at that time.”

Even before their parents separated, the pressure of Stanley’s genius and her mother’s bouts of depression had created an unusually detached family setup. When Unity was born, Shirin, five years older, was removed from the family house and sent to live with the mother of one of their aunts through marriage, Mrs Harter. She would never return to live with her parents and, after war broke out, Unity too was sent to live in Epsom with the elderly sort-of-relative whom the girls called Minnehaha.

“It wasn’t necessarily safer but Mrs Harter was able to look after us,” Unity says. “She had a bit of a down on me, really. I don’t know why. She was inclined to put one person on a pedestal and she did that with my sister.” She writes of feeling her sister had entered a “sort of conspiracy against me with Mrs Harter”, whom she describes as a very controlling Victorian person, apparently intent on keeping the sisters and influencing them against their mother. “It wasn’t good. Shirin and I get on fine now, but it has not been easy,” Unity says.

During her early years Unity’s father is presented as a remote but loving figure. Stanley wasn’t around much in the three or four years after her parents’ separation but she must have seen him as he painted a rather remarkable portrait of her when she was seven. As a teenager and in her twenties Unity used to stay with him in Cookham and he encouraged her artistic talents. Several of her letters to him are included in the book and they reveal a close bond as well as Unity’s burgeoning talents – her letters are littered with illustrations and she seems to find sketching as natural as writing.

The to-ing and fro-ing between her mother in Hampstead, her boarding school, Mrs Harter in Epsom and her father in Cookham, trying to fit in everywhere, would inform a lifetime of repression which only decades of therapy could later undo. When she was 20 her mother died of cancer and Unity went to live with relatives who, although kind enough, didn’t take much interest and left her largely alone. She decided not to speak unless she was spoken to, which she said they never noticed.

Stanley, who had remained good friends with Hilda despite their divorce, was there when she died. “Daddy went and sat with her right up until she died, thank goodness. I was too late. It was awful, just awful. I howled all over the hospital,” Unity says. “It was difficult for me because I had just started at the Slade and this was all rather exciting and I don’t think I could face up to the fact that my mother was dying.”

Unity experienced her “first serious bout of depression” in her late twenties, and when she was 29 Stanley died too. “My father seemed to me such an incredible person that to state all the wonderful and beautiful things about him would belittle them,” she writes. Orphaned at nearly 30, and suddenly free of the pressure to make her parents happy, Unity experienced something akin to adolescent rebellion, leading to her first sexual relationship and a pregnancy outside marriage – still a taboo in the early 1960s.

What a shame it was, I suggest, that the child she had, John, hadn’t met either of his grandparents. “They would have loved him, and he them,” Unity says, staring at me apparently with great sadness. “But if Daddy had been alive I would never have got involved with John’s father. All very odd.”

She met Leslie Lambert, John’s father, who was 20 years her senior, two years after Stanley’s death. “He seemed to me an honest working-class man, warm-hearted and idealistic – a Communist, Marxist-Leninist,” she writes. But the relationship would go on to “blight” Unity’s life for a decade as Les became increasingly unstable. He once told Shirin that Unity “could have John until he’s seven months old. After that he’s mine.”

Unity believes that Les’s abusive behaviour towards her once she became pregnant was intended to send her mad in a scenario redolent of the film Gaslight. “He wanted me to become mad and then he thought he could have John forever but of course it wouldn’t have worked like that. They would’ve investigated his state of health. He seemed to think he was fine, but he wasn’t. An absolutely dreadful man. Horrid. A conman. Conned everybody. I think my aunt Nancy was the only one who wasn’t conned. She said he was completely mad.”

Les ended up living in his caravan, driving about and following Unity and turning up at her Cookham house in the middle of the night. In 1969 John was made a ward of court as the legal battle over custody continued and Unity took her son into “exile” in an attic bedsit in London. The unresolved dispute ended two years later when Leslie died of a heart attack. John is more sanguine about the father who died when he was just seven. “He was inadequate,” he says. “But I doubt he was truly evil or nasty.”

Unity’s book describes years of loneliness and unhappiness – even the struggle with painting, for which she lost all enjoyment. But she found contentment in her later years, admitting she was freed by a decision not to paint in oils, instead making lithography and etching. One of her latest works, an etch of a scrotum, which she titled “Dangly Bits” (which causes John to burst into laughter), is a sign of her sense of humour. Her life did not become truly happy until she turned 70, when she stood in front of a group of people after years of therapy and said: “I refuse to be the victim.” And at 84 she’s having a whale of a time.

‘Unity Spencer: Lucky to be an Artist’ is published by Unicorn Press; the exhibition at the Fine Art Society, London W1, runs until 17 April (020 7629 5116)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments