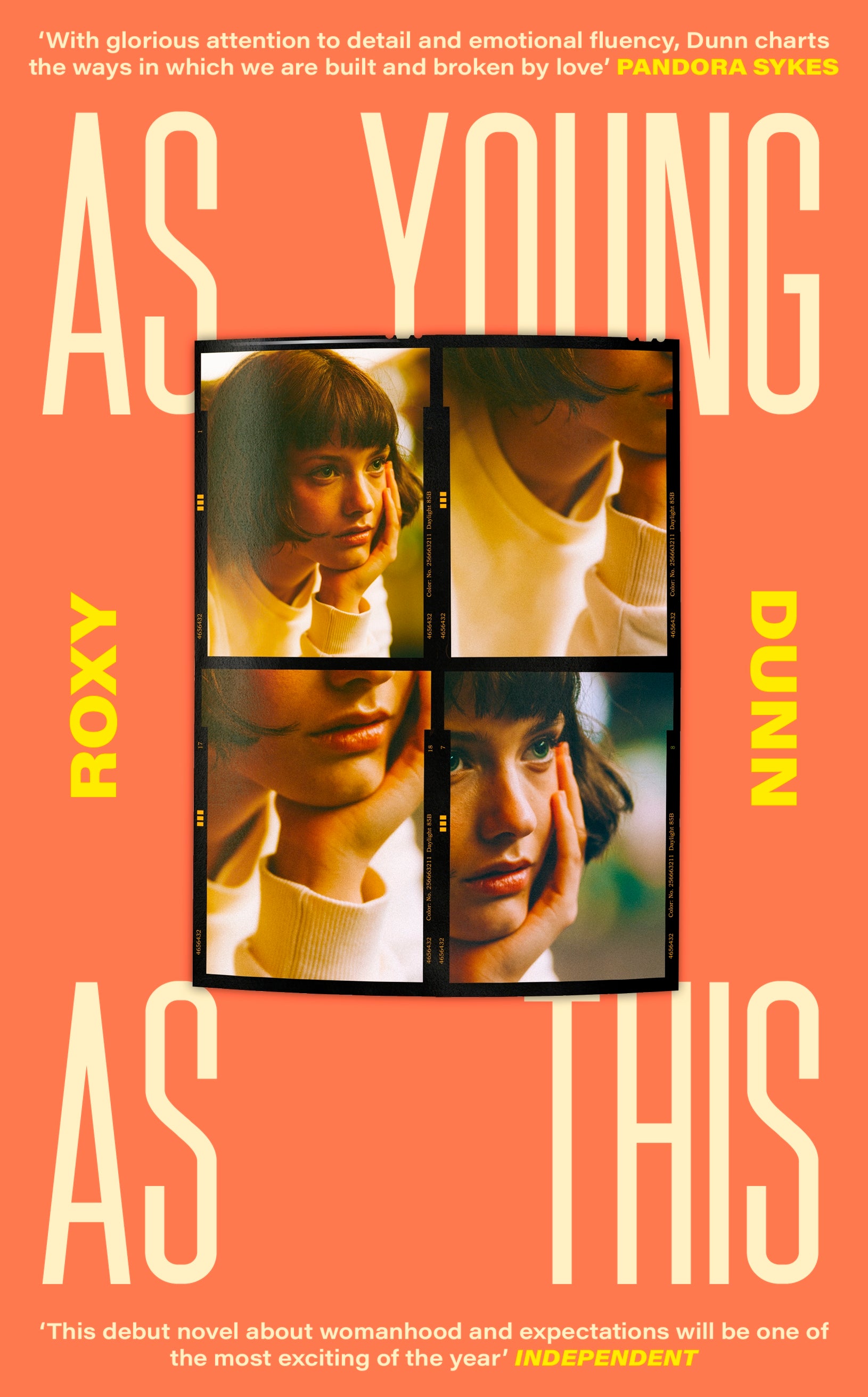

Roxy Dunn’s As Young As This and the novels exploring the thirtysomething fertility question

Many of us are ticking off the traditional markers of adulthood much later than anticipated but, as thirtysomething women are constantly told, the biological clock keeps ticking at the same rate. Roxy Dunn’s debut novel is one of a wave of novels exploring very modern fertility conundrums, writes Katie Rosseinsky

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Women are born with a lifetime’s supply of eggs: a finite number, estimated to be between 1 and 2 million, which declines every month. It’s a fact that springs into the mind of Margot, the protagonist of Roxy Dunn’s debut novel As Young as This, around her 34th birthday. She’s struck by how unfair it is. “What a waste, all those eggs being available when you didn’t want them,” she thinks, “preparing your body to do something you hadn’t been in any way – aside from biologically – ready to do. How many are left inside you now?” Why, she wonders, hasn’t the female body somehow evolved to better accommodate a more modern timeline, one where many of us use our twenties as a test run for adulthood, settling down later than our parents did?

Returning to this passage makes my stomach do a flip (and not the good kind). I’m a few years younger than Dunn’s character, but her interior monologue may feel familiar for thirtysomething women who always vaguely assumed they’d have had kids by now, but, at the same time, barely feel adult enough to take care of themselves. “How many are left inside you now?” – it’s the sort of question that floats into your head, entirely unwanted, when you’re struggling to drift off to sleep. Or, when you’re queuing up to buy a “congratulations” card with a picture of a stork on it for a friend. Or when an algorithm drags a sponsored advert for an at-home fertility test, featuring a 25-year-old influencer, into your social media feeds. These thoughts, though, tend to stay as just that – thoughts. They remain unspoken, because they’re a bit vulnerable, a bit personal, a bit embarrassing. Perhaps that’s why seeing them on a page feels so confronting.

The existential crises of twentysomethings – who am I, and what do I want to do with my life? – have always provided rich territory for novelists, especially younger debut authors, writing what they know (even if it’s normally not much at that stage). But now that period of uncertainty can stretch out well into our thirties, in no small part thanks to extortionate housing costs placing the traditional markers of adulthood out of reach. When Bridget Jones was the only single person in her friendship circle back in the Nineties, at least she could wallow in the comfort of her Borough Market one-bed without having to dodge someone from SpareRoom – even if you are in a stable relationship, it’s hard to seriously consider having children if you’re living in a house share. And, as Dunn suggests, this new timeline doesn’t necessarily match up with the female biological clock.

When As Young as This opens, Margot, who is an actor-turned-writer like Dunn, is on the verge of making a major decision about her fertility. But before she goes ahead with it, she looks back at the romantic relationships that have acted “like stepping stones”, bringing her to this point. There’s a chapter for each of them: the short-lived teenage boyfriend, the ill-advised infatuation with an older, married actor, the on-off romance with a commitment-phobic comedian, and the one who seems like “the one”. She has always taken an empirical approach to dating, we learn as the novel progresses, assessing each partner’s traits against the men who preceded them (“Surely it actually makes sense to arrive at the decision through a series of adjustments based on previous results?” she tells the flatmate who questions whether she’s overthinking it).

While this retrospective of her past relationships is funny, relatable and full of 2010s “period” detail, Margot’s thoughts on motherhood are the novel’s through line. As Young as This joins a wave of novels exploring thirtysomething women’s often jumbled feelings about their fertility and having kids, articulating experiences that aren’t often dealt with in fiction, whether that’s because they’ve been considered taboo – like choosing to be child-free – or because they’re dealing with relatively new fertility treatments. In Chloë Ashby’s novel Second Self, released last summer, the protagonist reconsiders her previous ambivalence towards motherhood, eventually opting to freeze her eggs. Olive by Emma Gannon explores how the protagonist’s decision not to have children untethers some of her closest relationships, while one plot strand of Nikki May’s Wahala – a portrayal of a thirtysomething female friendship group – covers similar territory. And Expectation by Anna Hope zeroes in on the slog of IVF treatment (and what happens when your best friend seemingly manages to conceive effortlessly).

For As Young as This’s Margot, unlike some characters in those stories, it’s not about the question of “kids or no kids”. She has always known that she wants to become a mother one day. As a young girl, we learn, she “privately fantasised about motherhood, attempting to conceal the level of [her] longing, for fear of sounding strange and matronly”. As a teenager, she “keep[s] a list of potential baby names on a scrap of paper inside an old tin”, crossing out contenders and adding in new ones. By the time she reaches her early thirties, the desire to have children manifests as an “active ache”. It’s rare to see the plight of a single woman who wants kids treated seriously and with empathy, without being seen as either somehow secondary to that of a couple, or being written off as somehow a bit cringe or even anti-feminist.

It’s rare to see the plight of a single woman who wants kids treated seriously and with empathy

The men that Margot dates are sometimes upfront about their attitude to kids. One of her earlier boyfriends, Oliver, is “openly unsure about wanting them”, but his “ambiguity” and the fact that she is “in no immediate rush” keeps her clinging to the relationship. Others state one intention then later retract it, leaving her to realise that she has built a life plan on shaky foundations. They are not, Dunn’s story emphasises, subject to the same time pressures and social imperatives as Margot, and this only makes her forays into dating all the more frustrating. It’s no wonder that, after one major breakup, “the thought of starting again exhausts [her]”. “Is there even time for that?”, she wonders. Of course, hers is just one (straight, female) perspective on a complex subject. It’d certainly be interesting to read the male counterpoint. Perhaps, though, the very fact that there aren’t many books providing this proves Dunn’s point. The question of if and when to have children simply lacks the same urgency for men.

Maybe it would be easy for Dunn and her fellow authors to frame fertility treatments like the one Margot considers as a simple solution, even as an alternative to the more traditional “happily ever after” (the character explores intrauterine insemination, or IUI, as a way to have a child using donor sperm, a less expensive form of IVF that also has lower success rates). But when I’ve spoken to women who’ve frozen their eggs, for example, many of them mentioned that although their decision was a positive step, it was one tinged by a sadness – that things hadn’t worked out for them in the way they had expected when they were younger. “This wasn’t meant to be part of [my] story,” Margot thinks at one point. She is sick of being called “brave” by well-meaning friends, and admits that she sometimes resents her situation. Making a decision about fertility, whether that’s egg freezing or going down the solo parenthood route, can be incredibly empowering – but empowerment is just one of a whole spectrum of feelings it will likely provoke. It would be a disservice not just to characters like Margot but to their readers as well to pretend otherwise.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments