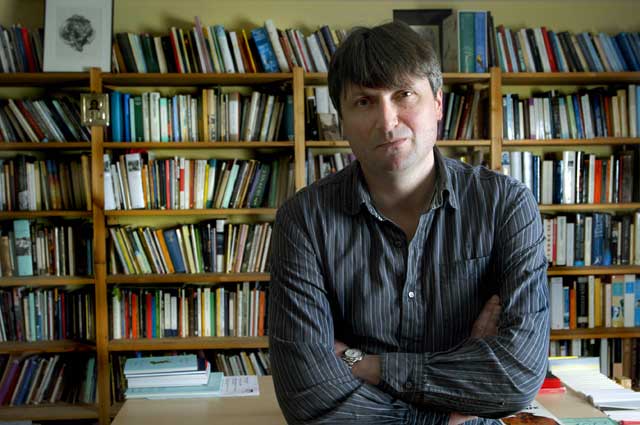

Simon Armitage: 'I'm quite boyish in my outlook'

Simon Armitage, renowned writer, national curriculum fixture, is that rare thing: a poet who admits to a sunny frame of mind

There was a time when poetry was hailed as "the new rock'n'roll" and Simon Armitage was claimed as its star. It was marketing nonsense, of course. Poetry is, as it has always been, a passion that runs as deep as the human soul, one that costs little, and everything, one that can be as bad, or good, fashionable, or unfashionable, profound or superficial as any other art form, but mostly one that, out of the limelight, and away from the glare of the media, or the big prizes, or the big money, plods quietly on.

But that doesn't mean that Simon Armitage isn't a star, or that he wasn't one of a handful of poets who showed that poetry could be both intelligent and popular, both timeless and contemporary, both streetwise and wise – and not just one of them, but one of the very best. When he first burst onto the poetry scene, with his Bloodaxe collection, Zoom!, the probation officer from Oldham had a spiky haircut, an earring and a leather jacket. Twenty years on, published by Faber, a fixture of the school curriculum, close runner for the laureate, poet-in-residence at the South Bank, and stalwart of the BBC, he still has an earring, and he still has a leather jacket, and he still looks extremely boyish. The spiky hair is no longer spiky, but the voice is still pure Huddersfield – both gentle and laconic – and the man is, too.

"Huddersfield is not New York," he says, "and it's not the prettiest town in the world, but it's manageable. It's got everything I need." He has just picked me up from the station and driven me through gorgeous countryside to an old school on a hillside, one which makes me think of Jane Eyre's Lowood, but which, it turns out, has been converted into extremely swanky apartments and, in his case, houses. At the foot of his lawn are the Pennines but here, inside, there are big squashy sofas, and books, and photos of his wife, the radio producer Sue Roberts, and his 10-year-old daughter, Emmeline, and a handwritten poem, in a frame, by Seamus Heaney and a bottle, from Ted Hughes, of laureate wine. It's smart and cosy and domestic and grown-up. Only the guitars, propped up against the walls, hint at another life, the life of a first-time 40-something rock musician. Of which, more later.

"I like the sense here," he continues, "that language has been handed on, and ideas have been handed on." Which is, I'm sure, true, but it's also true that Simon Armitage, who grew up just outside Huddersfield has, apart from his time as a geography student in Portsmouth, and a six-month teaching stint in Massachusetts, never even thought of moving away. Like Ted Hughes, whose poetry he read as a teenager – an experience which changed his life – he is Yorkshire born and bred and has Yorkshire in his soul. The North is a central theme in his work, and the subject of a touching, funny, and, yes, laconic memoir, All Points North.

It's also a theme in his magnificent translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight – hailed by one reviewer as "the best translation of any poem I've ever seen" – and in Gig, the memoir he published last year about his life-long passion for rock music, his "gigs" as a poet and his own attempt, age 44, to start a rock band. It's a wonderful book: warm, engaging, and so funny that it literally had me crying with laughter. What's very clear, however, is that the boy who, as a teenager, fell in love with punk – practically worshipped The Fall – never had much of a rebellion of his own. In All Points North, he describes an exercise in which he and his fellow trainee probation officers were invited to demonstrate the important people in their lives by using buttons. Armitage picked four – one for his father, one for his mother, one for his sister and one for himself – in a neat arrangement, and was surprised by his fellow students' wild, non-nuclear diagrams. "I just thought of that as a kind of normality from which everybody else had deviated," he says, "perhaps through no fault of their own."

Thirty years on from that adolescent love affair with punk, which has never faded, Armitage has his own nuclear constellation of buttons and still lives round the corner from his parents. His father, in particular, is a gargantuan figure in his work. A retired probation officer (yes, Armitage followed in his father's footsteps), one, indeed, who claimed to be slightly "pissed off" that his son managed to retire before he did, he's a lynchpin of the local am-dram scene. "He's massively extrovert, my dad," says Armitage. "He's a very big character locally, and I will, for as long as I live here, always be Peter's son." So does that mean that the man who has now been studied by four million teenagers on the school curriculum, who pretty much everyone thought would follow in Hughes's steps as laureate, and who's often stopped on trains as "that bloke off the telly", can't get too big for his boots?

Armitage puts down his mug and smiles. "There's that phrase round here about 'coming it'," he says. "It means you can't pretend you're somebody else. On Saturday my mum asked me if I'd open the village Christmas fair back in the parochial hall in Marsden and it was the hardest gig of the year, because I couldn't come it. I have always," he adds, "been in my head a kind of son. I think I'm quite boyish in my attitude and outlook. I used to think that was just to do with the fact that when I started writing I was young in relation to the poetry scene, but I'm not any more, so I started to think of it as not a state of mind, but a personality type."

This, presumably, is why Armitage agreed, when his college mate Craig suggested it a couple of years ago, to pursue their youthful dream of starting a band. The Scaremongers (as they eventually decided to call themselves, and not Midlife Crisis, as his father suggested) have recorded an album and performed at Latitude and on The Culture Show. They're not at all bad, actually, but Armitage, who is used to winning plaudits in practically everything he does (not just poetry, but also fiction, memoir, theatre, libretti and telly) is touchingly clear that this is about friendship, "getting off our backsides and doing something instead of just blabbing about it" and making a record, so that he and Craig can "die happy".

What it isn't, clearly, is the fulfilment of a fierce ambition that has haunted him. "No," says Armitage firmly, "it couldn't have been. Otherwise, I think I would have tried it." Indeed. When he discovered poetry as a teenager (Hughes, Larkin, Plath, Heaney, Thom Gunn) it was, he says, like finding "little acts of magic on the page" that he couldn't talk about with anyone else. He started writing poetry on the quiet, but it was only in his early 20s, after going to a poetry workshop in Huddersfield run by Peter Sansom, that it really began to take off. Zoom! was published in 1989, and hailed for its "erudition", "moving originality" and "nouse". In 1992, he was part of the New Generation poetry promotion which, if it didn't exactly establish that poetry was the new rock'n'roll, certainly showed that it could be blazingly alive. In that year, too, his second poetry collection, Kid, was published by Faber. He gave up his day job and has earned much more from his poetry than he ever did as a probation officer.

He has published 11 collections, two highly acclaimed novels, two wonderful memoirs (there's another one, about a walk through the Pennines on the way), three plays, a new version of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and is now working on a new version of Le Morte d'Arthur. He has written poems for festivals, anniversaries, companies and the Millennium. He is working with the South Bank on a poetry Parnassus for the Olympics, and has just written a new introduction and "postlude" to Peter and the Wolf. He has acquired a literary education along the way, and a dramatic education, and a musical education – and, almost irritatingly, he does it all brilliantly. Success, for a poet, just doesn't come bigger. Except that he didn't get the laureateship.

"I tried," he says, when I try to ask him if he cared, "to keep utterly out of it when it was all going on. It was like all this sort of thunder that was getting nearer, and I kept thinking, 'am I going to be struck by lightning?' and then it sort of passed over. I think," he says with disarming honesty, "if they'd offered it, I might have taken it, but probably for the wrong reasons. I think I would have been flattered, but actually it would have been a massive distraction. You know me, Christina, do you think I'm ready to take on the poetic responsibility of 60 million people? Because I don't."

Actually, I tell him, I do, but I think that Carol Ann Duffy will be, and already is, a wonderful laureate, and I also think that none of it matters, because it's all about the poetry. Deep in his heart, I think he thinks this too. There's a wonderful description in All Points North of writing as "a form of disappearance", "a drift away from the apparent and the appreciable into a state of breath". There isn't, he says, "another human activity which combines stillness and silence with so much energy".

He has talked elsewhere of poetry as a kind of healing. Twenty years ago, he was told he had ankylosing spondylitis, a condition in which the vertebrae can fuse and cause curvature of the spine. He had to give up sport and still suffers bouts of periodic pain. But he still walks tall, and is still super-productive and was told, on his last check-up, that the "nomenclature" of his condition had changed. "There was a time" he says "when I decided that I am not going to have this." Word made flesh. Word renaming flesh. It's a wonderful symbolism, we agree.

In Gig, at a gig, a Morrissey gig, in fact, Armitage confesses that he is "a person whose mood indicator rarely swings below the contentment line", a phenomenon which is, let me tell you, pretty rare in a poet. "I exist on a fairly happy surface level," he says, "but when I'm on my own, and I'm doing the writing, I do drift to those darker places." Talking to him now – this level-headed, modest, brilliant and thoroughly decent man – it's hard to imagine, but it's there in the poetry, of course. "I think," he says, "the more time that you spend considering the issues out of which your writing will come, the inescapable fact that at some point you will die becomes clearer and clearer. And that's at the bottom of the well. It's also the one thing that unites us all."

'Peter and the Wolf' with the Philharmonia Orchestra is at the Royal Festival Hall from 28-30 December (Southbankcentre.co.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks