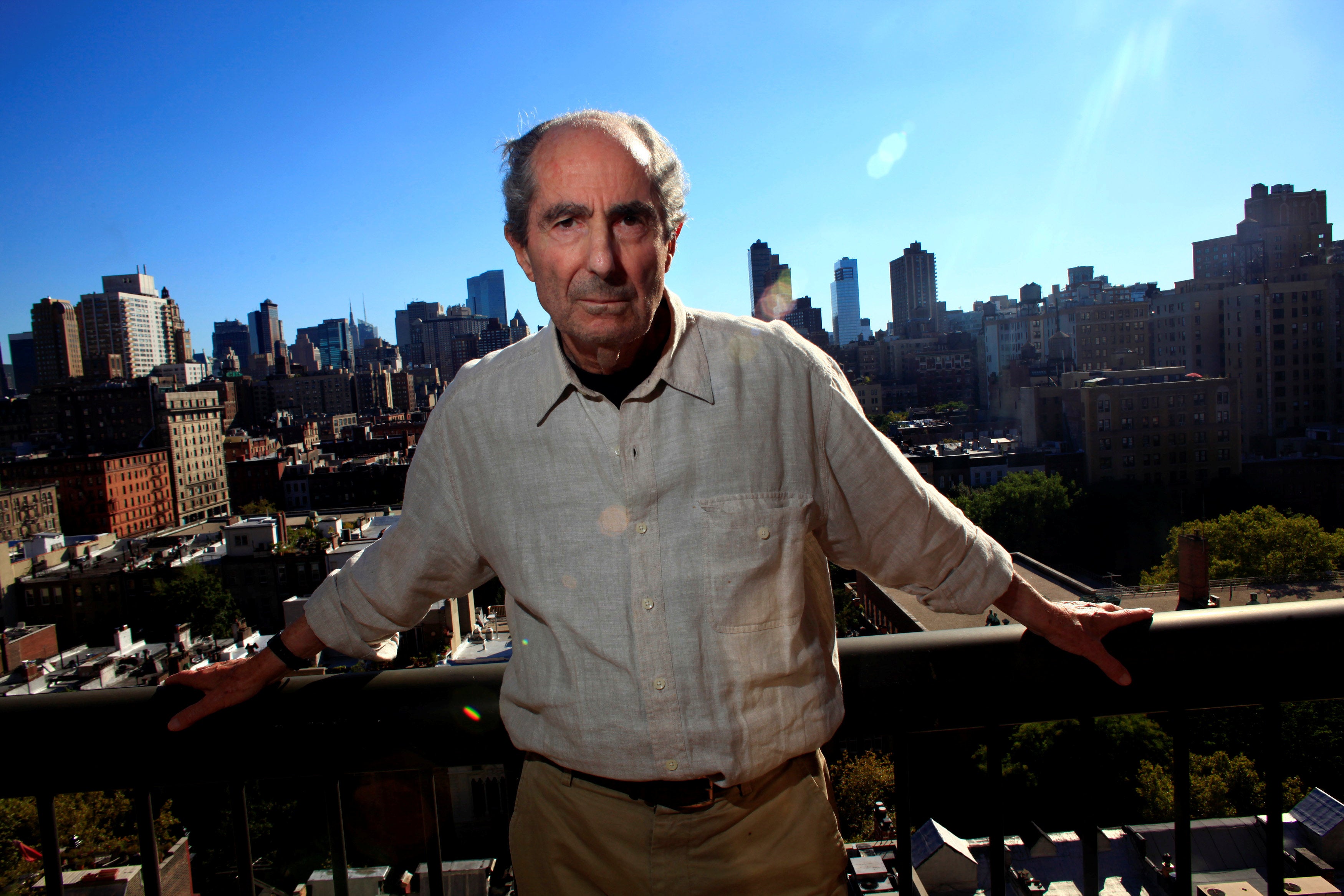

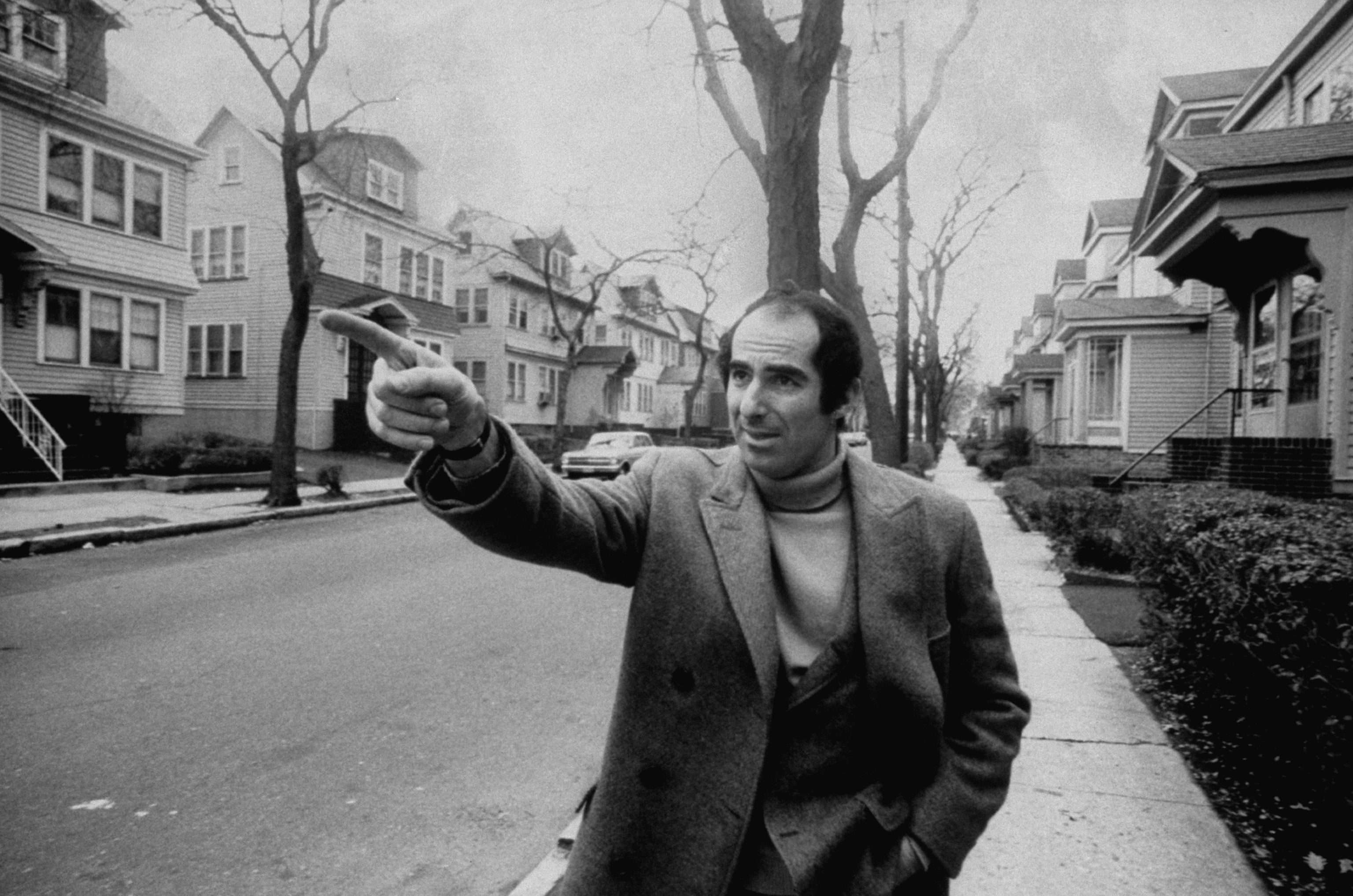

‘It will probably stain his name’: What happens to Philip Roth’s reputation now?

Blake Bailey was given unique access to the late Philip Roth’s archive, but his biography was pulled from publication and Bailey was dropped as allegations of sexual assault were made against him. So, what now for Roth’s legacy? By Alexandra Alter and Jennifer Schuessler

Late in his life, Philip Roth occasionally joked that he had two great calamities ahead of him: death and a biography.

“Let’s hope the first comes first,” he said in a 2013 interview.

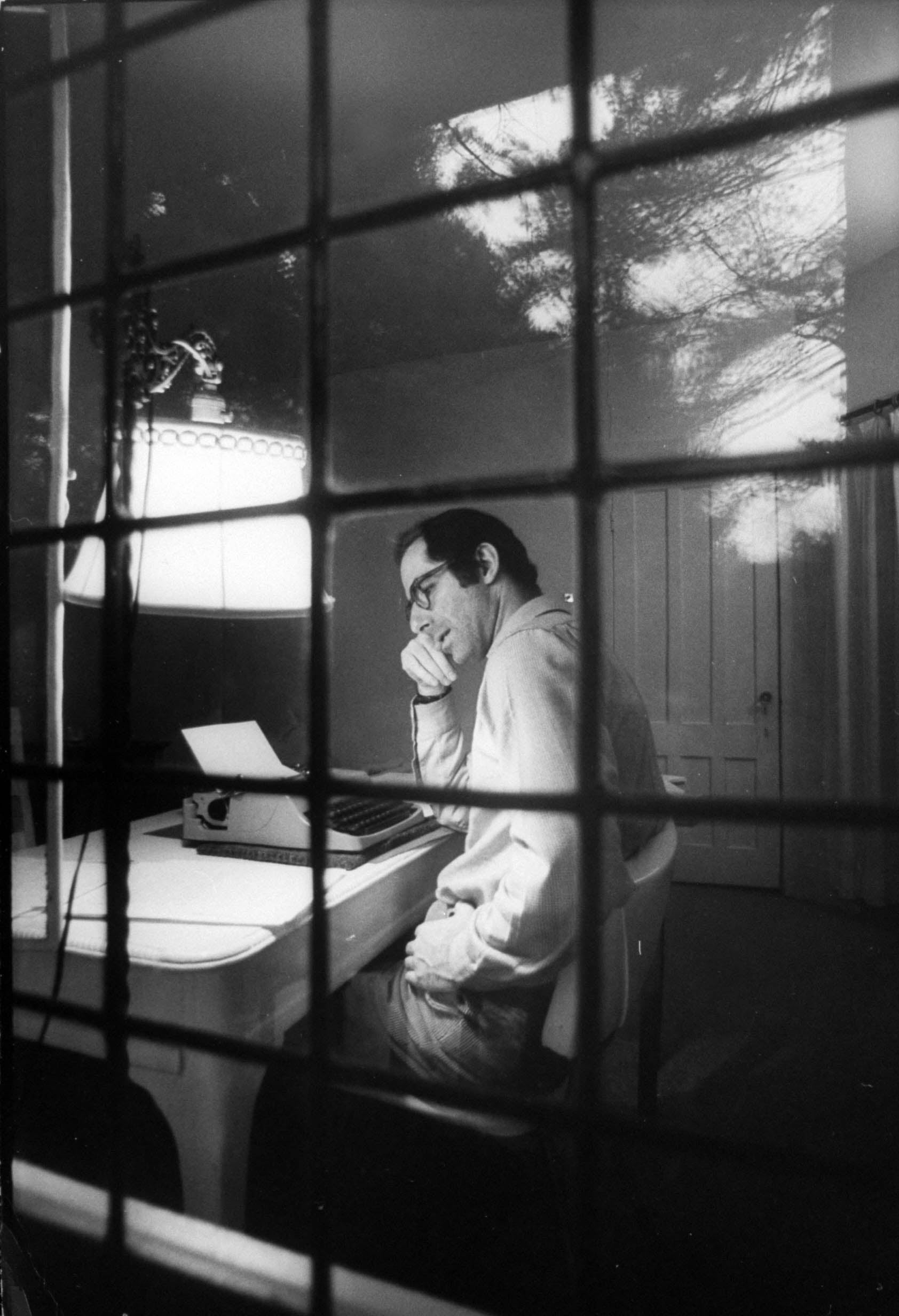

Roth, the author of American Pastoral, Portnoy’s Complaint and 29 other books, didn’t live to read the biography that he authorised Blake Bailey to write. But he went to enormous lengths to shape his literary legacy. In the years leading up to his death in 2018, Roth sat for hundreds of hours of interviews and conversations with Bailey. He also gave him exclusive access to a treasure trove of documents and unpublished writing – a richly detailed, intimate road map that Roth hoped would inform the definitive account of his life.

But Roth’s efforts to control his posthumous reputation may have backfired. In April, weeks after the publication of Bailey’s book, several women accused Bailey of sexual misconduct and assault, leading his publisher, WW Norton, to halt shipments and then take the biography out of print. (Bailey has denied the allegations.) In May, an independent US publisher, Skyhorse, acquired the book and announced plans to release it in paperback.

While Bailey has found a new publisher, his Roth biography is now inextricably linked to controversy. The accusations he now faces have intensified a parallel conversation about Roth’s treatment of women, adding fuel to the questions of whether Bailey’s account of Roth’s sexual and romantic relationships was overly sympathetic and oversimplified.

Scholars and writers are concerned that nobody else will have access to the personal papers that Bailey was able to read and draw from

Several of Roth’s friends say they are distressed by the way the controversy around Bailey has spread from author to subject.

“It’s a shame for Philip that he has to be associated with what occurred,” says Joel Conarroe, a writer, decades-long friend of Roth’s and his former executor. “What troubles some of us is that this affects Philip’s reputation.”

Other acquaintances expressed disappointment that Roth’s authorised biography focused so heavily on his private life and less on his fiction.

“It will probably stain his name, sadly, for some time to come,” says Claudia Roth Pierpont, a friend of Roth’s (they are not related) and the author of Roth Unbound, a 2013 study of his books that drew on their extensive conversations. “We’d love to have a good biography of Philip Roth that was responsible and took in things that I’m not sure the Blake Bailey biography took in anyway.”

Some who were close to Roth say the book missed the mark in more specific ways. Caro Llewellyn, a writer who met Roth at John Updike’s 2009 memorial service, says Bailey misrepresented her platonic friendship with Roth.

In the biography, Bailey identifies her by the pseudonym Mona. He describes how she and Roth were attracted to each other and were physically intimate but never had sex because he was unable to, even after taking Viagra. But Llewellyn says the scene Bailey described never occurred.

“Philip and I never fooled around,” says Llewellyn, who wrote about her relationship with Roth in her 2019 memoir, Diving Into Glass.

Llewellyn – who declined to be interviewed by Bailey – says she was more upset by what was left out of the biography, which gives the impression that she was a marginal figure in Roth’s life, a fling that didn’t work out.

“My intimacy with Philip didn’t conform to the story Blake was trying to write,” she says.

In an email, Bailey says that he based the description of their relationship on information from Roth, who “tended to be truthful”, adding that “the information was harmless enough, and besides, her identity was protected by a pseudonym.” He disputes the critique that his book was overly focused on Roth’s intimate relationships and diminished the women in his life.

Bailey’s book will not be the last word. In addition to an unauthorised biography by literary critic Ira Nadel that came out in March, there are more books on the way, including a biography by Stanford University professor Steven Zipperstein, and The Philip Roth We Don’t Know, by Jacques Berlinerblau, a Georgetown University professor.

But scholars and writers are concerned that nobody else will have access to the personal papers that Bailey was able to read and draw from. In May, 23 of them released a statement imploring the estate not to destroy the papers, as it has said it might, and to make them “readily available” to researchers.

“A writer of Mr. Roth’s stature deserves multiple accounts of his life in keeping with the nuance and complexity of his art,” the statement says.

“Roth’s work speaks for itself, but it’s always going to be footnoted with the Blake Bailey story,” says Aimee Pozorski, the co-executive editor of the academic journal Philip Roth Studies, who authored the statement with Berlinerblau. “If the estate was committed to protecting his legacy, then more people should have access to these materials to add layers to the conversation, so that it doesn’t stop with the idea that Roth was a misogynist,” she says.

It’s unclear what will become of the material Roth gave to Bailey. Roth provided hundreds of documents, attaching detailed memos explaining the significance of each file. He shared tapes and CDs of interviews conducted by close friends, among them Judith Thurman, Janet Malcolm and Ross Miller, Roth’s first authorised biographer, who worked on a book for years until Roth took him off the project for taking too long and failing to conduct key interviews.

Roth also gave Bailey copies of two unpublished manuscripts, “Notes for My Biographer,” a 295-page rebuttal of his ex-wife Claire Bloom’s 1996 memoir, and “Notes on a Slander-Monger,” a response to the notes and interviews Miller had compiled.

Some of the material will likely go to the Library of Congress, where the bulk of Roth’s archives are already collected. Others, including “Notes for My Biographer”, may never be seen again.

Those who are pushing for access to the material entrusted to Bailey argue that, in someone else’s hands, it could yield very different insights into Roth’s relationship to Judaism, politics, money or illness

In a 2012 interview, Roth said he had asked his literary executors to destroy his private papers after Bailey completed his book.

Julia Golier, one of the executors, told The New York Times Magazine in March that the estate might indeed do that. Since the release of the biography and the ensuing scandal, however, the estate has been quiet. Golier and literary agent Andrew Wylie, a co-executor of the estate, declined to comment on the plans for the papers.

Those who are pushing for access to the material entrusted to Bailey argue that, in someone else’s hands, it could yield very different insights into Roth’s relationship to Judaism, politics, money or illness.

“It’s fundamental material relating to a major American writer,” Nadel says.

The scandal over Bailey’s alleged misconduct involves a tangle of ethical issues, including, for some, whether Norton was justified in withdrawing the book. But the fraught questions around how much writers, or their estates, want others to see are as old as biography itself.

All writers and estates decide what they place in archives, keep for themselves or destroy. It’s not unusual for letters and other personal materials that are placed in archives to be sealed for decades after a person’s death to protect his or her privacy, or someone else’s.

But literary history is also full of moments of betrayal, when trusted confidants defied authors’ wishes. Max Brod disregarded Franz Kafka’s order to burn his unpublished manuscripts and diaries. Vladimir Nabokov and Philip Larkin’s directives to destroy unpublished manuscripts were overridden by heirs and executors, who not only preserved but published them.

It’s unclear what Roth’s actual directives were. And friends have differing opinions about whether the aftermath of his biography’s release would have changed them, though some say they doubt he would have favored the kind of immediate and open access some are calling for.

“It would be for Philip a very nerve-wracking thing to think that just anyone could go rummaging through it and pick out what they wanted,” says one of his close friends, Bernard Avishai.

Judith Thurman, a biographer and staff writer at The New Yorker, says the executors faced an impossible choice.

“We don’t know if he would have given someone else a do-over, and we don’t know what other person he would have chosen,” she says, adding that she opposes the destruction of his personal papers. “I’m against destroying anything.”

Roth was invested in preserving much of his own paper trail. He began giving his papers to the Library of Congress in the 1970s, and the institution has amassed some 25,000 items from 1938 to 2001, including correspondence with Bloom, Updike, Saul Bellow and Cynthia Ozick. After Roth’s death, the library acquired more papers, including correspondence, drafts, research notes, autobiographical notes and other personal effects.

The more recent acquisitions – roughly 15 boxes of material from 1945 to 2018 – can only be viewed with the permission of the Roth estate, until 2050, when the papers will be open to anyone, according to Barbara Bair, the literary specialist in the library’s manuscript division.

“We are hopeful that any additional materials held by Mr Bailey or others will be consolidated at the Library, but specific arrangements have not been finalised,” she says.

Meanwhile, the estate has moved aggressively to control access to Roth materials held independently at Princeton University, which the university purchased in 2018 from Roth’s friend Benjamin Taylor. The cache includes a copy of Notes on a Slander-Monger, unpublished essays on such subjects as money, marriage and illness, and a list of his relationships with women, with commentary.

Normally, access to materials in archives is governed by an agreement with the donor, not the person who created the documents. In 2018, Princeton announced that the collection was open to researchers, but it subsequently closed it and removed the guide to the collection from the internet.

Scholars researching books on Roth were stunned by the abrupt closure. A spokesperson for the university says it is in “ongoing discussions” with the Roth estate regarding the collection.

There’s likely much more Roth material that hasn’t yet surfaced. Several friends of the novelist say he frequently sent them manuscripts and early drafts of novels, documents that could offer insight into how his work evolved.

In 2020, Joel Conarroe sold about 60 Roth letters through the auction house Bonhams. He says he has about 100 additional letters from Roth that he plans to give to an archive or library, possibly the Newark Public Library, where Roth donated his own collection of 7,000 books, many of them annotated. The collection is scheduled to open to the public this month.

Even as scholars worry about the fate of Roth’s private papers, some are optimistic about the future of Roth studies, as more scholars examine his life and work.

“The story is certainly not over,” says Nadel, the author of Philip Roth: A Counterlife. “The archive is growing.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks