Poetry doesn't need to be easier, Mr Paxman – it's up to us to try harder

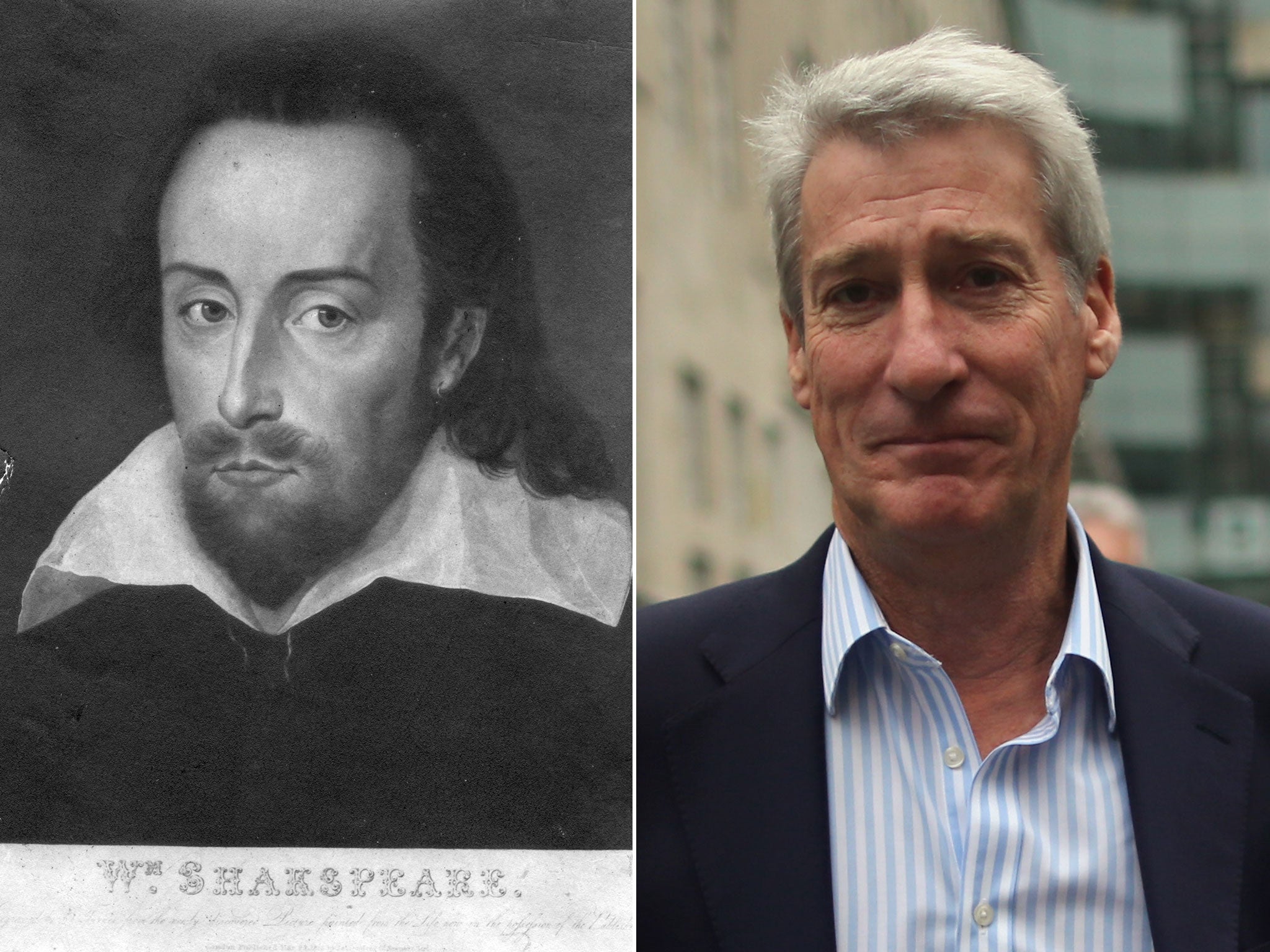

Jeremy Paxman believes poets should make more effort to engage the public. But, says Memphis Barker, poetry shouldn't be easier

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was guilt as much as Shakespeare that brought me to a seat in the Royal Festival Hall on Sunday afternoon. A binge was in the offing. More poetry than you could probably swallow. Four hours of the sweet stuff. Every single one of Shakespeare's sonnets read out one after the other, rat-a-tat-tat.

I hadn't got around to reading them at university, when I had the time to spare, nor touched a book of poetry in the close to three years since leaving. Here was redemption. A total of 154 poems in the tank. Enough to get you through at least another three years.

"You know what you should read," I would now be able to say, if backed into a corner. "Try Sonnet 40 – it's been hideously overlooked. I'm afraid I couldn't quote you a line, you see they all came so thick and fast at this extraordinary reading I went to at…" The perfect hit and run. The poetry get-out clause. Move the conversation swiftly on to the Festival Hall audience. (One woman sitting near me fell asleep by Sonnet 18, "Shall I compare thee…", and proceeded to snore along in gentle accompaniment.)

Shakespeare the poet. Hard not to like him. In a flash of braggadocio, Will (and it is Will writing – not, I feel, a dramatis personae) swears to his love (a man) that, "Not marble, nor the gilded monuments / Of princes, shall outlive this powerful rhyme".

The sonnets are almost half a millennium old and can nearly fill a 2,500 seat auditorium on a June evening, so on that score, the jury has probably retired.

It is Shakespeare's modern successors – in poetry, not so much in plays – who have to front up to the firing squad of public opinion. Would the top 10 poets alive today attract half so many listeners if they gave a reading at the Festival Hall?

It's a puckish question, but Paxman started it. Or at least, he has stepped into the steel-toed boots of a succession of commentators who have sought to administer a good shinning to modern poetry. It doesn't speak to ordinary people any more, says Paxo, who has perfected the art of badgering politicians in simple English. (Can you imagine Cameron or Miliband carrying around a collection of verse? They'd be laughed out of town – is there anything you can fit in your pocket that is more out-of-touch, elitist, and non-normal? An aubergine?)

Blaming the poets for their shrimpy readership is an old game. But I'm not 100 per cent inclined to disagree with Paxman when he says poets appear to write for each other. Some writers seem to overly relish an intellectual arm-wrestle.

Geoffrey Hill – often called the greatest living poet working in English – has, in recent collections, apparently been engaged in an attempt to shake the last reader off his tail. Paul Muldoon sometimes gives the impression his ideal audience would be a collection of footnotes.

Then again, much of what both these poets write is brain-spritzingly exciting, if you put in the effort (in the right collection). And the point Paxman seems to miss is that effort is always required, even with less abstruse poets: Don Paterson, Rosemary Tonks, Kay Ryan etc.

All of these writers can speak very plainly indeed. But that's not the right way to judge them. Poetry isn't advertising. You don't always have to get it. Or at least not straight away. The reason not so many people try any more is the pleasure's a hard one, and a slow one, and we tend to go for the opposite – except in dire straits of love or grief.

And of course, these writers aren't as good as Shakespeare. But one other thing I'd say is that, after four hours of him, you start to crave some new imagery (he's working with 16th-century materials). A bit of neon, or plastic. You can't be wholly sated by the poetry of the past.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments