Sheila Rowbotham: 'Alice Wheeldon, a false accusation, and why the case still matters'

Rowbotham wrote her play 'Friends of Alice Wheeldon' after reading an account of the case in Raymond Challinor's The Origins of British Bolshevism

In December 1916, an intelligence agent, William Rickard, pretending to be a conscientious objector and using the pseudonym "Alex Gordon", arrived at the door of the Derby socialist and feminist, Alice Wheeldon. Giving him shelter that night would have devastating consequences for herself and her family.

After staying with Wheeldon, he claimed to have uncovered a plot to kill not only the prime minister, Lloyd George, but the Labour leader in the coalition government, Arthur Henderson.

Alice Wheeldon kept a second-hand clothes shop, had been a member of the Women's Social and Political Union, and was on the Left in the local Independent Labour Party. But World War One divided feminists and socialists alike. Like Alice, her four grown up children Nellie, William, Hettie and Winnie opposed the war, making them part of an ostracised but resilient minority. William was a conscientious objector, and Hettie, a school teacher, was the secretary of the local No Conscription Fellowship which defended the rights of men who refused to fight.

The space for such rights wore thin amid the panics about security which accompanied the horrific loss of life in the war. Small competing intelligence agencies mushroomed, searching for German spies and keeping many left-wingers, pacifists and feminists under surveillance.

Alex Gordon, a somewhat bizarre representative of law and order, was from a group called PMS 2, attached to the Ministry of Munitions. When Basil Thomson at Special Branch, a zealous hunter of red subversives, checked Gordon's finger prints, he discovered a criminal record, false identities and a history of mental instability.

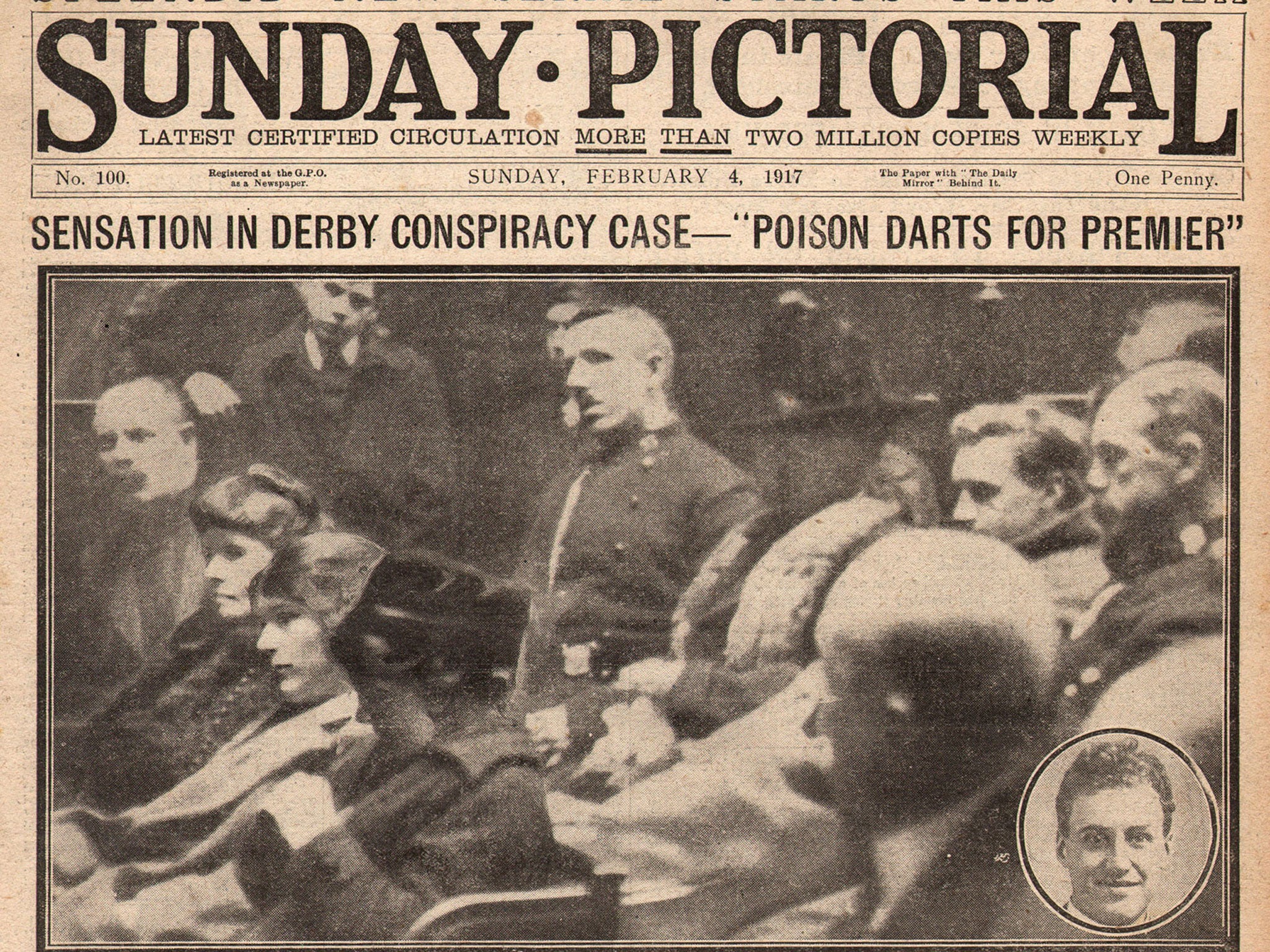

Nevertheless the post of Alice, Hettie, Winnie and her husband, Alf Mason, was searched and phials of poison found. All four were charged with conspiring to assassinate Lloyd George by firing an arrow at him. The prosecution at the trial was led by the Attorney General, the brilliant right- wing lawyer, FE Smith. Though Alice insisted she was told the poison was for dogs guarding men in an internment camp, Smith's caricature of the accused as both demented subversives and dissolute women, corrupted by wild suffrage militancy, swayed both the press and the jury. All but Hettie were found guilty and sentenced to hard labour.

In prison, Alice went on hunger strike, protesting her innocence. An amnesty would eventually release all the accused, but the damage to their lives was irrevocable. They lost their livelihoods and were scarred by the scandal and fear the case aroused. Alice Wheeldon died during the influenza epidemic in 1919.

When I read a brief account of the case in Raymond Challinor's The Origins of British Bolshevism (1977), the stark drama of the state shattering lives remote from the powerful moved me to write a play, Friends of Alice Wheeldon. In 1980, it was performed in pubs and theatres in the North and in London. I followed this up with a long contextual preamble, "Rebel Networks in the First World War", published with the play, in 1986. I was, and still am, fascinated by elusive dissident networks.

I was influenced by radical historians in the 1960s who sought to make the hidden visible and the silenced heard, and, when we started the women's liberation movement in 1969, some of us began to rethink suffrage history from the bottom up, uncovering the intricate connections between suffrage campaigners and participants in other movements for radical change. This was the kind of milieu in which Alice Wheeldon was rooted.

Historians, like journalists, are apt to focus on moments when people surface and not track what follows. However, the Wheeldons and Masons never quite went away and startling new information kept coming to light. For example I had followed a false trail on the fate of William Wheeldon; Nicholas Hiley, a specialist in the history of intelligence, discovered he had been executed in the Soviet Union in 1937.

Alice's great, great granddaughter Chloe Mason and her sister, Deirdre, have been collecting evidence to present to the Criminal Cases Review Board. Those convicted in that dubious trial certainly deserve better from British justice.

I hope the new edition of my book will add to interest in the case. The Englands that collided then are still at variance. Injustice to those without wealth and power persists, the state still covers up its own wrong doings, and the sneering contempt FE Smith displayed towards defiant women is still abroad. We need those rebel networks.

'Friends of Alice Wheeldon' by Sheila Rowbotham (Pluto Press, £14.99) is republished on Monday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks