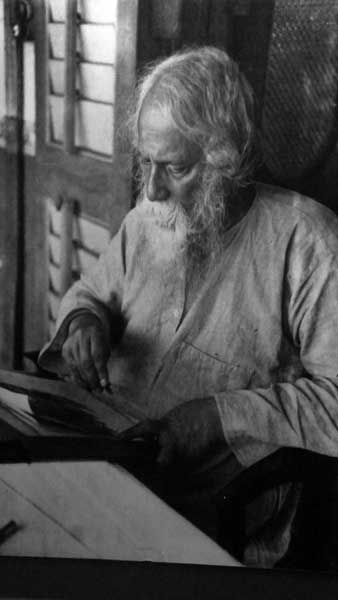

Rabindranath Tagore's legacy lies in the freedom-seeking women of his fiction

Born 150 years ago, Rabindranath Tagore shone as writer, musician and activist to become the Bengali icon.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Romantic poet, song-writer, novelist, nationalist, painter and great idealist, Rabindranath Tagore is, to South Asians, a cultural icon and hero. His 40 volumes of poetry are the emblems of Bengali culture; he is the author of the national anthems of both India and Bangladesh; he was the first Asian winner of a Nobel prize; his institution, Santiniketan, stands today as an enduring and original pedagogical experiment. To those who love him, he is a combination of Shakespeare and the Beatles. His songs are sung in living rooms, on birthdays, and at the turning of every season. He is eternal and symbolic, and his work has spurred, in the generations that have followed, an anxiety of influence that inspires both a visceral terror and a wholehearted, passionate embrace.

My own introduction to Tagore was tinged with a different sort of anxiety - that of the exiled Bengali abroad. In 1977, my father accepted a job with the UN and moved our family to Paris. In our tiny two-room apartment in the 14th arrondissement, my parents took refuge in the reel-to-reel they had brought with them, playing and replaying Tagore classics. Later, they bought a car, and the cassette player was heavy with nostalgia as my father and I made the grey, damp school run every morning.

Tagore was invoked on an almost daily basis. On national holidays, we played the patriotic songs: "I love you, my Golden Bengal"; at the start of the new year, a paean to the season: "come, come o month of Baishakh/ with your hot breath blow away the dying," and on the eve of the monsoon: "the rain clouds are a drum-beat/ rumbling across the heavens." My parents would seek out other exiled compatriots, taking care to identify those who could sing. They hummed: all the time, as if to ward off the knowledge that they had ever left home.

Rabindranath Tagore was born on 7 May 1861, the youngest of 14 children, to a wealthy and socially prominent family in Bengal. His father, brothers, and sisters were activists, artists and writers. He began writing poetry at the age of ten and by the time he died in 1941, left behind a vast canon of literature: poems, songs, plays, letters, and essays that reveal a dynamic, often contradictory set of concerns. A new anthology, The Essential Tagore (Harvard, £29.95), attempts to introduce the reader to a representative sample of Tagore's oeuvre, though its editors Fakrul Alam and Radha Chakravarty warn against the impossibility of finding "the essential quality of a writer so versatile, mercurial, dynamic, and self-contradictory".

During his lifetime, Tagore was celebrated within Bengal as a nationalist, and globally as a sage and source of mystical eastern wisdom. He defied both categories. Though he argued fiercely against the bonds of colonialism, he warned against the excesses of nationalism: "the idea of the nation is one of the most powerful anesthetics that man has invented." And though his poems are full of references to the universal divine, he warned against the divisiveness of organised religion. On this point, he disagreed with that other icon of Indian nationalism, Gandhi, to whom he wrote in 1933: "it is needless to say that I do not at all relish the idea of divinity being enclosed in a brick and mortar temple for the special purpose of exploitation by a particular group of people."

But for Bengali speakers, Tagore's enduring legacy is both nationalist and spiritual, nowhere better expressed than in the songs, of which there are over 5,000. Growing up in Paris, I came to realise that the magnetic pull of Tagore's music had a specific political history. Bengalis on both sides of the border - in the West Bengal region of India, and in Bangladesh - claim Tagore as uniquely theirs. In Bangladesh, this claim is bolstered by the fact that the nationalist revolution did not just include Tagore; it centered on him.

In 1967, when Bangladesh was still known as East Pakistan, the authorities declared a ban on playing Tagore on the state-run radio, arguing that his music went against the values of Pakistan. Overnight, Tagore's poetry and music became the emblems of the separatist movement, his songs sung in protest at every rally and meeting. During that time, and through the independence movement that followed, the love he displayed for Bengal was a protest against the colonising force of Pakistan, and Islam. It is at this moment that Tagore's patriotic songs - those he wrote in protest against the British - really came into their own.

This is why my parents forced Tagore upon me throughout my childhood: because Tagore was the soundtrack of their revolution; because they had heard him broadcast over the Free Bangladesh radio while they resisted the occupying army. Nonetheless, the songs are difficult to translate, and can feel unfamiliar to anyone who has not grown up hearing their circular, lilting melodies.

Now, 150 years since Tagore's birth, it is important to ask in what ways he is still relevant to a global audience. In the early 20th century, when Tagore achieved literary stardom, a Nobel Prize and a knighthood (which he returned in 1919, in protest at the Amritsar massacre), it was primarily through his poetry and spiritualism. Today, it is the short stories that make him enduringly germane. In particular, in Tagore's hands, women are complex, misunderstood characters who fall and fail under the heavy hand of tradition. Their sensibilities are thoroughly modern, even as they strain under the triple weight of poverty, patriarchy and colonialism. The stories are sharp and satirical, and build to unflinching crescendos of tragedy.

The stories, written between 1890 and 1901, stem from Tagore's decade in Shelidah, East Bengal, where he was sent to manage the family estate. On the banks of the Padma river, living in a family houseboat, he developed an intense passion for rural Bengal. "In true knowledge there is love," he wrote, "the heartfelt love with which I have observed village life has opened the door for me... few writers have looked at their country with as much feeling as I have." His time on the banks of the Padma are not only captured in the short stories, but immortalised in a series of letters to his niece, Indrani Devi, in his poetry and his nationalist politics, all of which stem from a deep love of the rural heartland.

Perhaps Tagore's most subtle portrayal of a woman is in the novella "Nashtanir", The Broken Nest. A new translation by Anurava Sinha (Random House India) brings out the simple, unadorned brilliance of this ill-fated love story. Neglected by her husband, Charulata roams her vast household in solitude, until she discovers a companion in her brother-in-law: "in this affluent household, Charu did not have to do anything for anyone, barring Amal, who never rested without making her do something for him. These small labors of love kept her heart alive and fulfilled."

The love between Amal and Charulata, born out of alienation, thrives because of a shared interest in language. They write and read aloud to one another, until both are published (the novella captures the vibrant literary scene of Bengal at the time). This is when their friendship flounders, unable to survive this new public space: "now that he had a taste of acclaim from more than one person, it would make no difference to him if one of those people were to go away."

Their romance is doomed - not, as one would expect, because of its impossibility, but because neither can accommodate the other's passion for a world outside the one they have created together. Charulata is by turn petulant, desperate, conniving and jubilant, a disco-ball of emotions as she passes from infatuation, to love, and finally renunciation.

When Charulata's husband, Bhupati, realises his wife is in love with Amal, he regards her with a detached sympathy: "poor helpless girl, poor sad girl". But despite Bhupati's soft approach, Tagore will not allow for a reconciliation and happy ending. Bhupati decides to forgive Charu, but she refuses, replying to his offer of togetherness, with one simple word, "thak": never mind. Even Satyajit Ray, the Bengali film-maker who put so many of Tagore's stories on screen, flinched from such a harsh ending. In the last scene of his adaptation, the camera catches Charu and Bhupati reaching their hands towards one another.

"Punishment" takes the symbol of female resistance one step further. It tells the story of two brothers, tenant farmers Dukhiram and Chidam Rui. When Dukhiram kills his wife in a fit of rage, Chidam persuades his wife Chandara to take the blame. "If I lose my wife I can get another, but if my brother is hanged, how can I replace him?" He tells Chandara that she must plead self-defence, but when she appears in court, she tells the judge she was unprovoked, and is sentenced to death. In choosing her own fate, Chandara punishes her husband for placing his filial bond to Dukhiram over his romantic attachment to her. "In her thoughts, Chandara was saying to her husband, 'I shall give my youth to the gallows instead of you. My final ties in this life will be to them'". When Chidam tries to visit her on the eve of her execution, she pronounces, "To hell with him!"

There are many more contrary, shape-shifting female characters: in "Chitrangoda", the mythic princess who is brought up as a son to rule the kingdom of Manipur falls in love with the great warrior Arjun and begs God to transform her into a feminine beauty. But after days of idyllic lovemaking, her beloved, hearing of a distant land in which a woman is warrior-princess, longs for his equal. In the end, Chitrangoda declares herself thus: "I am Chitrangoda. Neither goddess nor servant am I. If you let me stand by your side at your darkest hour, let me be the friend of your soul, let me share in your joys and sorrows, only then shall you know me."

In my novel, there is a character whose brother is slowly becoming a religious fundamentalist. She tries in every way she can to remind him of his life before he found his faith, and finally, as he begins to pack away his western clothes and books, she decides the only thing to do is sing to him. She sits outside his bedroom door and plays the Tagore songs they have loved since childhood. She holds up those words - patriotic, pastoral, devotional - against the narrowing of his mind. And that, ultimately, is Tagore's lasting legacy: a raised hand against all forms of rigidity, a love of country that is born out of its landscape and seasons; and a spiritual universe that encompasses a plurality of forms.

Tahmima Anam's new novel, 'The Good Muslim', is published this month by Canongate

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments