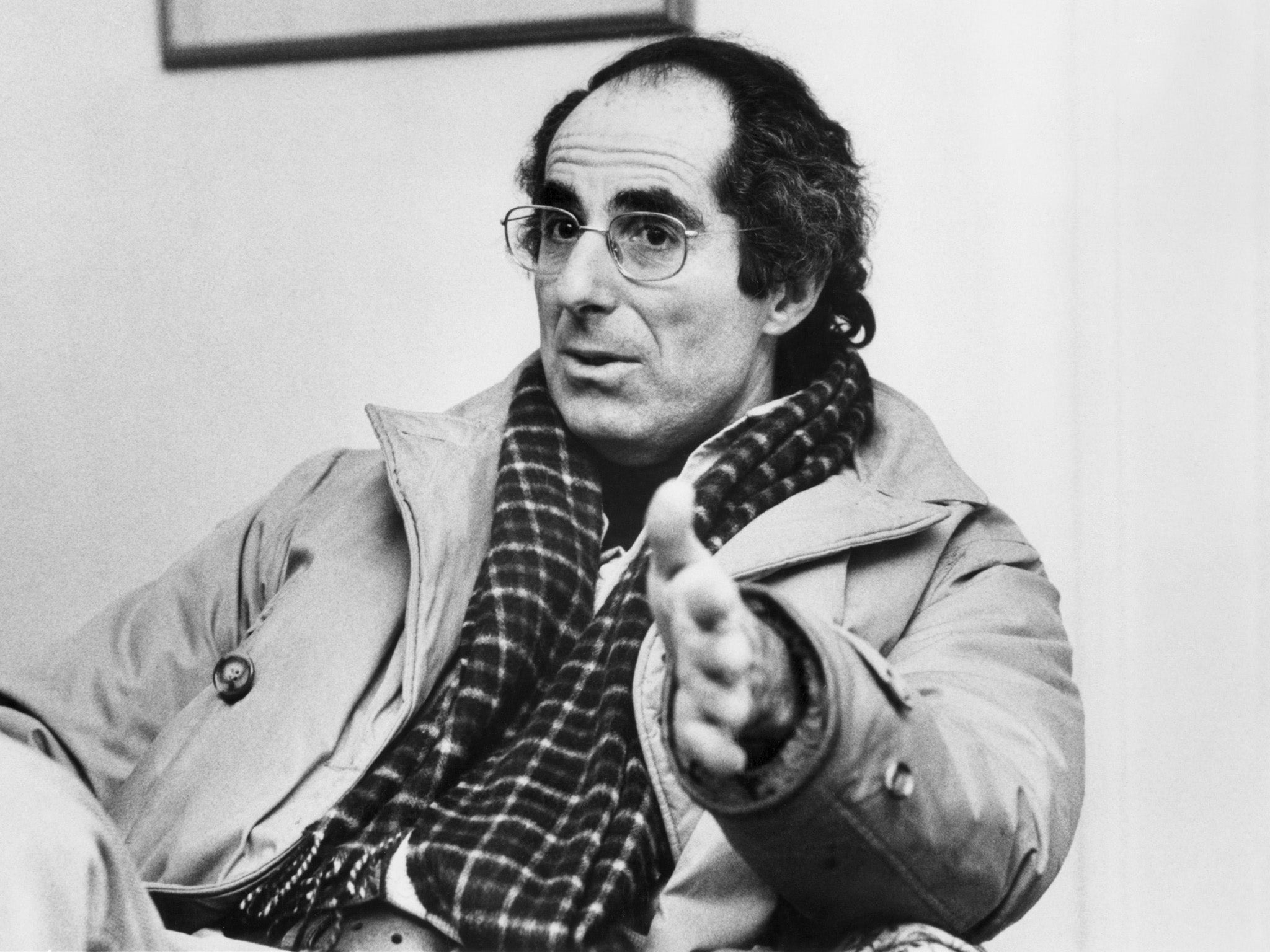

To Philip Roth, writing was as natural as breathing

The Jewish-American satirist was an immaculate writer with a ‘resistance to plaintive metaphor and poeticised analogy’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

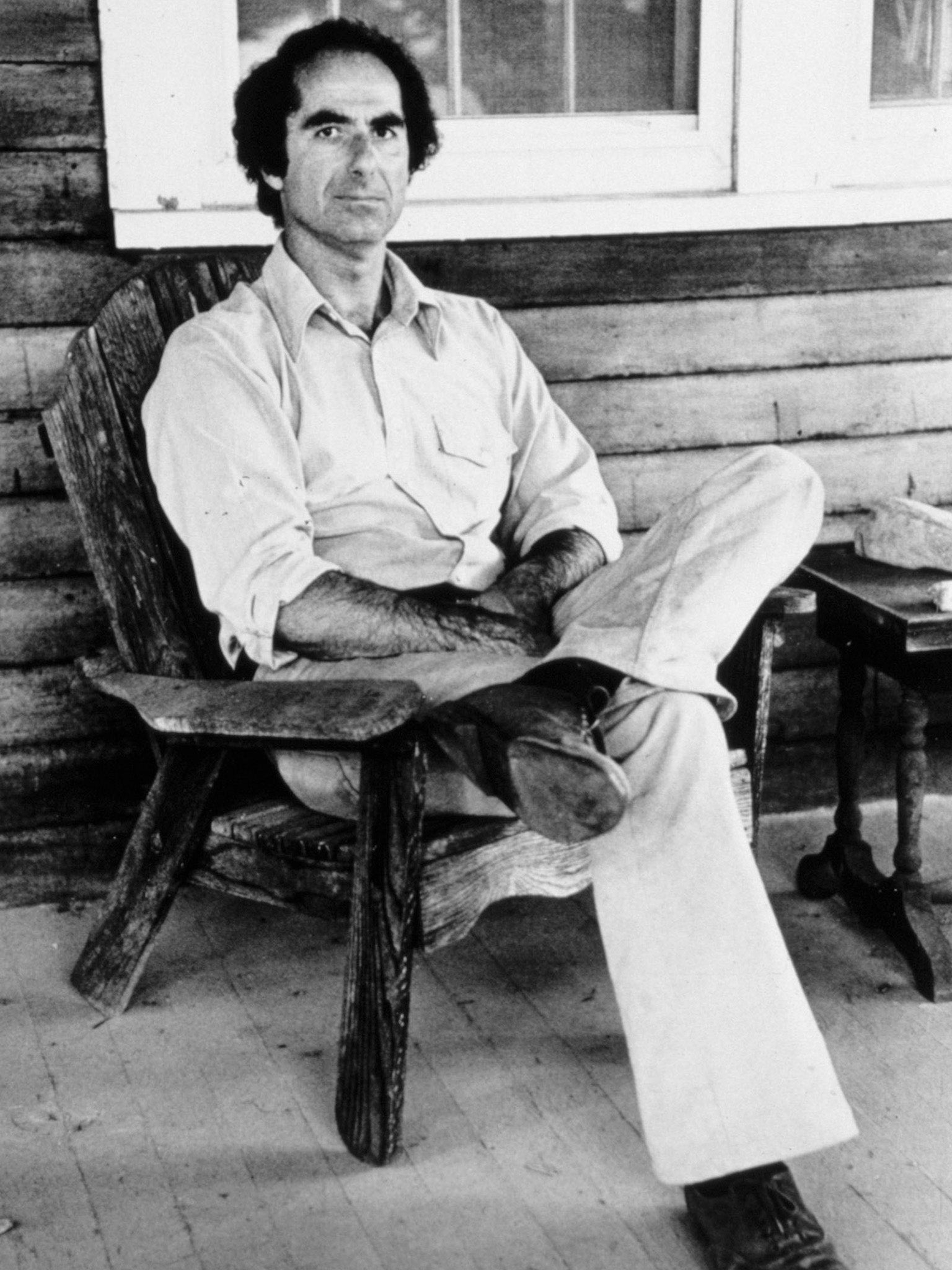

Your support makes all the difference.He wrote standing up. He paced around as he thought. He once said he walked half a mile for every page he wrote. And with Roth’s astonishing body of work, that’s a lot of walking.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning author of more than 30 books combined energy, athleticism and intellect in a way few if any other authors have. His fiction chronicled America, particularly Jewish America. He didn’t always like being so described, feeling it was an appreciation that was limiting. But no one did it better.

While appreciations must rightly concentrate on his prose, his leaping imagination, and the extraordinary prescience of his novels be it in matters of politics or race, the personal too cannot be ignored.

His second wife, the actress Claire Bloom, wrote fulsomely in her autobiography of their first meeting: “Tanned, tall and lean, he was unusually handsome; he also seemed to be well aware of his startling effect on women.”

She wrote less fulsomely of his decision that he would not share a home with Bloom’s daughter, his “mixture of kindness and cruelty, generosity and selfishness” and how that tanned attractive face was to become “feral, unflinching, hostile, accusative”.

She described him as depressed and verbally abusive, adding that he had insisted on a prenuptial agreement, saying he could terminate the marriage at will with no further responsibility to his wife and all possessions would revert back to him. Bloom’s divorce lawyer told her was the most brutal document of its kind he had ever encountered.

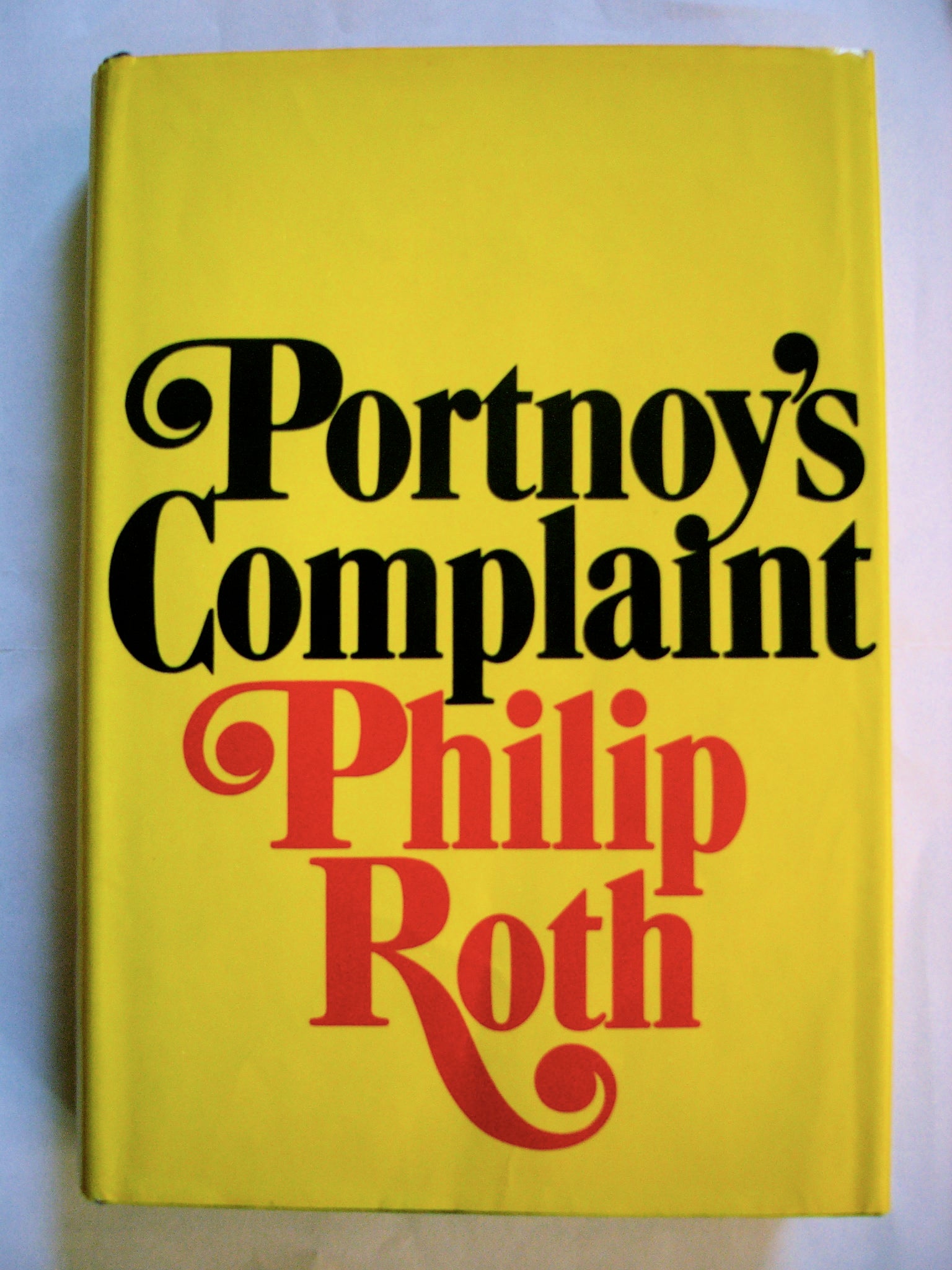

But, separate the art and the artist (if one’s still allowed to). The art came to international attention in 1969 with Portnoy’s Complaint. It may be a slightly exaggerated view of recent history to maintain, as many do now, that it scandalised America with its concentration on sex, largely as comedy, and a young hero with a penchant for (graphically described) masturbation.

Open discussion of sex was not exactly unknown in the late Sixties, nor had it been unknown in literature. Nevertheless, Roth himself remarked that it had helped give him a “reputation as a crazed penis”.

More probably it scandalised Jewish America, and certainly the rabbis who had denounced his earlier story Goodbye Columbus as the work of “a self-hating Jew”.

But Roth, who grew up in Newark, New Jersey, was right that seeing him in any way as the voice of one community was absurdly limiting. What he brought to the art form from his earliest works was literature that explored, with humour and with anxiety, the American psyche.

One must consider too, with some awe, another word that is routinely used about Roth: his prescience. The Plot against America imagined that a huge, wealthy, right-wing celebrity, the aviator Charles Lindbergh, became president and waged a war against the Jews. A celebrity, with well-defined prejudices, becoming president of the United States! It could never happen in real life, of course.

The writer Al Alvarez, who knew Roth, wrote: “Style, in the formal, flowery sense, bores him; he has, he once wrote, ‘a resistance to plaintive metaphor and poeticised analogy’.

“His prose is immaculate yet curiously plain and unostentatious, as natural as breathing. Reading him, it’s always the story that’s in your face, never the style.”

Indeed, that is what distinguished him from so many of his contemporaries on both sides of the Atlantic.

That, and the stories, sometimes dealing with the neuroses and complexities of the modern Jewish-American experience, sometimes with the sexual difficulties of middle age, but more often with a disillusion with the American dream and its fading since the Thirties and Forties: the decades that produced the years of maturity of his parents’ generation.

And, of course, his novels dealt with the existential difficulties of life itself. They were told through a comic lens, mixed with searing pain. His literary device of recurring narrators and alter egos, even on occasion named Philip Roth, tempted the reader to feel they were getting closer to the author, only to be continually disabused.

Sex continued to be one, though by no means the sole, preoccupation of Roth’s writing. Martin Amis once said he flicked through 1995’s Sabbath’s Theater “looking for the clean bits”.

In fact the book was more a raging against death, subject matter that probably concerned him from his fifties onwards. The book can be singled out for its memorable final words: “How could he leave? How could he go? Everything he hated was here.”

1997’s American Pastoral, thought by many to be his greatest book, concerns a Newark businessman and athlete whose life is destroyed when his teenage daughter becomes a terrorist. The book turns into an elegy for those disappearing dreams of civic order and domestic happiness.

But, for me, 2000’s The Human Stain, with one of the greatest twists in the literary canon, exploring race and the state of America as it approached a new millennium, has few challengers.

Anticipating the political correctness and new puritanism which would take no prisoners, Roth writes of a university professor whose career is ended and life destroyed when he is wrongly accused of racism. It is played out to the background of an America in a rage of prurience over revelations about President Clinton. It’s a wondrous mix of tension, comedy, suspense, shock and insight into social mores that were in a frenzy of confusion.

After more than 50 years as a writer, Roth decided that 2010’s Nemesis, the story of a polio epidemic in the Newark, New Jersey neighbourhood where he grew up, would be his last novel.

In one of his final interviews, just this year with The New York Times, Roth reflected on his 50-plus years as a writer, describing it as: “Exhilaration and groaning. Frustration and freedom. Inspiration and uncertainty. Abundance and emptiness. Blazing forth and muddling through.”

Certainly, for the reader the work blazed, both illuminating and casting a dark shadow over life in the second half of the 20th century and beyond, making its author not just the greatest chronicler of American life through his fiction, but one of the greatest novelists of the 20th century.

David Lister is the former arts editor of The Independent

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments