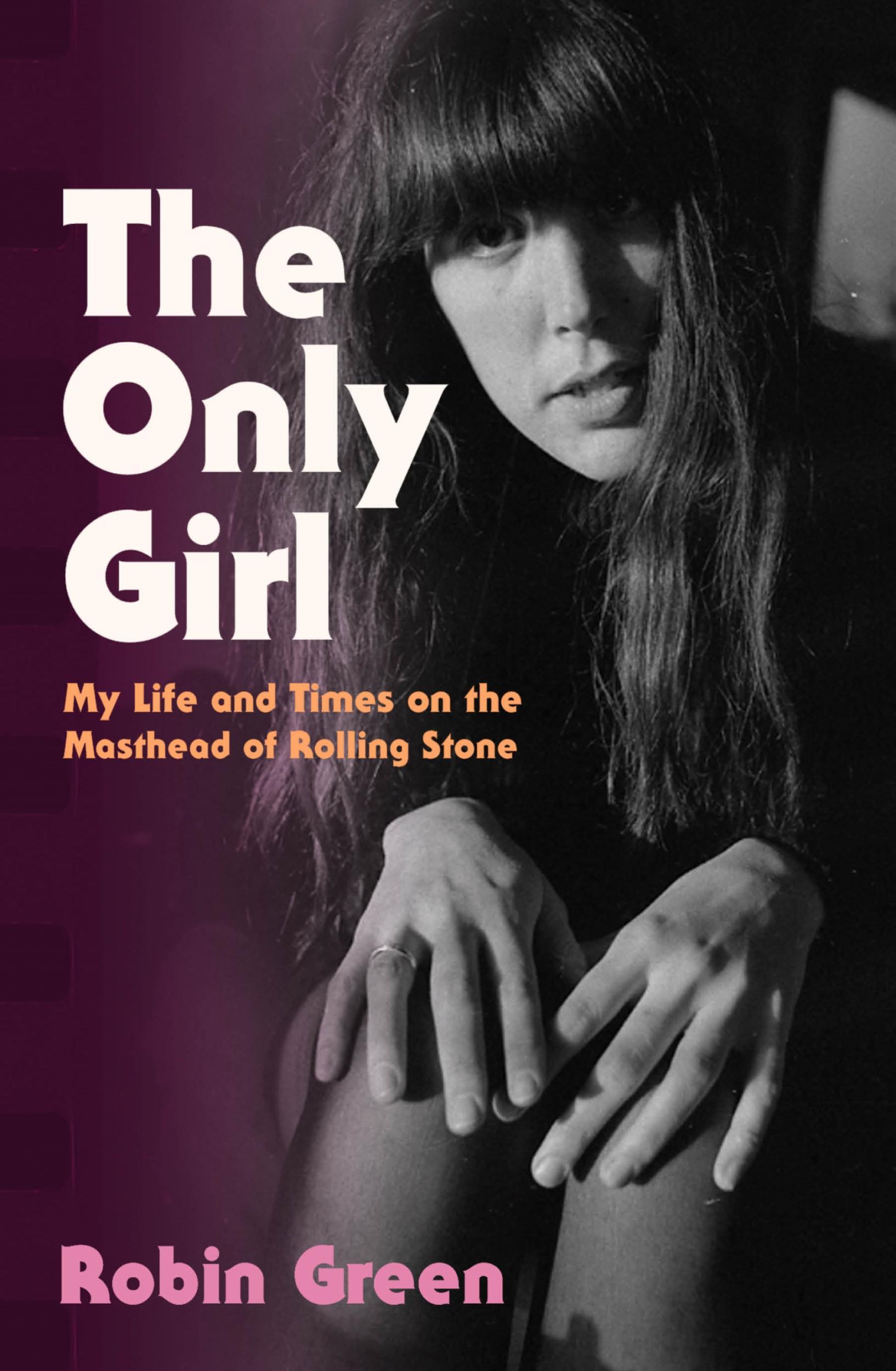

Robin Green on being the only female journalist on the masthead of 'Rolling Stone' in the 1970s

Green's confessional memoir is a fascinatingly direct account of a woman in a man’s world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Of the many illuminating chapters in Robin Green’s new memoir, The Only Girl, in which she recounts her time as the sole woman writing for US music magazine Rolling Stone during its early 1970s heyday, the one entitled A Big Journalistic No-No is surely one of the more memorable.

Green, the well-educated daughter of “upwardly striving East Side Jews”, had never had any formal training to become a journalist, nor a particular desire to become one. When she drifted towards San Francisco in the late 1960s in the hope of dropping in on the offices of her favourite magazine, the very apex of her ambition was the possibility of landing a secretarial role. Instead, charmed by her deadpan humour, editor Jann Wenner was soon asking her to write 5,000-word cover stories on subjects ranging from David Cassidy to Marvel Comics, Green thereby almost instantaneously graduating to a level most rock hacks can only dream of.

“I was lucky, I guess,” she says, somewhat disingenuously.

Three years later she was thriving. It was 1973, a year in which, she writes: “I’d travel the country, and the world. Sleep with who knows how many men.” Then she received perhaps her juiciest commission: to write an in-depth article on the children of Robert F Kennedy. The research bore fruit: drugs, endless privilege, paranoia. But it was when she went back to the bedroom of one of them, Bobby Jr, and, in her words, “took [their] clothes off and had sexual intercourse on the waterbed”, that Green realised she might have crossed a line, and whatever she would write would be compromised as a result.

So she didn’t write it. Her boss wasn’t happy. He fired her.

“Jann had a habit of firing people and then hiring them back again. But you know what? I didn’t fight it. I was ready to go. It felt time to move on,” says Green.

It is a peculiar thing to say for someone in her position, then one of the most celebrated young writers in America, the cultural world at her feet. She was just 28 years old. What on earth would she do next? She waited tables.

“Hey,” she counters, “I liked waiting tables.”

Footnote: though she may have elected not to write about her liaison with a Kennedy in the magazine, she chooses to do so now, 45 years on, in her memoir. The Only Girl is a gripping read for all sorts of reasons, one of which is its candidness. Green likes to tell it as it is.

“What I found out on that undulating waterbed could have been key to understanding the Kennedy male,” she writes. “It wasn’t just his command of the situation, but what he looked like naked when he knelt before me. How to say it delicately? The guy was hung. Probably halfway to his knees.”

The confessional memoir is a complicated beast, requiring as it does full disclosure in pursuit of a compelling read. But many writers choose to err on the side of caution when it comes to chronicling others into whose orbit they stray – for reasons of diplomacy, etiquette, discretion. Not Green. She writes it all down. At one point she recalls going to bed with her editor and how disappointing she found him. “Well,” she tells me now, laughing, “I mean, he was gay…” – Wenner came out sometime later.

But this doesn’t make her book a cheap tabloid read; quite the opposite in fact. It’s a fascinatingly direct account of a woman in a man’s world – and no, she says perhaps surprisingly, she never had a #MeToo moment, was never taken advantage of by predatory rock stars – and also of just how far natural talent can take even the least ambitious of people.

“I never considered writing for a living,” she tells me earnestly. “That never even crossed my mind. I just sort of went with it.”

After crashing out of Rolling Stone – and that stint waiting tables – Green eventually returned to the West Coast, specifically Los Angeles, where a former colleague thought she might prove adept at writing for TV. Much as with journalism, she says, “writing for television had never occurred to me. But I tried it and I found that I loved it. I loved the drama of it, of not writing with my head but my heart. It was wonderful.”

She wrote for the hit show Northern Exposure before being hired by legendary TV writer David Chase, who at the time was developing the story of a troubled Mafia boss living in New Jersey. The Sopranos was subsequently hailed a landmark in television.

“People are saying it changed the whole medium of TV,” Green says, with what sounds like a shrug of the shoulders. “That’s nice.”

Her TV years proved as rich in incident as her Rolling Stone ones and Green, ever the straight talker, describes precisely what it’s like to work on a behemoth production for a boss who, according to her portrait of Chase, sounds a complete nightmare. He is described as variously petty, jealous and childish. Green routinely stood up to him and so inevitably became viewed, in the writers’ room, as a “negative presence”. Her firing was only a matter of time.

I tell her I’m surprised at just how much she chose to reveal about working for the man. Surely he’ll be furious?

She laughs uneasily. “Which version of the book have you read? Because I’ve taken a few things out. The British legal notes were much more stringent than the American ones, I guess because you have tighter laws around privacy.”

Nevertheless, she says, “everybody knows that David [is difficult to deal with]. Anything I say or do angers him! Even if I go to a party that he isn’t invited to, it pisses him off. I did tell the legal people that he would be the one to complain, but there is nothing in there, I don’t think, that he has any legal grounds for. He’ll be unhappy about it sure, and I’m sorry about that. But the purpose was not to piss him off; I just wanted to write an honest book.”

And that, clearly, is what she has done.

At 73, Robin Green believes she is done with TV, “at least for now.” She is considering writing a novel next, though confesses she has no idea how she might go about it. Still, it’s worth thinking about.

“You know that expression: over the hill? Well, I’m on top of it, I guess, and I’m looking down. I know that this thing is going to end soon, but I hope it doesn’t end just yet. I’m having fun, you know? I want to continue having fun.”

The Only Girl: My Life and Times on the Masthead of Rolling Stone, by Robin Green, is published by Virago

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments