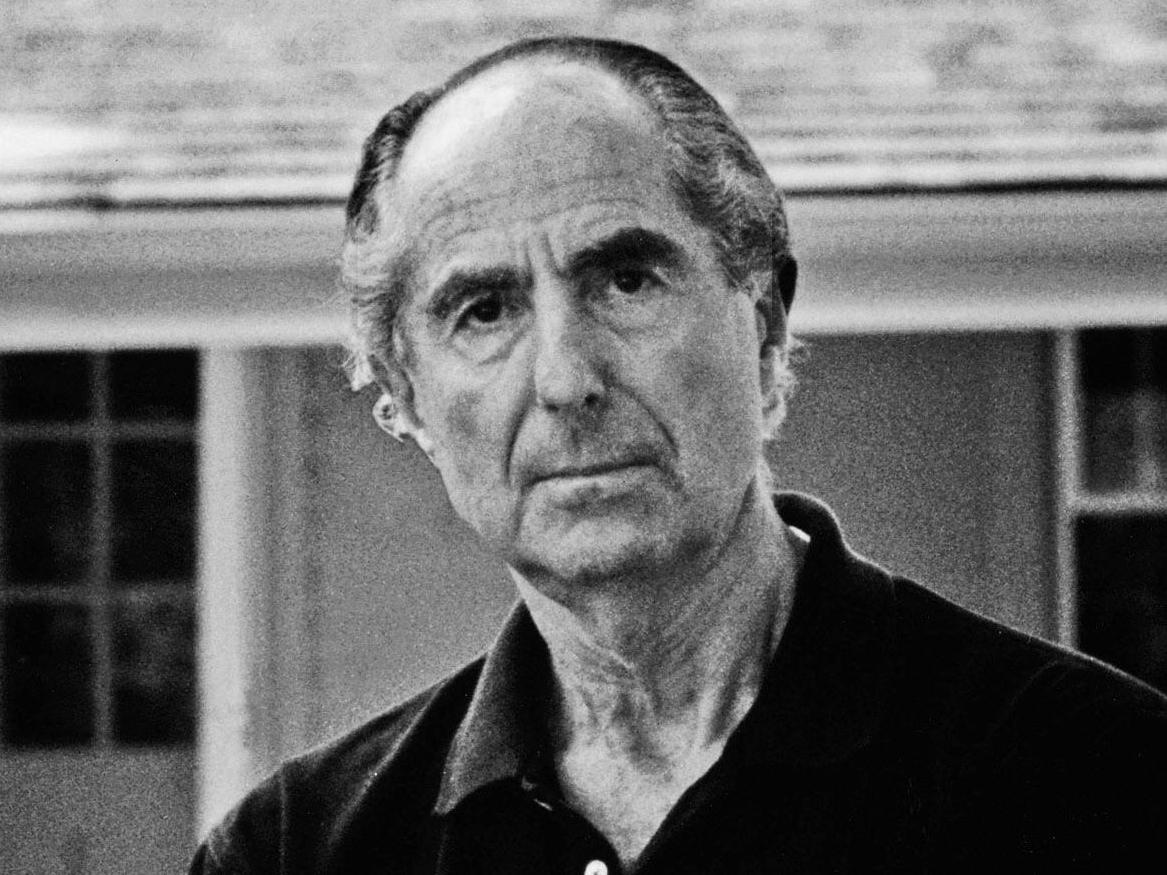

How Philip Roth's Portnoy's Complaint shocked America

Late novelist stunned readers in 1969 with novel centred around frank sexual confessions and neurosis of New Jersey lawyer Alexander Portnoy, the 'Raskolnikov of jerking off'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Philip Roth was one of the most admired writers of the post-war era. Perhaps most widely read for his late period masterpieces American Pastoral (1997), The Human Stain (2000) and The Plot Against America (2004), Roth remains notorious for a much earlier novel, Portnoy’s Complaint (1969).

A comic monologue in which New Jersey lawyer and “lust-ridden, mother addicted young Jewish bachelor” Alexander Portnoy recounts his complete sexual history to psychoanalyst Dr Spielvogel, the book was described as a “wild blue shocker” by Life magazine and caused outrage for its uproarious depiction of frenzied teenage masturbation.

An early chapter, “Whacking Off”, recounts Portnoy’s turf war with his terminally constipated father for occupation of the toilet in hilarious, vigorous detail:

“Then came adolescence – half my waking life spent locked behind the bathroom door, firing my wad down the toilet bowl, or into the laundry hamper, or splat, up against the medicine-chest mirror, before which I stood in my dropped drawers so I could see how it looked coming out. Or else I was doubled over my flying fist, eyes pressed close but mouth wide open...”

You get the idea. The passage goes on to describe Portnoy’s deranged fantasies as he violates unwashed socks, his sister’s underwear, a cored apple, an empty milk bottle, a baseball mitt and, most famously, “the maddened piece of liver that, in my own insanity, I bought one afternoon at a butcher shop and, believe it or not, violated behind a billboard on the way to a bar mitzvah lesson”.

An extraordinary feat of creative writing on a taboo subject, it’s hard to imagine Larry David writing “The Contest” episode of Seinfeld in 1992 without it. The joke there is of course that Jerry, George, Elaine and Kramer go out of their way to avoid saying the word “masturbation”, coining the coy euphemism “master of my domain” instead, whereas Roth’s prose is packed with wild leaps of language to describe Portnoy’s primary hobby.

Having previously been praised for his short story collection Goodbye, Columbus (1959), Roth realised he had a hit on his hands and took his parents out for lunch to warn them about his new work’s explicit content. His mother Bess told him he had “delusions of grandeur” and worried: “He’s going to have his heart broken because this is not going to happen.”

She need not have fretted, however. Portnoy arrived at a moment when New York Jewish comics like Woody Allen and Lenny Bruce were rewriting the rules of stand-up and “one of the dirtiest books ever published” (The New Yorker), born out of the author’s well-practised dinner party routines, likewise captured the voice of second generation Jews magnificently.

The cruellest thing anyone can do with Portnoy’s Complaint is to read it twice

Less concerned with the burden of history than older writers such as Saul Bellow or Bernard Malamud or recent immigrants from Europe like Isaac Bashevis Singer, these young men arrived at the close of a tumultuous decade to voice the anxieties and priorities of nebbish kids growing up in the 1950s. They were keen to assimilate and impress girls but weighed down by the hectoring, emotional blackmail and old world expectations of their parents.

Or, as Alexander Portnoy expresses the inner turmoil: “Enough being a nice Jewish boy, publicly pleasing my parents while privately pulling my putz!”

As Roth later recalled: “I got literary fame ... I got sexual fame and I also got mad man fame. I got hundreds of letters, 100 a week, some of them letters with pictures of girls in bikinis. I had lots of opportunity to ruin my life.”

Portnoy’s Complaint was also roundly condemned as blasphemous and profane, with Israeli scholar Gershom Scholem going so far as to call it “the book for which all anti-Semites have been praying”. Some Jews were wary of the sudden fashion for Jewish comedy among American gentiles at the time and feared that unhelpful stereotypes of the “schlemiel” (perennial victim) or “schnorrer” (sponger) risked becoming embedded in the culture.

Portnoy, “the Raskolnikov of jerking off”, might perpetuate a vision of Jewish lechery, some feared, while his lack of moral seriousness and flippant attitude towards psychiatry (”Let’s put the id back in the yid!”) were disrespectful.

Critic Irving Howe meanwhile damned the novel’s tactics on formal grounds: “The cruellest thing anyone can do with Portnoy’s Complaint is to read it twice”.

Bernard Avishai’s 2012 book Promiscuous has more recently argued that Roth’s novel deserves to be remembered as an assault on “bourgeois liberty” as radical as Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (1953), an attack on the American middle-class rather than on Jews as “poster-children for... restraint and public decorum”. Portnoy himself proclaims that, “through f***ing I will discover America”.

The novel’s impact was nevertheless huge and its author’s fame grew throughout the 1970s.

Roth took inspiration from Nikolai Gogol’s surreal short story “The Nose” for his novella The Breast in 1972 – about a man who wakes up one morning to find himself transformed into a 155-pound tit – and channelled his concerns through a series of novels starring his fictional alter ego Nathan Zuckerman, beginning with The Ghost Writer in 1979.

His own favourite among his novels was Sabbath’s Theatre (1995), which revisited the shock territory of Portnoy when its priapic puppeteer, protagonist Mickey Sabbath, masturbates into his dead lover’s grave. Roth relished the “hate” the work attracted.

“I think it’s got a lot of freedom in it,” he said of that novel at a gathering of the Television Critics Association in Los Angeles in January 2013. “That’s what you’re looking for as a writer when you’re working. You’re looking for your own freedom. To lose your inhibition to delve deep into your memory and experiences and life and then to find the prose that will persuade the reader.”

Booker Prize-winning novelist and former Independent columnist Howard Jacobson, often dubbed “the British Philip Roth”, has spoken of the jealousy he experiences when hearing his wife’s laughter in another room as she reads Roth, feeling cuckolded by the author’s ability to bring pleasure to the woman he loves.

Writing in 2016, Mr Jacobson said of his literary hero: “Roth, of course, has always been a novelist who gives his readers a wild ride. If you haven’t wrestled with the angel and the devil and lost to both, you can’t be said to have read him. The nakedness of the encounter is part of what makes him the greatest novelist alive.”

The popular image of Roth has perhaps been set in stone by Alex Ross Perry’s 2014 film Listen Up Philip, in which Jonathan Pryce played arrogant novelist Ike Zimmerman, based on the celebrated writer.

Roth had announced his retirement in November 2012, telling French magazine Les Inrockuptibles, ”I’m done”. He subsequently spent his time drinking orange juice in bed and re-reading his works in order, from most recent to earliest.

Quoting boxer Joe Louis, he concluded: “I did the best I could with what I had.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments