New edition of The Complete Plain Words will delight fans of no-frills prose - but can breaking the rules be the making of good writing?

The Complete Plain Words was first published sixty-five years ago and its impact on British society was immeasurable

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sixty-five years ago, Her Majesty's Stationery Office published its biggest-ever bestseller. It was nothing to do with income tax, local government or pet licences. It was The Complete Plain Words and, though its aims were modest, its impact on British society was immeasurable.

The author was a top civil servant called Sir Ernest Gowers, a former Private Secretary to Lloyd George who, in 1953, chaired the Royal Commission on Capital Punishment, which led to the abolition of the death penalty. During the Second World War, he was Senior Regional Commander for London – effectively in charge of the civil defence of the city during the Blitz and after.

One evening in 1943, to bolster the morale of exhausted civil defenders, Gowers was asked to give a cheery talk on some bureaucratic topic (you can imagine the excitement in the hall). He discussed the government circulars that his audience received every week: he poked fun at their grandiloquence and impenetrability, and called for a new, more user-friendly (though he probably didn't use that phrase) style of official communication.

Word filtered through to the Treasury about this radical initiative, and it asked Gowers to write a "training manual" for civil servants about using plain English. It was a hit. In 1948 Plain Words came out and sold 150,000 copies in eight months. The Complete Plain Words followed in 1954 and has never been out of print. To celebrate its 60th birthday, the author's great-granddaughter, Rebecca Gowers, has revised and updated the book for a new generation.

The revolution that lurked in its mild pages was not just a lexical but a social one. It was a radical reform of the language used by bureaucrats when communicating with the public. Official writing, says Gowers, "in the past… consisted mostly of departmental minutes and instructions, inter-departmental correspondence, and despatches to governors and ambassadors." Now, after the war, it was aimed at ordinary, mostly puzzled, British people, explaining their statutory rights and obligations and how they might be breaking the law. Gowers told his staff, in other words, how to talk to the post-war British population without sounding superior, baffling or plain rude. "Your style must not only be simple, but also friendly, sympathetic and natural," he said, "appropriate to one who is a servant not a master."

This was revolutionary talk in 1948. In the corridors of Whitehall, ministers questioned the impropriety of telling young civil servants it was OK to be "plain" in addressing superiors. But we can only cheer his advice to bureaucrats to stop sounding Victorian: to stop writing, "Your letter is acknowledged and the following would appear to be the position…" or "With reference to your claim, I have to advise you that, before the same is dealt with..." those chilly, robotic, passive constructions that drove a wedge between the man in the street and the chap in the ministry.

A tone Gowers is keen to eliminate can be heard in this letter to someone who lost their train ticket: "In the circumstances you have now explained, and the favourable enquiries made by me, I agree as a special case and without prejudice not to press for payment of the demand sent you, and you may consider the matter closed. I would however suggest in the future you should take greater care of your railway ticket to obviate any similar occurrence."

It's a tone of finger-wagging, fusspot, faux-officer-class authority ("You may consider the matter closed…") that Philip Larkin called "soppy-stern", that was embodied by Captain Mainwaring in Dad's Army, and that we now associate with the Harry Enfield character Mr Cholmondley-Warner. It was no small achievement that, after reading Gowers's book, people started writing "Thank you for your letter," rather than "Your communication of the 12th Inst. is acknowledged…"

Gowers's second ambition in the book was to rid English writing of "barnacular" style – a term deriving from the Tite Barnacle family, who run the Circumlocution Office in Dickens's Little Dorrit. It means writing that's stuffed with jargon words, worn-out phrases, tired clichés, the mistiness and imprecision of bureaucratic paragraphs that coil around the subject until it can no longer be glimpsed. Of course, writers have been complaining about vulgar new words for centuries – Jonathan Swift had a peculiar loathing for "mob," Doctor Johnson hated "fun" – and Gowers' strictures were part of a long tradition. This part of the book reminds us that, in trying to eliminate cliché and dullness, the mid-century writers set precedents – and several rules – that have survived, rather boringly, until today.

Gowers quotes earlier linguists as part of his clean-up campaign. In The King's English (1906), the Fowler brothers advised: "Anyone who wishes to become a good writer should endeavour, before he allows himself to be tempted by the more showy qualities, to be direct, simple, brief, vigorous and lucid." They recommended general rules:

"Prefer the familiar word to the far fetched. Prefer the concrete word to the abstract. Prefer the single word to the circumlocution. Prefer the short word to the long. Prefer the Saxon word to the Romance."

This always strikes me as perfectly sound advice to anyone trying to describe a wheelbarrow to a small child, or writing instructions for assembling a cupboard. It is, however, woefully constricting to anyone hoping to write with any trace of personality. Is the Saxon phrase "give up the throne" preferable to the music of "relinquish the throne"? Isn't the abstract (and Romance) word "sentiment" more expressive of emotion than the concrete (and Anglo-Saxon) word "feeling"?

Gowers clearly had doubts about the Fowlers' advice. He adapted it like this:

1. "Use no more words than are necessary to express your meaning, for if you use more you are likely to obscure it and tire your reader.

2. Use familiar words than the far fetched, if they express your meaning equally well; for the familiar are more likely to be readily understood.

3. Use words with a precise meaning, rather than those that are vague, for the precise will obviously serve better to make your meaning clear."

This seems like better counsel, but it gives rise to several questions. How do you work out how many words are "necessary" to express meaning? If Mike Tragic writes to beg Jill Flibbertigibbet for another chance at l'amour, his word-usage may stray well beyond what someone else might deem "necessary". As for "Use words with a precise meaning", shouldn't a linguist know that few words have monolithically "precise" meanings – in dictionaries they generally have two or more approximate definitions.

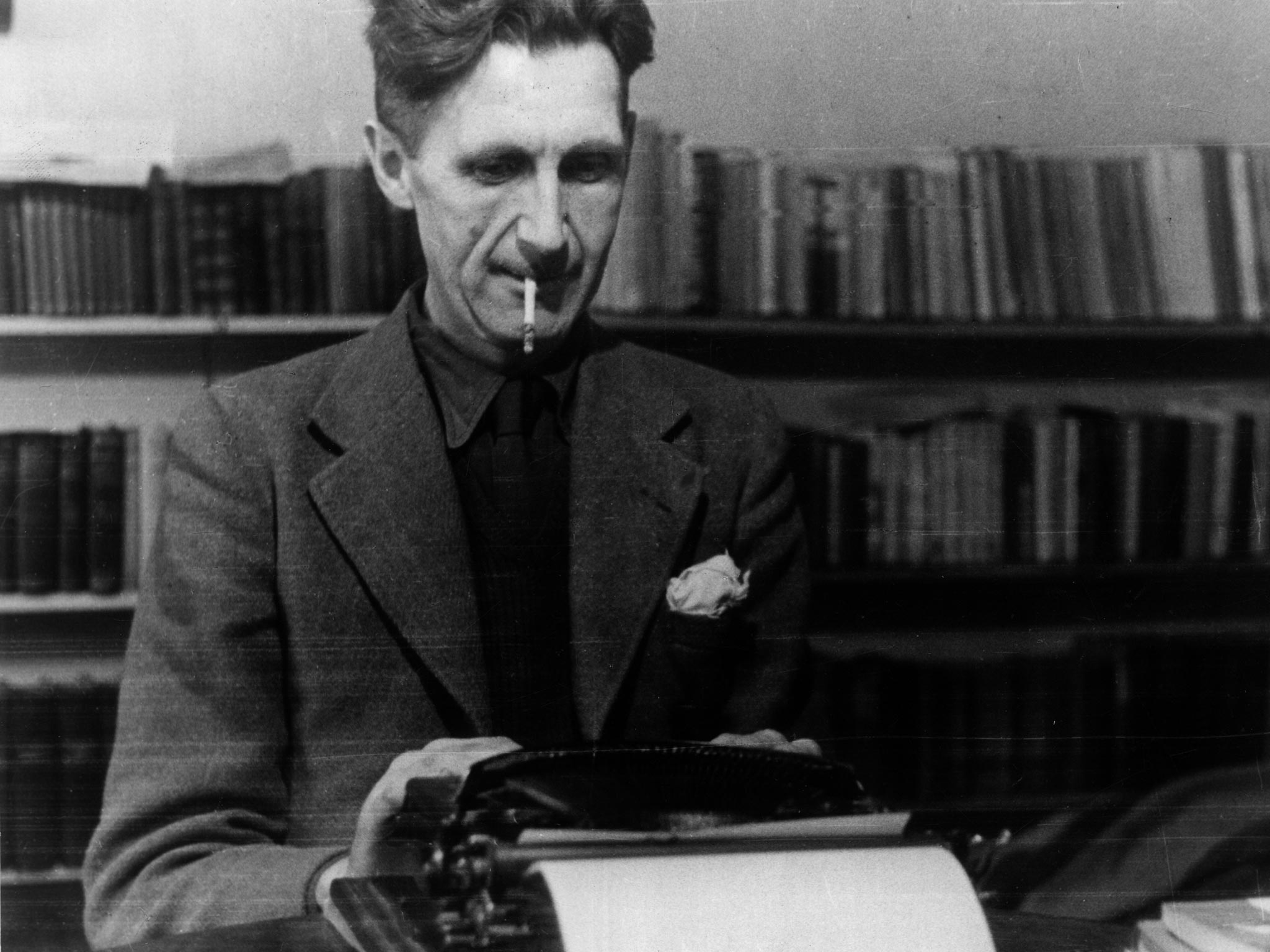

When Gowers launched Plain Words in 1948, he must have been aware of the looming shadow of George Orwell. Two years earlier, the author of Nineteen Eighty-Four had issued his own furious philippic against sloppy writing in his famous essay, Politics and the English Language. "[A] mixture of vagueness and sheer incompetence is the most marked characteristic of modern English prose, he wrote, "prose consists less and less of words chosen for the sake of their meaning, and more of phrases tacked together like the sections of a prefabricated hen-house." By the end of the essay, he was ready with six rules for good, or at least less-bad, writing:

1. Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

2. Never use a long word where a short one will do.

3. If it possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

4. Never use the passive where you can use the active.

5. Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

6. Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

You have to admire Orwell's self-detonating sign-off "(Break any of these rules…") but it's hard to admire the preceding commandments. "Never use a long word…"? So I mustn't say, "Lionel Messi's Terpsichorean grace", I can only say "Lionel Messi looked like a dancer"? How dull. "Never use a foreign phrase…"? Can I never again say "dans cette galere", or "avant la lettre" or "balcon formidable"? Must I say, "in this gang" and "before the word existed" and "big bust"? How boring, by comparison. Oh, and someone's found that 20 per cent of his sentences in the essay are passive.

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell used the idea of the "ready-made phrase" to invent the limited, emotionless, modular vocabulary of Newspeak (where "double-plus-un-good" means "really bad). His six rules of language have been taught for decades, as though warning young writers against using prose that showed off, tried new words and dance moves, acquired a foreign accent, pulled syntactical strokes, repeated itself, shouted, whispered, swore.

Well, when we've finished celebrating Ernest Gowers's socio-lexical achievement, and the curious convulsion that gripped him and Orwell, along with hundreds of thousands of British readers and would-be writers, in the 1940s and 1950s, we may feel that their keep-it-simple-keep-it-transparent strictures about prose have gone on long enough. I felt this some time ago.

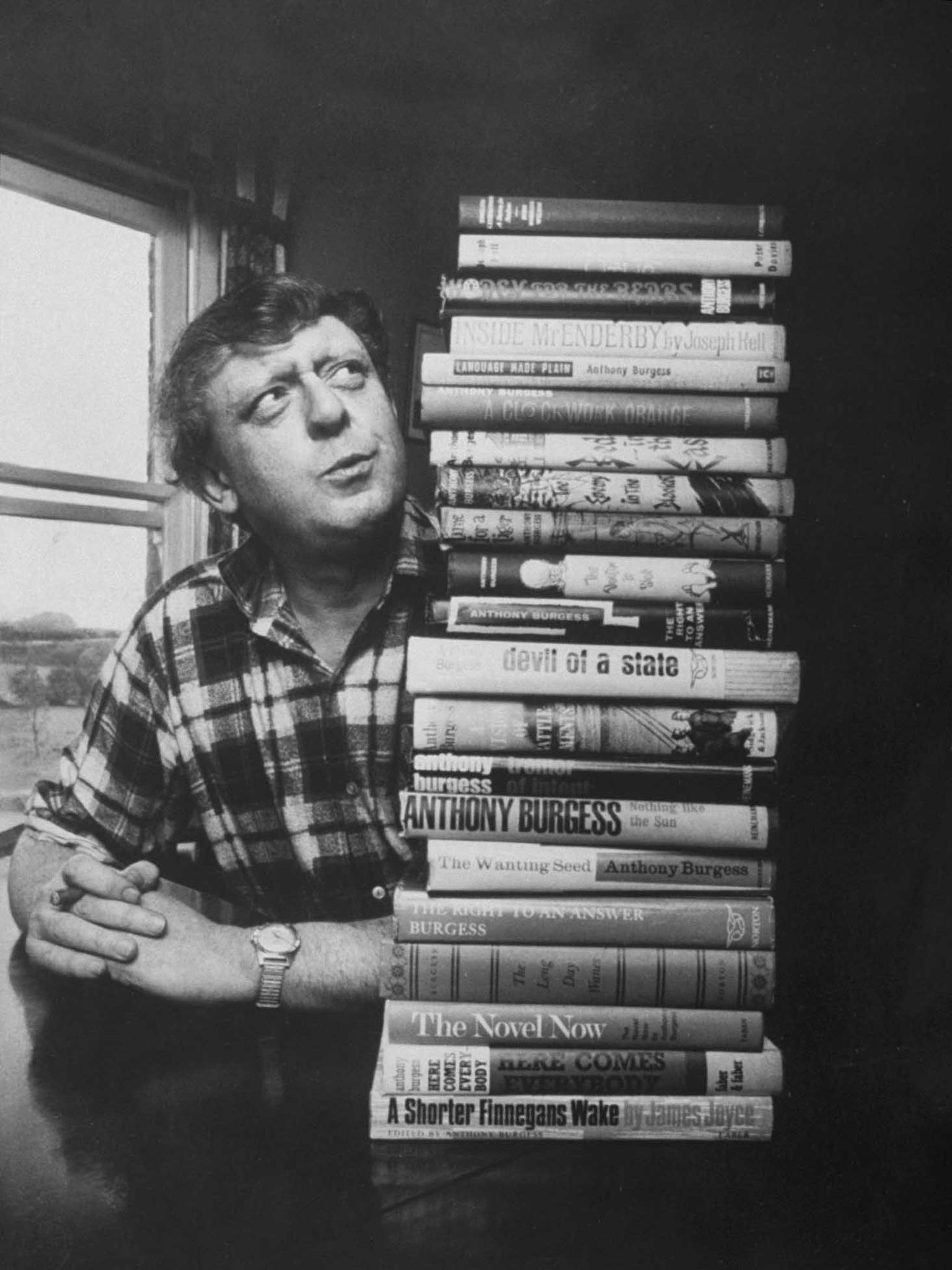

When I left university in 1975, writers such as Anthony Burgess were showing off all over the place. He loved what Hemingway called "those 10-dollar words", and threw them around profligately: "orchidaceous", "borborygmic", "steatopygous". He once wrote a sentence featuring the word "onions" three times consecutively, while still making syntactic sense.

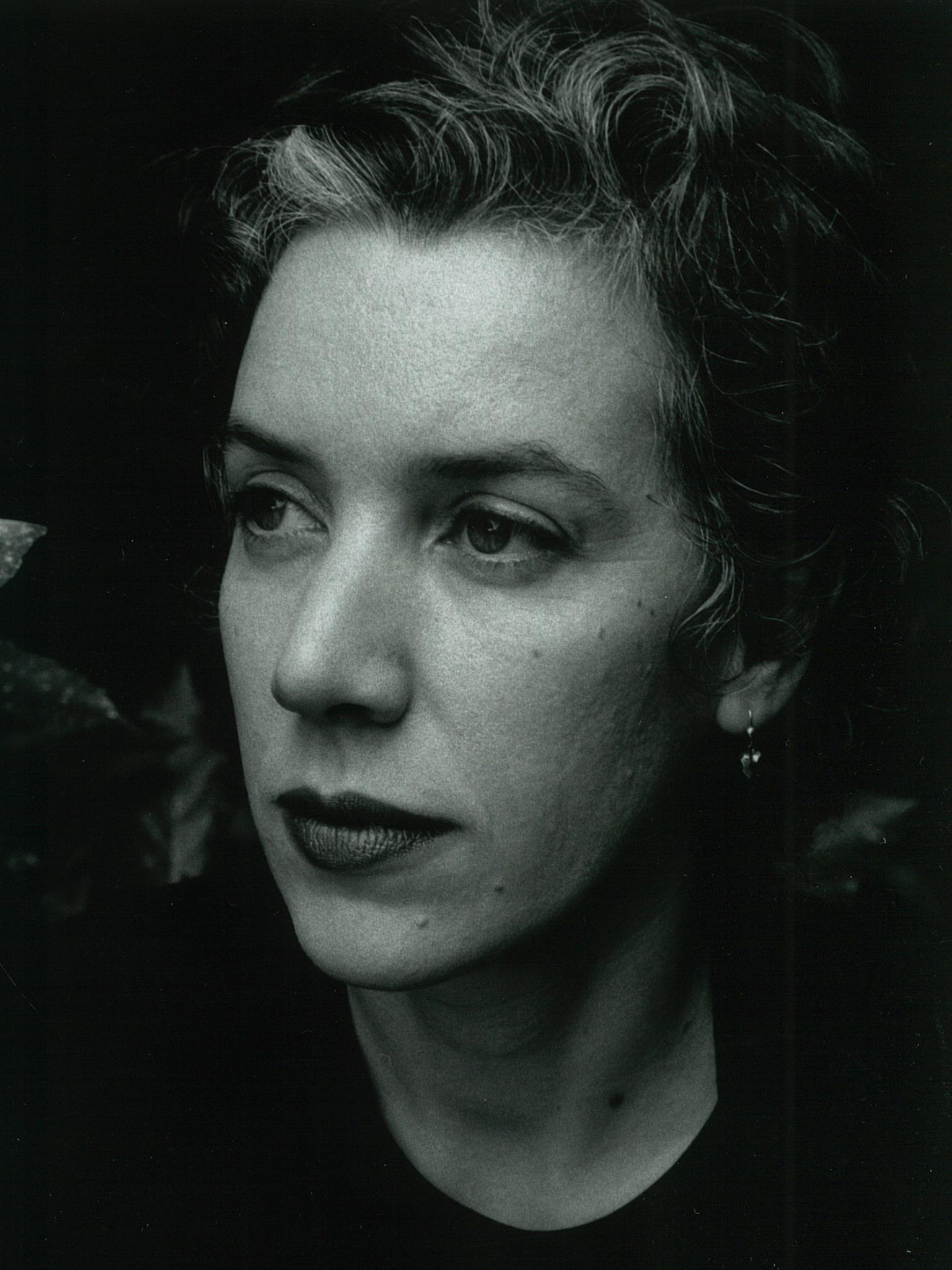

Angela Carter was writing thrillingly dense, darkly sexy novels about infernal desire machines, in which the prose showed not the slightest desire to be transparent. Soon after, Martin Amis joined the party and we all strove to emulate his cocky, elegant-sleazoid cadences. It was an exciting time.

I remember being shown the Gowers book and the Orwell essay, and wondering how anyone with ambition could still take them as some kind of Bible. I wish there had been a different set of precepts around, to which a tyro scribbler in search of a fancy prose style could have usefully turned. Maybe somebody should write them today.

'Plain Words', by Ernest Gowers and Rebecca Gowers (Particular Books, rrp £14.99), is out now. To buy it for £11.99 free P&P call 08430 600030 or visit independentbooksdirect.co.uk

Take risks, include sex: An alternative guide

1. Don't be content with the ordinary. Remember what Updike said about Nabokov: "He writes prose the only way it should be written – that is, ecstatically."

2. In Lolita, Nabokov described the Rockies as "Heart and sky-piercing snow-veined colossi of stone." Could you write something similar about Clapham Junction underpass? (Of course you could.)

3. Don't be afraid of using repetition to paint a picture. Look at the litany of falling snow at the end of Joyce's 'The Dead', an effect later pinched by everyone from Alan Paton to Bret Easton Ellis.

4. If you discover a picturesque Victorian phrase languishing unused – tatterdemalion, slubberdegullion, Dundreary – store it in your mental cabinet of curiosities and bring it out later. It hasn't done Will Self any harm.

5. If you're afraid that an extended, unparagraphed tirade of reflection is becoming wearisome, re-write it to incorporate the preparing of a fancy meal. You'll be saved by parsnips and rocket.

6. Pay no regard to the Bad Sex Award. Go ahead and describe sex as much and as precisely and flamboyantly as you like, remembering to steer clear of metaphors involving beaches or the North Pole.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments