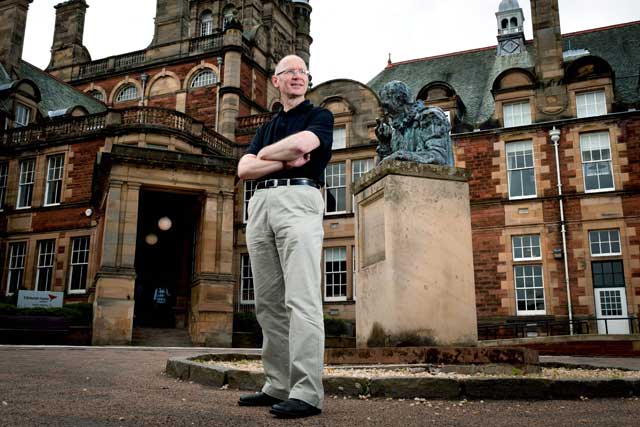

Scots guard: James Robertson has dedicated himself to preserving the native culture and language north of the border

The doyen of the Scottish literary scene steers Doug Johnstone through his dizzying new grand opus, tracing half a century of life north of the border

Sometimes you can just tell when an author has taken a big step up in ambition. Whether it's the sheer heft of the new novel, or the structure, the premise or the prose, books occasionally come with an aura about them – a quality that quietly states: "This is the big one."

That feeling is inescapable when reading And the Land Lay Still, the fourth novel by the Scottish writer James Robertson. For 20 years, after beginning his career with short stories and poetry in both English and Scots at the beginning of the 1990s, the unassuming author has been there or thereabouts on the Scottish literary scene. He's carved out a place for himself as an important figure in the country's burgeoning creative self-belief, establishing a small poetry pamphlet press called Kettillonia, and Itchy Coo, an extremely successful publisher of children's books in the Scots language; as well as holding a number of high-profile posts, most notably the first writer-in-residence of the Scottish parliament.

At the same time, Robertson has also made a name for himself as a brilliant and thoughtful novelist. His first two novels, The Fanatic and Joseph Knight, were precise works of literary and historical insight, and both won major prizes north of the border. In 2006, Robertson published The Testament of Gideon Mack, a subtle, modern reworking of two Scottish classics: Robert Louis Stevenson's The Strange Case of Dr Jeykll and Mr Hyde and James Hogg's The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner.

The book was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize but, more importantly in terms of profile and sales, it was picked for the Richard and Judy book list, cementing Robertson's reputation as one of the handful of writers able to straddle the chasm between literary worth and mainstream success.

And so, four years later, we have the follow-up. And the Land Lay Still is an epic undertaking; a 670-page whopper that tackles the political, cultural and emotional undercurrents of the Scottish nation from the early 1950s to the present day. Split into six parts and featuring a dizzying spread of narratives, it nevertheless coheres into a powerful whole, reading almost like an alternative history of the country told by its everyday people instead of its movers and shakers.

"I'm very excited but also a little nervous about it coming out," Robertson admits. "I've invested all this thought and energy and time into it; it's certainly ambitious in terms of scope. As well as excitement, there's also a sense of relief. I'm glad I got it done because there were moments when I wondered what I'd taken on. I didn't consciously say, 'Right, I'm going to do the big one now,' but I always had that at the back of my mind."

We're chatting in Robertson's office at Edinburgh Napier University, where he's currently writer-in-residence. The Craighouse campus is a beautiful sprawl of Victorian buildings, but Robertson's office is a rather more prosaic chipboard-and-whitewash affair. He looks fit and happy, younger than his 52 years, and his voice rises steeply in pitch whenever he gets excited, which is quite often, especially when talking about the new novel.

Despite its myriad storylines, And the Land Lay Still is, like all Robertson's work, eminently readable. Part of that is down to the novel's clever structure. In the opening section, we meet Michael Pendreich, a middle-aged man attempting to curate an exhibition of photographs by his late, famous father Angus. The latter's huge body of work spans the half-century from the Second World War on, and Michael is struggling to enforce any kind of order on it.

In an early conversation with a friend, the two throw around ideas about imposing narrative on events, something that's key to the whole novel. At one point the friend says: "A story is a whole mass of details that come together and form a narrative. Without that coming together they're just a lot of wee pieces. So what happens if you take a story and break it into its wee pieces? When you put it back together again, will it turn out the same way?"

"That conversation was an important part of writing the book," says Robertson. "I needed to get my head round what it is that happens when you force diverse events into a story. Of course, looking at this big, 670-page book, it's an artificial construct. Stories are what I do for a living, they are what human beings do all the time, tell stories, but I'm conscious that you can overegg that at times."

And the Land Lay Still examines that nature of narrative and the human compulsion towards it brilliantly. About halfway through the book, readers might wonder where the author is taking them, but by the final section, the disparate stories coalesce into something subtle and profound, without the fictional artifice of having all the loose ends tied up.

Often in novels with many narrative threads, the interconnectedness of the characters seems a little contrived, but there is something about the overlapping in Robertson's work that rings true. "That interconnectedness does happen in all cultures and societies, but in Scotland it happens all the time because it's such a small place. So much so, I've given up being surprised by it," he laughs. "Someone in the book says, 'Here's a room with 250 people in it. If you wanted to draw a spider chart of how Scottish society works, this is all you need, because from here it goes out to everywhere.'"

Although not solely a political novel, the politics of Scotland run like a seam through And the Land Lay Still. North Sea oil, the Poll Tax, the Thatcher years, the miners' strike and the devolution referendum of 1979 are among the landmark events that affect all the characters, from miners to artists, secret- service agents to landed gentry.

What strikes home most forcefully after reading the novel is how extraordinary the change in attitude has been towards Scottish nationalism. Robertson was politically active throughout the 1980s and 1990s, campaigning for self-determination, but the novel is far from being a polemic on the subject; more a balanced reflection of how attitudes have changed.

"Politics was the initial motivation. I thought there was an interesting story to be told about the politics of a country like Scotland and how it's changed over the past 50 years. After the Second World War, Scotland was probably as British as it was ever going to be. Being a Scottish nationalist was almost seen as a sign of lunacy back then. There is a lot about the politics of nationalism in this book, but I don't particularly adhere to an ideology of nationalism. I think it's about becoming more normal as a country."

Throughout his career, Robertson has also been heavily involved in the politics of language. His first two novels contained large chunks of Scots mixed in with English, while And the Land Lay Still is written almost entirely in standard English, with occasional working-class Scots accents thrown in. At the same time, his work with Itchy Coo, partly funded by the Scottish government, has exposed a whole generation of schoolchildren to a written version of the language they grow up speaking, helping to legitimise it in the process.

"One of the things I feel very strongly about is that children, when they arrive in school, should not be told suddenly that the way they've spoken for the past five years is wrong," he says. "Every Scottish person has to be conscious that there's something going on linguistically in this country which does not conform to standard English, irrespective of how you feel about that. To have Scots in your toolbox as a human being – regardless of whether you're a writer or not – to be articulate in different languages, we should always encourage that."

Issues of nationalism and language aside, And the Land Lay Still remains a universal tale, in which the passage of time and the changing generations have led to a radically different world from the one that existed half a century ago.

"This is not the story of Scotland, this is a story of Scotland," says Robertson with a smile. "It happens to be Scotland because that's where I live and what I know, but it could be anywhere. The same changes have happened all over the world."

The extract

And the Land Lay Still, By James Robertson (Hamish Hamilton £18.99)

'...Whatever else we put faith in will, in the end, betray us or we will betray it. But the story never betrays. It twists and turns and sometimes it takes you to terrible places and sometimes it gets lost or appears to abandon you, but if you look hard enough it is still there. It goes on. The story is the only thing we can really, truly know'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks