Philip Larkin in Westminster Abbey’s Poets' Corner: 'I think there will be a space for me'

After years of scandal, the poet Larkin has finally been memorialised in Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner with a stone bearing his name lying close to other writers he worshipped, including Thomas Hardy and D H Lawrence

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Philip Larkin, one of English poetry’s most recognisable voices, has been memorialised in Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner.

His ledger stone was unveiled last week alongside tombs and memorials commemorating some of the finest writers in English literary history, including Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth, Tennyson, and T S Eliot. The ceremony took place 31 years to the day since Larkin’s death.

This is an occasion foreseen by Larkin himself, whose place in Poets’ Corner would probably have been guaranteed had he accepted the Poet Laureateship in 1984. Larkin was touted for this role as early as 1972; on that occasion it went to John Betjeman, a poet he admired. When Betjeman died in 1984, Larkin was the obvious choice. He didn’t share the public’s enthusiasm, but was reflective about his place in literary history: “I think there will be a space for me,” he told his mother.

Although a household name – a rare thing in poetry – Larkin had spent three decades dodging attention. Reports of the so-called Hermit of Hull’s reclusiveness were exaggerated, but it’s true that he largely avoided public roles – and what role in British poetry is more public, more bardic, than the laureateship? Larkin wasn’t joking when he told one acquaintance: “I just couldn’t face the 50 letters a day, TV show, representing British Poetry in the ’poetry conference at Belgrade’ side of it all.” To Andrew Motion, a later Laureate, he wrote: “Think of the stamps! Think of the stamps!”

Having politely declined, Larkin knew he had gifted Ted Hughes – a poetic rival – a spot in Westminster Abbey. But when Larkin died the year after, he was already known as Britain’s “unofficial Laureate”. One obituary hailed him as “the funniest and most intelligent English writer of the day, and the greatest living poet in our language”. Perhaps the spot unveiled in the Abbey was always his.

But this outcome wasn’t always so certain. Scandal in the 1990s threatened to obliterate Larkin’s reputation. The publication of a Selected Letters in 1992, containing foul-mouthed tirades against women, ethnic minorities, and the working-class, was swiftly followed by Motion’s 1993 biography, which revealed Larkin’s heavy drinking, pornographic habits, and multiple infidelities.

Influential cultural critics rushed to denounce Larkin. Lisa Jardine lambasted his 'Little Englandism', boasting “we don’t tend to teach Larkin much now in my department of English”. Tom Paulin spoke of Larkin’s “quasi-fascism”, and the “distressing and in many ways revolting compilation which imperfectly reveals and conceals the sewer under the national monument Larkin became”.

This was a troubling and hysterical reaction to biographical disclosures. However regrettable, Larkin’s bigotry was performative and insincere; much of his behaviour was also judged against puritanical moral standards. More pernicious was the reinterpretation of his work in the light of these new perceptions of his life. Bizarrely, poems hitherto loved for their humanity were suddenly dismissed as the eruptions of a bitterly prejudiced man.

Assessments today tend to be less extreme, but the way we think about Larkin is still jammed somewhere between celebratory and condemnatory impulses. The Philip Larkin Society has campaigned over many years for a Poets’ Corner memorial, but the previous dean rejected this on the grounds of Larkin’s agnosticism, and an unofficial policy requiring writers to be dead for 20 years.

As neither criterion prevented Hughes from being commemorated in 2011, it’s not unreasonable to wonder whether other anxieties were at play. The current dean expressed a different view: “I have no doubt that his work and memory will live on as long as the English language continues to be understood.” His sentiment wisely refocuses attention on what matters most: the poetry.

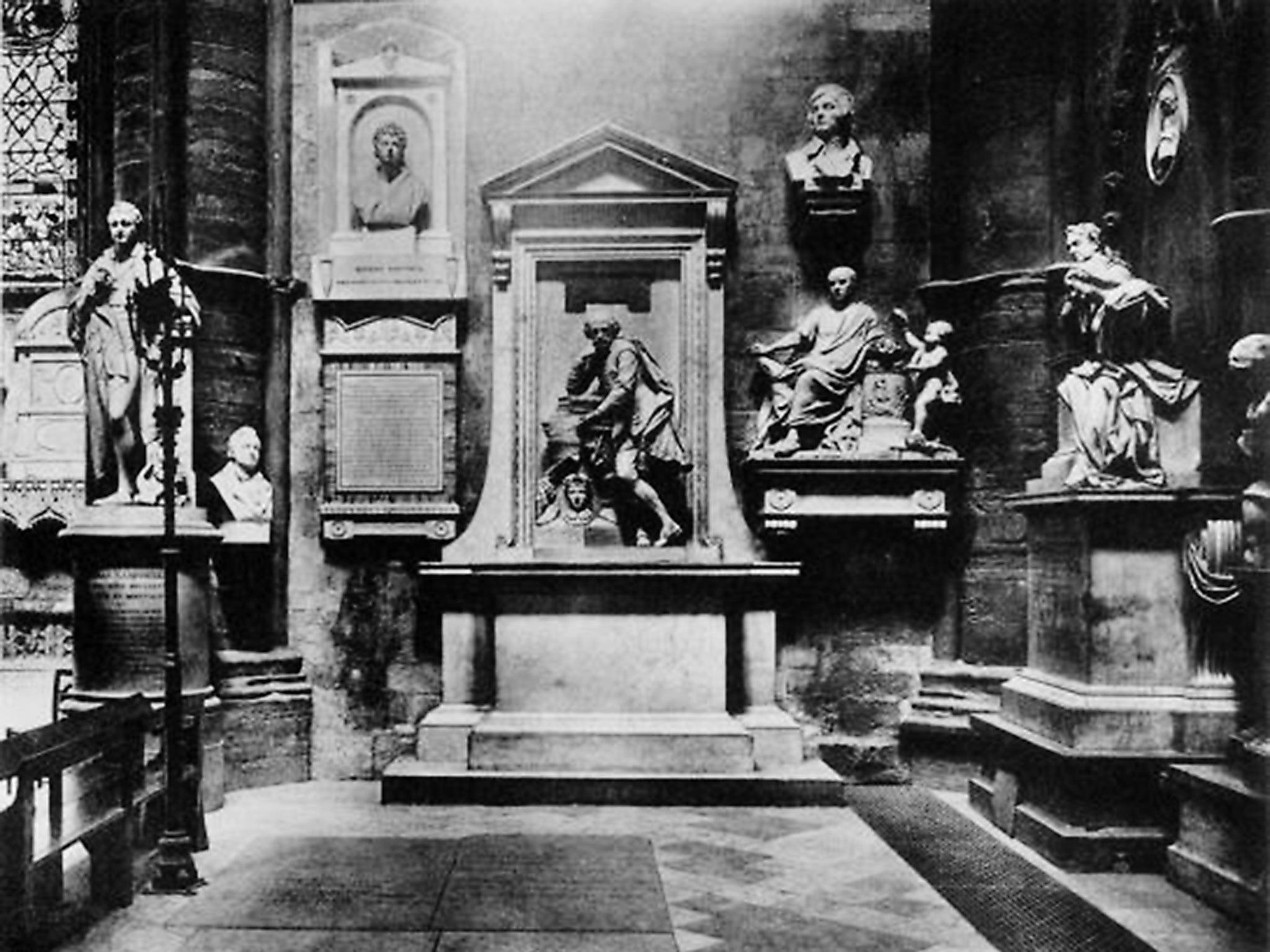

Poets’ Corner is one of the most famous areas of Westminster Abbey. The tradition of burying or commemorating the nation’s best writers there began in the 16th century, when a tomb was erected for Chaucer, buried in the abbey 250 years earlier.

English literary history is extraordinarily diverse, and scholars have subjected its canon – as both a concept and a holding place – to extensive critique since at least the 1980s. But as a reflection of literary history, Poets’ Corner is selective and partial, and it may be a long time before the south transept becomes less male and less white.

But then it was never 'designed', and chance has played its part in the erratic evolution of this collective memorial as much as cultural conservatism. Chaucer, for example, was buried there because of his day job as clerk of works to the Palace of Westminster; that he wrote The Canterbury Tales had nothing to do with it. And while 2016 has been a year of Shakespearean saturation marking 400 years since The Bard’s death, 124 years went by before the most famous name in English literature entered Poets’ Corner. Larkin’s 31 years isn’t much compared to that.

Larkin’s emotionally ambivalent attitude to Christianity is surely not unique these days. In Church Going, one of his most magnificent works, the narrator finds himself “at a loss”, unable to accept religious “superstition”, or even explain why he visits the church. But something pulls him there nonetheless – perhaps because “so many dead lie round”. Larkin keenly felt his own relation to the poetic dead; a stone bearing his name now lies close to at least two writers he worshipped, Thomas Hardy and D H Lawrence. There is much in Larkin’s work to suggest he would have been moved by this act of 'awkward reverence'.

James Underwood is a research fellow in modern and contemporary literature, University of Huddersfield. This article was originally published on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments