The night Samuel Beckett was nearly stabbed to death by a pimp

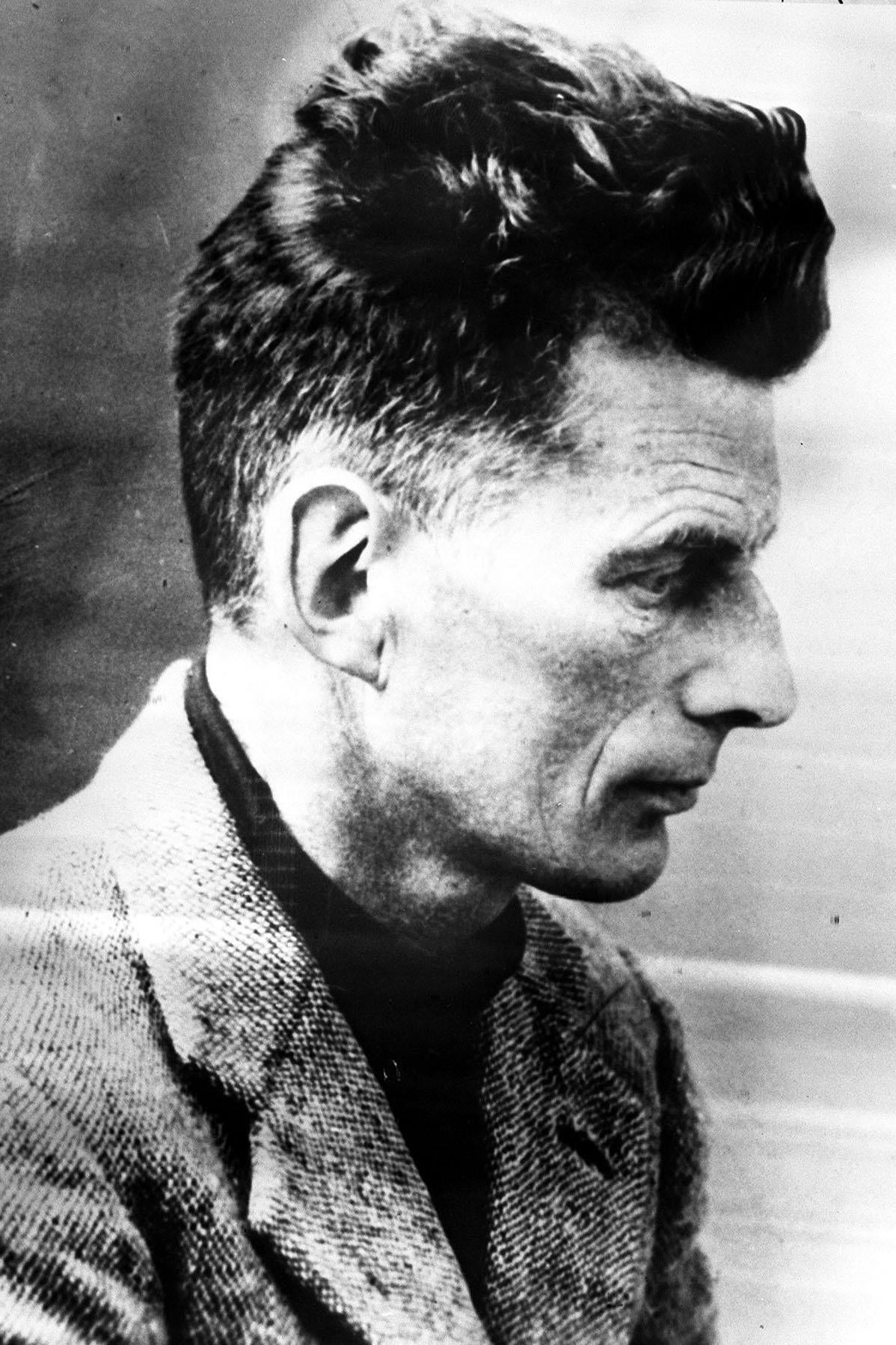

On the 30th anniversary of Samuel Beckett’s death, Martin Chilton revisits the chance encounter in which a pimp’s knife narrowly missed the writer’s heart, and ended up transforming his life forever

There’s no cure for being on Earth, Samuel Beckett used to joke. In 1938, one event in his own life had all the elements of absurdity, black comedy and fatalism that pepper his finest works, such as Waiting for Godot or Krapp’s Last Tape. It happened on a Paris street, when an argument ended with the writer being stabbed by a small-time pimp. He narrowly escaped dying of his wounds.

There was a whiff of farce, too, with the newspaper accounts of the attack, Le Figaro reporting that “Samuel Peckett” had been stabbed in Paris. Beckett survived the assault, went on to win the 1969 Nobel Prize for Literature, and kept going until his death, in the same area of the French capital on 22 December 1989, at the age of 83.

At the time of the stabbing, Dublin-born Beckett was 31. He had moved to Paris to build a literary career, which had gained traction with his first set of short stories, 1934’s More Pricks than Kicks. Other accounts of his attack were confused. Reuters sent out a wire story with the headline, “DUBLIN WRITER STABBED”, in which it reported: “Mr Beckett was seeing some friends home when he was pestered by a tramp.” The agency said he was knifed after “a scuffle”.

Beckett was actually attacked in the early hours of 7 January 1938, after being confronted in L’avenue de la Porte-d’Orléans by a pimp with the wonderfully improbable name Prudent. Beckett, who was working on the final drafts of his novel Murphy, had been to the cinema with his friends Alan and Belinda Duncan. They were walking home when the writer was stopped by Prudent, hustling for money. Deirdre Bair, in Samuel Beckett: A Biography, described what happened next. “Beckett, irritated, flung his arm away, pushing Prudent to the ground. The pimp jumped up, whipped out a clasp knife and shoved it into Beckett’s chest, narrowly missing his left lung and heart.”

Beckett fell to the ground, bleeding profusely. The knife had missed his heart only because the heavy overcoat he wore halted its penetration. Another biographer, Anthony Cronin, suggested in Samuel Beckett: The Last Modernist that the pimp was known to the young author, having “on occasion fixed Beckett up with a girl”. This connection does not tally with the account Beckett gave to biographer James Knowlson, nearly half a century later. In Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett, the writer is quoted as saying: “This pimp emerged and started to pester us to go with him. We didn’t know who he was until later, whether he was a pimp or not. This was established later, when I identified him (from photographs) in hospital. Anyway, he stabbed me; fortunately, he just missed the heart. I was lying bleeding on the pavement. Then I don’t remember much of what happened.”

Beckett was rushed to the nearby L’hôpital Broussais, where he came close to dying. His friends rallied round. He had known Irish writer James Joyce for a decade, although their friendship had cooled after his problematic romance with Joyce’s daughter Lucia. The author of Ulysses paid for Beckett to have a private room at the hospital and even took in his own reading lamp to make it easier for Beckett to concentrate on correcting the proofs of Murphy.

Beckett’s mother Maria had learnt of the attack from a relative who happened to see a newspaper billboard in Dublin with the headline: “Irish Poet Stabbed in Paris, Early Morning Attack”. The former nurse, who had been widowed since 1933, came to see him, along with Beckett’s elder brother Frank. “I felt great gusts of affection and esteem and compassion for her when she was over… what a relationship,” Beckett later told Knowlson.

Beckett loved living in Paris. He worked first as a lecturer at the Ecole Normale Supérieure and later stayed there to build a career as a writer. He had no desire to return to Ireland, a place he fled after a spell teaching at Trinity College, Dublin. When he handed in his notice after four terms, a fellow lecturer had been incredulous, saying: “But here you are teaching the cream of Irish society.” It prompted Beckett’s memorable retort: “The cream of Ireland… rich and thick.”

Despite his mother’s hopes that he would come home, Beckett was steadfast about staying in Paris. He was released from hospital on 23 January 1938 and later attended Prudent’s trial. Beckett met his assailant in court and asked him the reason for the attack. “Je ne sais pas, monsieur. Je m’excuse” (“I don’t know, sir. I’m sorry”) was the pimp’s deadpan reply.

The irrational, uncomprehending response could easily have come from one of Beckett’s own protagonists. More than the stabbing itself, the reply, highlighting the randomness of life, seemed to Beckett to encapsulate what an absurd joke on the part of fate his brush with death had been. Beckett wrote to his friend Thomas McGreevy to say that he found his attacker “more cretinous than malicious”.

Beckett may even have been amused by his assailant’s response. He chose not to press charges. Prudent spent time in prison, and even hearing about this experience tickled the writer. “There is no more popular prisoner in the Sante,” Beckett wrote to a friend. “His mail is enormous. His poules (prostitutes) shower gifts on him. Next time he stabs someone they will promote him to the Legion of Honour. My presence in Paris has not been altogether fruitless.”

Although Beckett jested about the violent incident, it left psychological and emotional scars, and certainly coloured his imagination. In Memory and Narrative: The Weave of Life-Writing, James Olney, a professor of English at Louisiana State University, argues that the stabbing was “an important turning point” for Beckett’s writing, in works such as Waiting for Godot and The Unnamable. “It was not the near-death that made the experience significant,” says Olney, “but the noncommittal response about the reason for the assault… ‘I don’t know’ or equivalent expressions are everywhere in Beckett from this point on.”

The time in hospital also marked a turning point in Beckett’s personal life. In the fortnight before the assault, Beckett had a torrid affair with the wealthy Peggy Guggenheim. While he was in hospital, he was visited by Suzanne Déchevaux-Dumesnil, a 38-year-old former nurse and musician he first met at the Ecole Normale Supérieure in the 1920s. They had become close friends, sharing games of tennis – and seemingly much more. She read about the stabbing and rushed to the hospital. “Beckett’s nature and outlook had their drawbacks,” noted Cronin. “It may be regarded nevertheless as a blessing that he tended to rejoice in calamity when it came.”

His friendship with Déchevaux-Dumesnil was rekindled. She offered to help him recuperate at home. “I made scenes, she made curtains,” was Guggenheim’s caustic evaluation of why Beckett chose a supposedly more domesticated rival over her. Whatever Beckett’s reasons, Déchevaux-Dumesnil became his partner for the next 50 years. It was with her that Beckett fled the Gestapo, travelling on foot at night and sleeping during the day. The pair married in Folkestone in 1961.

Beckett could certainly never be considered an optimist. There is an oft-told anecdote about the time he was walking through a London park with a friend on a glorious sunny day. “It’s the kind of day that makes one glad to be alive,” said his companion. “I wouldn’t go that far,” Beckett reportedly responded.

Surviving the stabbing made the writer reflect on his own obsession with his health. Four years before Prudent’s assault, he had undergone a course of psychotherapy at London’s Tavistock Clinic with Wilfred Ruprecht Bion. Aged 27 at the time, he had complained of “severe anxiety symptoms” and detailed night sweats, shudders, feelings of panic, and breathlessness. When he was at his worst, he said he suffered “total paralysis”. In letters from this period Beckett described a range of ailments, from “sebaceous cysts” and “lumps between the wind and the water” to “heart palpitations”.

Whether it was two years of analysis or being stabbed by a pimp is unclear, but Beckett does seem to have been less dogged by hypochondria in middle age. He remained fit and healthy until his bad habits caught up with him as an old man. The young student who had been good at tennis and cricket – he was also a demon at bar billiards – in old age walked slowly and suffered from emphysema, a condition exacerbated by years of puffing on cheap cigarettes in the cafes of Paris. Beckett also suffered from psoriasis and eczema and, like the characters in his plays, he had “disorders of the feet” and “trouble with the joints”.

Dr John Wallace wrote about Beckett’s failing health in 2010 article for the Irish Medical Times. Wallace recounted why the writer’s French doctor placed the 80-year-old in a state-run nursing home called Le Tiers Temps, in Paris’s run-down 14th arrondissement. “Beckett’s health was in serious decline by 1986,” summarised Wallace. “Beckett had experienced dyspnoea for some time and he began to use oxygen more frequently around this time. He had also suffered a number of falls and his friends had begun to suspect that he was not eating properly when he was at home.”

Although some visitors complained that the austere nursing-home accommodation was “unsuitable”, Beckett’s small, barely furnished ground-floor room, with a view on to a courtyard, had a simple, monastic atmosphere that appealed to the writer. The only thing he complained about was the wallpaper. He liked the routine of the home and joked that his fellow guests were “startlingly convivial old folks watching television”. He had no telephone and the residents would hobble round and obligingly summon Beckett to the phone at reception if there was a call for him.

Beckett enjoyed his regular Irish whiskeys – Bushmills, Jameson and Tullamore Dew were his favourites – and an occasional glass of Guinness. He watched cricket, football, the Irish rugby team and the French Open tennis on television. He remained an avid reader and had biographies of Oscar Wilde and Nora Joyce on his shelves, along with a copy of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Despite his difficulties in breathing, he continued to smoke Havanitos Planteros cigarillos, puffing away happily while listening to his beloved Schubert on a small stereo. When his poet friends John Montague and Derek Mahon visited, Beckett reminisced about his youthful walks in the Dublin Hills.

On 17 July 1989, Déchevaux-Dumesnil died, at the age of 88. A solemn Beckett attended the funeral and was never quite the same after he returned to the nursing home. On 6 December, Beckett was discovered unconscious by a nurse and taken to hospital. A fortnight later, he sunk into a coma and died on the morning of 22 December, of respiratory failure.

The writer who once said “I could not have gone through the awful wretched mess of life without having left a stain upon the silence” was buried in secret on Boxing Day 1989. He was later interred with his wife in Paris’s Montparnasse Cemetery. There was no clergyman, no religious service and no speeches at Beckett’s funeral.

That silence would have amused Beckett. Shortly before he died, while living in the nursing home, Beckett composed his final poem, What is the Word. It was written for Joe Chaikin, a friend who had suffered a stroke. Beckett’s last creation reflects on the folly of the fruitless compulsion to search for the right words.

Aged and ill, Beckett still had a mastery of language. Thank goodness that thick overcoat saved him from Prudent’s blade on that fateful night in 1938. The world was blessed with the masterpieces he went on to carve out.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks