Remembrances of a great poet: PJ Kavanagh

P. J. Kavanagh was the natural heir to Louis MacNeice. He praised MacNeice’s “wristy” manner and that is the key to his own best poetry. Commentators tend to refer to his nature poetry in the line of Edward Thomas and Ivor Gurney, his Catholicism, but like no other poet he captured that MacNeiceian rhythmic kick that drives the poem on.

Comparison with Edward Thomas, who, admittedly, Kanavagh loved, isn’t enough. In cricket terms, MacNeice and Kavanagh are Shane Warnes whereas Thomas bowls straight balls. Like MacNeice, Kavanagh wrote eclogues, the long occasional poem (‘Satire 1’) and, most of all, those wristy short lyrics.

Kavanagh was a poet of a kind that became extremely unfashionable from the Thatcher era onwards. Indeed, by now the type is extinct. He was a man of many parts, soldier (wounded in action in Korea), actor, journalist, editor, TV presenter.

His friend Peter Levi said that he had written “at least six to twelve poems on the shortlist for immortality”. That is true but the real test of a poet is: do some of their lines come to you unbidden while you’re just walking along, in different situations is your life? Not when you sit down to consume art of some kind, which is the current mode.

Some lauded poets never pass the unbidden-lines test: it cannot be faked. Kavanagh does: “while the auditioning stars on their cold blue xylophone go / ting! ting! ting!”; “for all I know men playing billiards temperately in there”; “and let me hear you laugh at my dustman’s’ hat”; “I stop to stare the moon / Over Battersea full in its diesel-fumed eye”, “the same nice distinctions between half-lies between men half-bought”; “the one / Face in the world that made nothing else matter at all”.

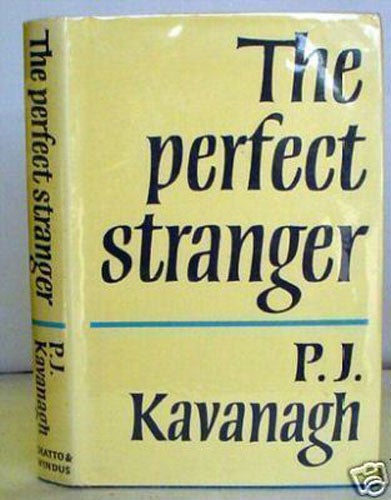

He was above all a great love poet, most famously in his prose memoir The Perfect Stranger, but the poems ‘Perfection Isn’t Like a Perfect Story’, ‘On the Way to the Depot’, The Temperance Billiards Room’, ‘In the Rubber Dinghy’, ‘Commuter’ have the same mood. Poetry is essentially ruminative. Kavanagh knew this and never betrayed it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks