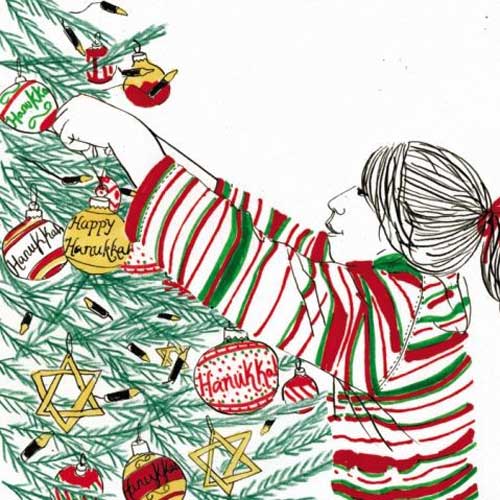

Neil Gaiman: Hanukkah with bells on

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I do not recall lobbying for anything, as a boy, as hard as I lobbied, with my sisters, for a Christmas tree.

My parents objected. "We're Jewish," they said. "We don't do Christmas. We do Hanukkah instead."

This did nothing to stop the lobbying. Anyway, Hanukkah was no substitute for Christmas. My parents, unlike my grandparents, didn't always remember to keep Hanukkah, and even when my mother remembered the festival, we children could see that a menorah and candles were not a Christmas tree. My parents kept kosher, went to shul on high holy days but that was the extent of things in our house. My grandparents were properly observant Jews. My parents were not particularly observant Jews, while we children were, quite simply, bad Jews. We knew we were bad Jews because we wanted a Christmas tree.

We were surrounded by Christmas, after all. When I was eight I was offered the choice of playing a shepherd or wise man in my school Nativity play. I was a precocious child and I had read widely, so I argued with the primary school teacher, pointing out that you could choose either to have wise men or shepherds, but not both, as the gospels of Luke and Matthew contained accounts of very different nativities. Wisely, she declined to argue theology with an eight-year-old, and instead pointed out to me that, as first shepherd, I would also be the narrator and would read from a scroll, and, fearful of losing what was going to turn out to be a fairly good part with no actual lines to learn, I stilled my tongue.

Christmas presents, that was a battle we had already won, my sisters and me. It didn't matter that my mother wrote "Happy Hanukkah" in my Doctor Who annual with William Hartnell or Patrick Troughton on the cover: the book still arrived on Christmas day, in a pillowcase filled with gifts. What the present was called was mere semantics: as long as we got the swag we did not care what was written on it.

We were not jealous of friends who got Christmas presents. We were jealous of the friends with Christmas trees. Having a Christmas tree was what Christmas was all about. It had nothing to do with mangers and shepherds and (more properly, as I would no doubt have told you at length back then, or) Wise Men. Not as far as we were concerned. It was trees all the way, properly decorated ones, with tinsel and glass balls and a star on the top. We lobbied and we lobbied hard, and we would not give up. My parents would not countenance it. They had not had Christmas trees when they were children; instead, they had parents who disapproved of Christmas trees. You couldn't, my mother told us, be Jewish and have a Christmas tree.

I was a precocious child, and I had read widely, and I struck. "But it's not Christian," I said.

"I think you'll find it is, dear," said my mother. "That's why they call them Christmas trees, after all."

"They are actually," I told her, proudly, and precociously, "a pagan relic. The trees. The thing of people bringing trees into houses at the winter solstice and decorating them has nothing at all to do with Christianity. It's from pagan times."

I'm not sure why it was better to be a pagan relic, but I hoped it was, and it seemed to shake my mother's certainty. Like my teacher, she knew better than to argue theology with an eight-year-old.

Whether it was, as I thought at the time, my precocious argument or (more probably in retrospect), my sisters' huge, pleading eyes and trembling lower lips, I do not know, but my father went to the local market and picked out a Christmas tree for us and brought it home. We decorated 'it, and were content. Having won the Christmas tree battle, we had, somehow, won the Christmas war. My father even dressed up, that Christmas Eve, as Father Christmas, with an enormous cotton-wool beard, to place our presents by our beds.

We pretended to be as asleep as we could.

"What was that about?" I asked my sister, after he had gone.

"It was just Dad," she whispered.

"Are you sure?"

"He was wearing Dad's dressing-gown," she said, sensibly. "Of course it was him."

It seemed to be one the best things about having a good Jewish Christmas: we were never obliged to believe in Father Christmas, and the experiment was never repeated. But the Christmas trees were there to stay. A Christmas tree was bought, normally on the last Saturday before Christmas, for the rest of my childhood.

Our more orthodox cousins, profoundly treeless, were both scandalised and impressed by this. But we were happy. We had a nice Jewish Christmas. We were content.

Neil Gaiman's new novel, 'The Graveyard Book', is published by Bloomsbury

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments