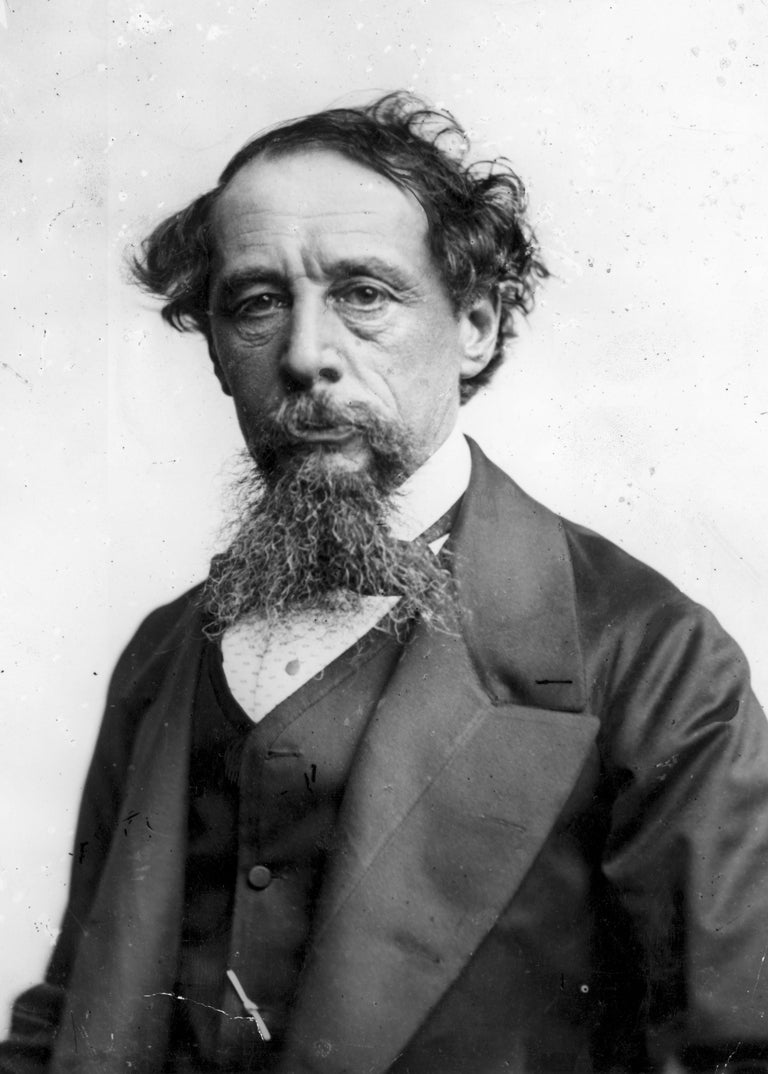

Saint and sinner: Biographer Claire Tomalin has taken Charles Dickens for her last big subject

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Claire Tomalin remembers her first reading of a Dickens novel: David Copperfield, when she was around seven years old. "That book was an overwhelming experience." Like so many people of her generation, she also recalls the bindings of the collected Dickens edition on family shelves. Some friends have cast doubt on the likelihood of this precocious taste, but "I was a terrific reader and my mother loved Dickens." As did her French grandmother (she was born Claire Delavenay), who – as the dedication to her new biography tell us - read the same novel, in English, at boarding school in Grenoble, in or around 1888. Tomalin even inherited family stories of a great-great grandmother who told of the excitement as each new instalment of Mr Dickens's latest bestseller left the press to enrapture a vast adoring public, in Britain and beyond.

To buy this book from The Independent's bookshop, click here.

Dickens's work has meant so much, to so many, for so long. From the late 1830s, the monthly parts of Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist first built a mass readership for the firebrand parliamentary reporter with a feckless Navy pay clerk for a father (the model for Mr Micawber), a fractious, hard-up family and a childhood shadowed by debt, disruption and that notorious spell in the shoe-blacking factory at Charing Cross. Now, almost 180 years later, Dickens returns in glory via the latest TV and film versions of Bleak House, Little Dorrit or Great Expectations - with two of those planned.

So the meteor that streaked across the sooty skies of pre-Victorian London has not yet come to earth. Tomalin appreciates the dramatisations, and she notes that, from the beginning, theatre managers cashed in on the multi-media appeal of Oliver, Fagin, Pickwick, Smike and their imperishable successors: "They were played all over England in terrible adaptations that made Dickens groan."

Yet she worries that the swarming theme park of DickensWorld has obscured the colossal verbal energy and artistry of a literary magician with few equals in any age: "People tell me that at universities nowadays, EngLit students write their answers on the basis of having seen the television... Don't people realise that words on the page are what matter?" Meanwhile, she has met resistance from the grandson to whom she sent some Dickens: "Children really do have shorter attention spans, and they find it difficult to get into 19th-century books."

With dozens of celebrations, festivals and publications scheduled for the Dickens bicentenary in 2012, his comet still blazes. At the same time, not only the words but the charismatic, tireless and exasperating man who wrote them run the risk of occlusion by the myth. Tomalin's biography Charles Dickens: a life (Viking, £30) of course enters a crowded field. But she brings to it all the peerless ability to match scholarship to storytelling that won acclaim, and honours, for her lives of Mary Wollstonecraft, Samuel Pepys, Thomas Hardy, Jane Austen, Katherine Mansfield – and of actress Ellen Ternan, The Invisible Woman, Dickens's later-life mistress. As a biographer, Tomalin remains (as her subject called himself ) "inimitable".

Now 78, she sits on a sofa in the quirkily pretty house close to the Thames near Richmond where she lives with her husband, Michael Frayn. Outside, a large and lush garden thrives under the September sun. Over the wall, traffic rumbles down a busy road. Dickensians might think of Wemmick in Great Expectations, pulling up the drawbridge to guard domestic bliss.

A first-class Cambridge graduate, Claire Delavenay married Nicholas Tomalin, the flamboyantly gifted journalist killed in Israel during the Yom Kippur war of 1973. She rapidly had five children; one died in infancy; one had spina bifida. Dickens's perilous family life does not stand so far apart from ours. In the 1970s, she became an esteemed literary editor of the New Statesman and Sunday Times. Her run of beautifully crafted biographies began in 1974 with The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft. In 1980 she met already-married Frayn; they soon became a couple, but only married in 1993.

Now she talks of Dickens and his world with the sort of shrewdness, candour and animation that the mighty foe of humbug would surely applaud - even when it hurts. Thanks to the panache of its narrative and the bite of its insight, her biography strips the cobwebs and the kitsch from the spellbinder who "saw the world more vividly than other people, and reacted to what he saw with laughter, horror, indignation – and sometimes sobs".

Tomalin paints Dickens as a divided soul who juggled double lives. As a benefactor of the poor and weak, his "goodness and generosity" often astonishes. We meet him in 1840, taking a break from his punishing routine to save a friendless servant-girl with a dead infant from the gallows. As Tomalin says, "He was an intensely good man. And he turns into a frightful villain." Not surprisingly, she makes much of a little-known account by Dostoyevsky of the two titans' sole meeting, in 1862. "There were two people in him, he told me," reported the Russian: "One who feels as he ought to feel and one who feels the opposite," Tomalin gives both Scrooges their due.

In The Invisible Woman, published in 1990, Tomalin pieced together hints and reminiscences from friends and family to deliver a full-length portrait of Nelly Ternan, who not only became Dickens's lover but, she believes, bore him a son who died in infancy. It turned her into a "bad person" for the more reverential Dickensians, she says.

But she did no more than trust the evidence supplied by Henry and Katey, the two brightest of the ten often gormless, drifting children born to Catherine Hogarth, the wife whom Dickens came so cruelly to reject. "I accept it" – the existence of the child – "because Henry and Katey said there was. They were two very intelligent people, and they loved their father," Tomalin insists. The new biography proposes that the Staplehurst train crash of 1865, after which Dickens (a passenger) heroically aided the survivors, came about just as he and Nelly were returning from France after the death of their little son. For Tomalin, "It was absolutely a turning-point for Nelly herself: to realise that in this sort of situation, he would go out to help other people, and you would have to be bundled off."

His public repudiation of Catherine still has the power to shock. As the book puts it, "you want to avert your eyes" from Dickens's behaviour. For Tomalin, "It's a very banal situation: your middle-aged wife is getting fat and you're irritated by her." She still found this descent into bullying selfishness by a man capable of such nobility "really distressing. You have to say that a lot of people go through a period in their life when they behave like mad people." She mentions Chris Huhne. "I've behaved badly in my life. I hope I haven't behaved as badly as Dickens! In a way, if you're a woman, you're not in a position to behave as badly, because you don't have the economic power. So you're more likely to be the Nelly figure than the Dickens figure."

Hilariously (in retrospect), the fervent champion of hearth and home wanted around the time of the split to launch a new magazine called "Household Harmony". As Tomalin reports, "'It takes dear Forster" – John Forster, Dickens's best friend and authorised biographer, who emerges from her book as an upright, selfless champion but no flatterer – "to point out that people might be a bit surprised, having read his statements about his marriage."

About the hapless Catherine, wed young to this unquenchable ball of literary fire and reforming zeal, Tomalin judges that "She was crushed. Dickens arranged everything, organised everything – where they lived, how they lived, who they entertained. She was nominally in charge domestically, But there was no space for her. That was the real trouble." Baby followed baby. Sending them to wet-nurses, rather than breast-feeding, meant that Catherine would rapidly resume menstruation. Dickens "never attempted to find out about birth control of any kind," Tomalin reports, "although he desperately didn't want to have more than three children. It's as though he was embarrassed. I think he wanted to get married because he didn't want prostitutes but he wanted sexual hygiene – and marriage was sexual hygiene."

Thanks to Tomalin's artful deployment of many sources, some hitherto obscure, she lets us see Dickens through female eyes at pivotal points. They admire the warmth, the zest, the flaming genius, but seem to intuit something a little monstrous. None cuts deeper than daughter Katey, who told Bernard Shaw in 1897 that she sometimes wished to correct the view of her father as "a joyous, jocose gentleman walking about the world with a plum pudding and a bowl of punch." From his super-wealthy friend Miss Coutts to the former prostitutes for whom this odd couple of phianthropists opened a – non-punitive, non-sanctimonoius – home at Shepherds Bush, Dickens knew women of all sorts and conditions, many in his own family. So why the drippy heroines, from Little Em'ly in David Copperfield to Bleak House's Esther or Little Dorrit herself? "I sometimes think to myself that Dickens couldn't really do women in life and he couldn't really do women – I mean nubile women – in books," Tomalin says.

Amy Dorrit she defends as a "poetic" creation: an "emblematic figure who moves through this awful, corrupted, smelly, filthy London – untouched". In general, she says, Dickens "might say that it wasn't possible to write about life as it really was and bring a blush to the cheek of a young person. He felt he was cut off from doing that – and perhaps all the more cut off as he was running a home for prostitutes."

For all the protean complexity of the man we meet in Tomalin's gripping, galloping pages, the stature of the writer seems less shadowed by doubt. For her, "No one except Shakespeare and Chaucer has created characters that have passed into the language. And they passed so quickly into the language – and have stayed!"

Her re-reading of the entire works not only sealed her admiration of the masterpieces, from Copperfield through to the majestic Great Expectations: "delicate and frightening, funny, sorrowful, mysterious". It also re-awakened affection for the youthful fizz first on show in 1836 in Sketches by Boz, which "really enthralled me. Partly because it's wonderfully written, but also because it tells you what Dickens was looking at in those years when we don't know much about him."

Even dedicated Dickensians will know, and understand, much more about the novelist after reading Tomalin's close-packed but free-flowing narrative. Yet it represents her swansong as a large-scale biographer, she says: "I cannot give four or five years of intense labour to another book. I love my grandchildren, and there's Michael – and his children and grandchildren. And I want to play the piano; I want to garden." As for now, "I would perhaps like to go back to writing small books about obscure people."

We shall see. For the moment, she has captured Dickens, in sun and shadow, with all the full-hearted exuberance, generosity and keen wit that he merits. A lifelong Francophile, he once complained that the prudish English climate denied novelists the freedom to explore all sides of life, as their French counterparts could. So might this supreme master of archetypal melodrama ever have written as a psychological realist à la française? "If he was talking about sexual frankness, then he could have had more of that in his books," Tomalin says. "But the difference, certainly from Flaubert, was huge. The whole approach to life was entirely different. Flaubert is rather a despiser of human beings. Dickens is a lover of human beings; a relisher of human beings." As is his biographer.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments