Roald Dahl's Matilda at 30: A heroine who changed lives

The telekinetic bookworm taught young girls that it was OK to feel angry, says Daisy Buchanan

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s said that every good book is a self-help book, if you read it properly. It doesn’t matter how far a story lies outside your own experience if it contains characters you connect with, and words you can draw support from. Roald Dahl’s novel Matilda turns 30 today, and millions of readers have found comfort in its pages – and perhaps found themselves too.

I was eight when I met Matilda, slightly older than the eponymous heroine but not so old that I couldn’t see myself in her. Like Matilda, I was surrounded by bullies. I felt lucky that at least mine were playground-based, unlike Matilda’s family the Wormwoods, the acme of vulgarity (and if you love to hate the Dursleys, the Wormwoods will make you giddy with rage). Like Matilda, I was surrounded by people who thought intelligence was an inconvenience and a liability. Unlike Matilda, my method for dealing with my bullies was based on crying and hiding. I didn’t know there was another way, until this book came into my life and saved it. It was the Key Stage 2 Art Of War.

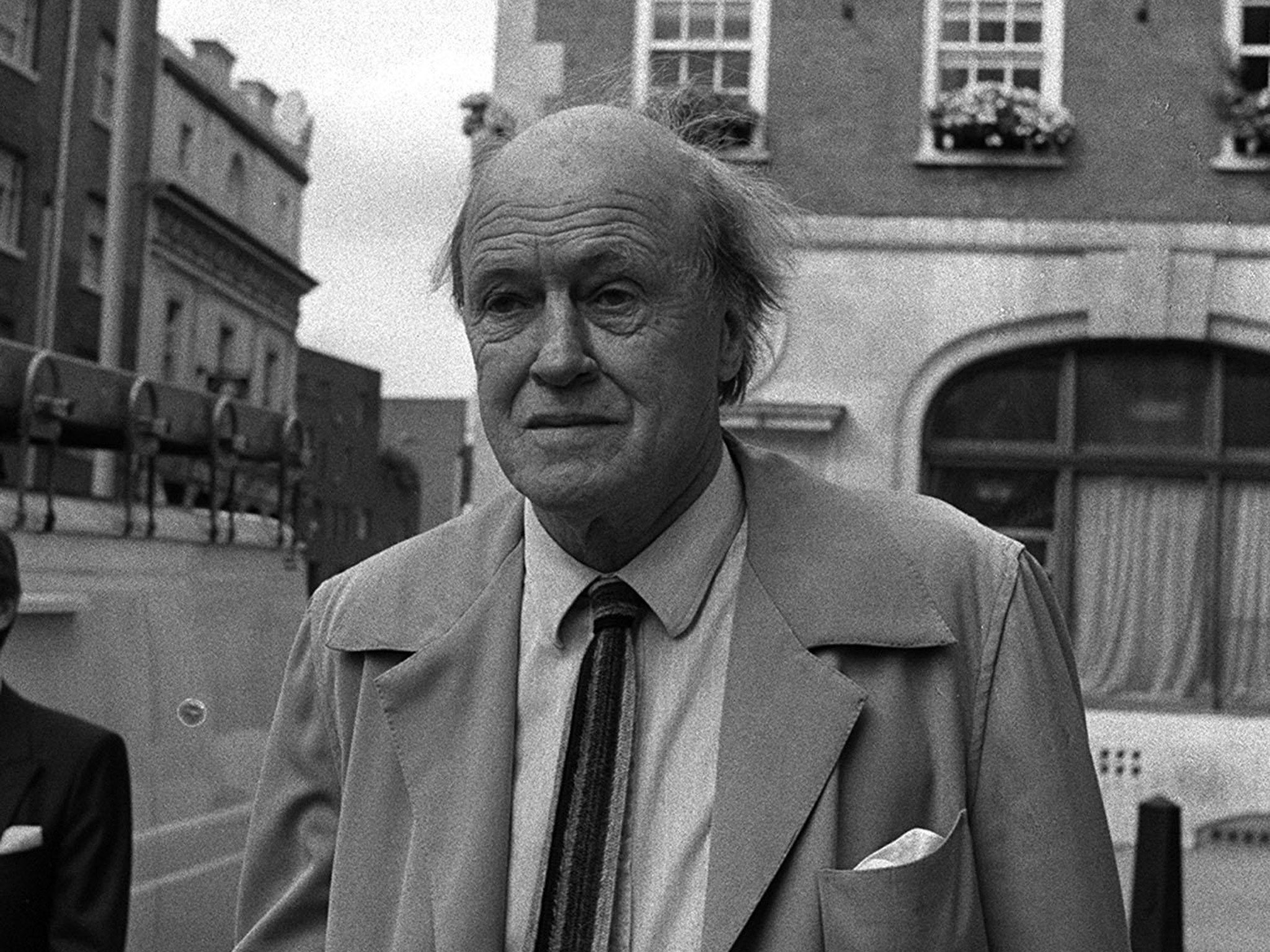

We can’t ignore the idea that Matilda’s creator, Dahl, was a problematic man. There are recorded instances of his antisemitism and compelling evidence that he was a misogynist and a bully himself. While I don’t want to defend Dahl, I do believe he wrote a heroine who changed the lives of his readers and inspired them to change the world for the better. (Many fans came to the story through Tim Minchin’s musical adaptation of the book, a global smash hit.)

The first time I read the book, the most vivid and shocking passage was a chapter called “Throwing the Hammer”, in which Miss Trunchbull, the bullying headmistress, picks up Amanda Thripp by her beribboned pigtails and throws her over the playground fence. Matilda watches the throwing and analyses it coolly. “[The] story sounds too ridiculous to be believed. And that is Miss Trunchbull’s great secret ... make sure that everything you do is so completely crazy it’s unbelievable.”

It was a chilling lesson, but it stayed with me. We can’t always trust people in authority to keep us safe. Bullies want power, and they take that power by making their victims feel frightened. Good will only triumph over evil when people think carefully and stay calm. (Three decades later, I worry that there are people in power who interpreted the book differently and are committed to making sure that everything they do is so completely crazy that it’s unbelievable.)

Matilda’s intelligence separates her – not just from the bullies, but from every other character in the story. However, she isn’t interested in using her cleverness as a label, or as a way of boosting her status. The moment she realises that her bullies won’t respond to reason, she decides to use her intelligence to survive their attacks.

But I don’t think Matilda is simply a book with a clever heroine. Reading it as an adult, I am sure that it’s a book about anger, and how effective rage can be when it’s channelled thoughtfully and intelligently. Female rage has always been a taboo. Like many women, I grew up being told that anger was an inappropriate emotion for little girls, and I was forbidden from expressing it. Yet Matilda’s rage gives her extra strength, and it becomes an extra source of fuel that powers her brain and allows her to seek revenge and justice.

Millennial women have grown up with Matilda – and if we assume the character was “born” at the same time as the book, we can just about claim her as one of our own. For women of all ages, throughout the world, life can feel dark, difficult and frustrating. Every day, there’s a new story about how we’ve been bullied by someone in power, and how our vulnerabilities have been exploited. We know that poverty affects women disproportionately, and that period poverty is limiting the education of girls through the UK (and indeed the rest of the world).

But millennial women are fuelling a new wave of activism and protest, becoming significantly more politically engaged in the wake of #MeToo, and leading effective campaigns against period poverty and FGM. Women in their twenties and thirties are bringing about significant social change by using the resources available to them – anger, intelligence, and humour. I’d like to think that over the past 30 years the spirit of Matilda slipped into our subconscious and we grew up with a blueprint for utilising our talents and our rage. We’re getting mad – and then we’re getting even. We might not be able to move objects with our minds, but like Matilda we can do magnificent things with our rage, if we use it thoughtfully and carefully.

The story of Matilda is empowering in the truest sense of the word. Admittedly, it hasn’t made its readers telekinetic, although I don’t know anyone who encountered the book during their childhood who didn’t attempt to move objects with their mind. Instead, the story has made hundreds and thousands of us feel seen and included.

It’s about a girl who turns a perceived vulnerability into a strength, who refuses to be alienated by her outsider status, and instead uses it to observe and learn. It is a book that brought me immeasurable comfort and strength when I felt that the word was failing me, and that I could only survive by hiding and keeping quiet. It’s the first book I thought of when I read Nora Ephron’s Wellesley college address, exhorting listeners to “be the heroine of your life, not the victim”.

The most important part of Matilda’s legacy is this message: children need to see themselves in the stories they read. I’ve talked to people whose lifelong love of reading was sparked by Malorie Blackman’s dystopian Noughts & Crosses series – which had people of colour as central characters – because, for the first time, they felt fully included in the narrative. In Lucy Mangan’s childhood reading memoir Bookworm, she describes the significance of discovering Gwen Grant’s book Private – Keep Out! and reading about a family dynamic that she recognised from her own life, but hadn’t found in any other stories. “At last,” she explains, “I could see my family from the outside in ... we were still in some fundamental ways outsiders. I think about Private – Keep Out! whenever arguments about diversity and representation in books break out. Imagine how much more would I have longed for and needed to see myself in my books if I’d been disabled, gay, black, non-Christian or something else outside the mainstream message?”

Last year, Simon James Green’s young adult fiction debut Noah Can’t Even had a gay relationship at its heart, but simultaneously told stories about bullying, fractured families, aspiration and envy (while including at least three great jokes on every page). Green’s writing proves that diversity is vital to telling great stories, but it doesn’t necessarily need to become the story itself.

Children are imaginative enough to see themselves in wizards, ghosts and people who lived thousands of years ago, but they need to recognise enough of themselves in a story in order to feel connected to it. Diversity and inclusion are unignorably important aspects of storytelling.

I understand why many readers feel that Dahl’s problematic place in history might exclude them from the stories he tells, but I hope that this anniversary inspires many more Matildas – stories written for all readers by writers who understand that books have a power that goes beyond magic. The power to make the marginalised and ignored feel dazzlingly visible – the heroines, not the victims.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments