Michael Pollan: ‘Capitalism is falling in love with psychedelics. There’s a gold rush’

The food writer has become a psychedelic convert in his mid-sixties. He tells Kevin E G Perry how caffeine fuelled modern civilisation, why the war on drugs has failed, and the benefits of ‘ego death’

While writing and researching his two most recent books, How to Change Your Mind and This Is Your Mind on Plants, the author Michael Pollan dosed himself with all manner of psychoactive substances, ranging from LSD and mescaline to the venom of the Sonoran Desert toad. The morning we speak he’s at it again. When I ask over a video call to his window-lined home office in Berkeley, California whether he’s yet had his daily fix, he raises a cardboard coffee cup to his screen in salute before taking a long pull. “I’m in the middle of it!” he says with a nod.

The 66-year-old American quit caffeine for three months as an experiment while working on This Is Your Mind on Plants, but says he’s now happily returned to his old habit. The fact that caffeine, the world’s most popular psychoactive drug, is rarely grouped with the various illegal substances he writes about is, he argues, part of the problem. As a society we have elevated certain drugs to the status of cornerstones of our civilisation while irrationally outlawing a whole swathe of potentially beneficial chemicals.

Pollan argues the challenge facing us is how to reintegrate these substances into society. “One of the casualties of the drug war is lumping them all together,” he explains. “They’re more different than alike. You’ve got stimulants and depressants and psychedelics and one size isn’t going to fit all when it comes to figuring out how to weave them into our culture.”

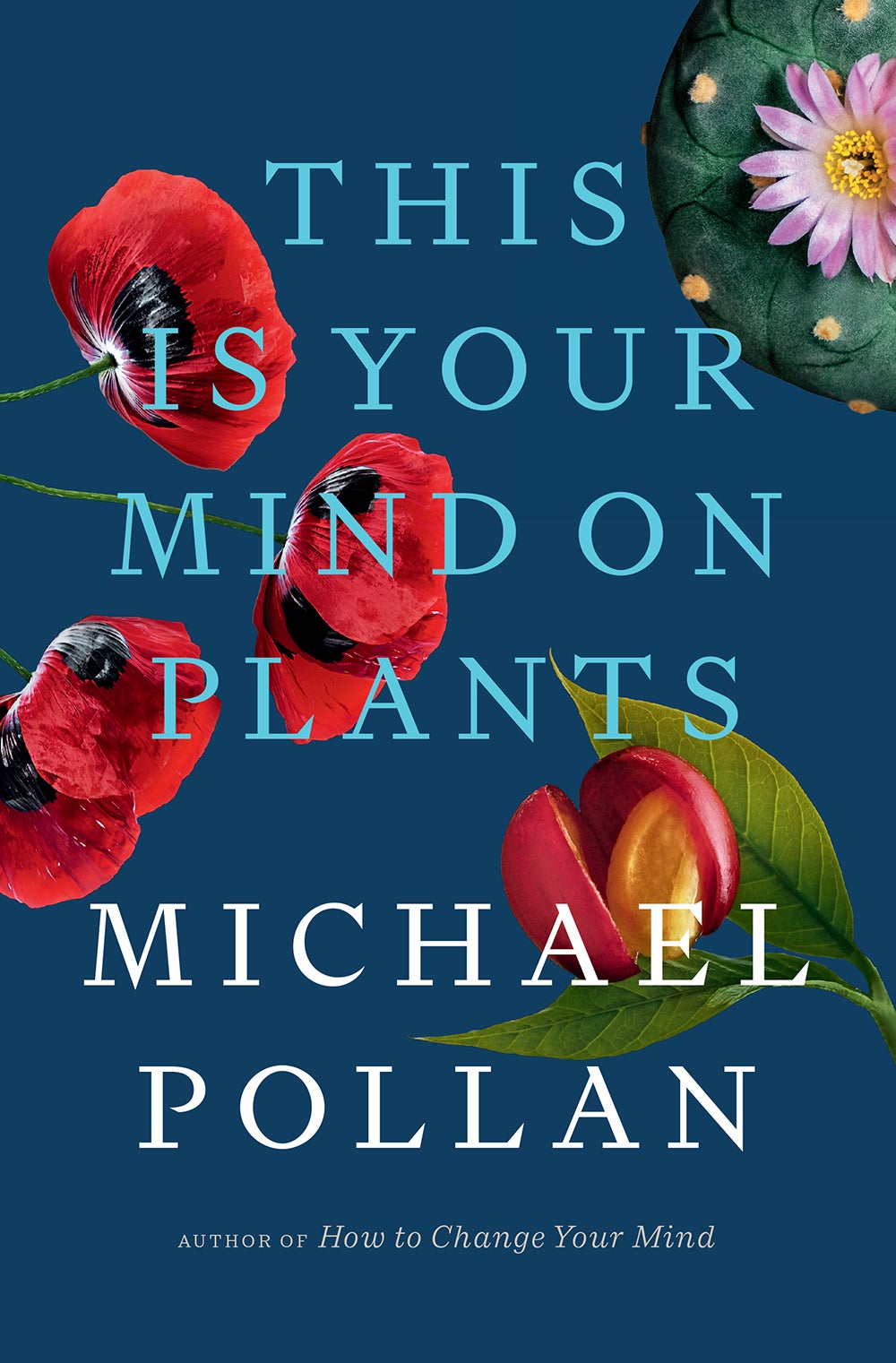

In This Is Your Mind on Plants, Pollan profiles one each of the categories he’s just outlined: a stimulant, caffeine; a depressant, opium; and a psychedelic, mescaline, which occurs naturally in both the peyote cactus and the San Pedro cactus. Of the three, caffeine is clearly the one that’s best integrated into the modern world. Indeed, Pollan convincingly makes the case that to a large extent caffeine helped build it. Prior to the arrival of coffee and tea in Europe in the 1600s, he writes, the English would typically drink alcohol morning, noon and night. The introduction of caffeine had an enormous impact, both pharmacologically and socially. Pollan quotes the historian James Howell, who observed as early as 1660 that “this Coffee drink hath caused a greater Sobriety among the Nations”.

“We know that a lot of Enlightenment figures, like [18th-century French philosophers] Diderot and Voltaire, were major caffeine addicts,” points out Pollan. “Caffeine is very mixed up in the rise of rationalism and the Enlightenment, and then I think the Industrial Revolution. It’s hard to imagine people getting comfortable operating heavy machinery, working night shifts or doing double-entry bookkeeping without this kind of linear, focused consciousness.”

Caffeine, it turned out, was the perfect drug to fuel capitalism. Reading This Is Your Mind on Plants, I felt the scales fall from my eyes as I realised why almost every workplace I’ve ever been in has offered free tea and coffee to its employees. “The coffee break tells you all you need to know about the links between capitalism and caffeine,” nods Pollan. “The idea that your employer would give you a free drug, and then paid time in which to enjoy it, tells you everything. Who wins here?”

Pollan draws a distinction between caffeine’s obvious benefits to the grand project of civilisation and the thornier question about whether all of this caffeinated progress was good for humanity as a species. “It depends on how you feel about civilisation, which has given us many, many blessings, but there’s been a trade-off,” he argues. “The trade-off has been a kind of violation of our species-life as animals. Living by the rhythms of the sun makes a certain sense and still sits well with our biology, but the whole course of history has been to take nature and civilise it in various ways, including ourselves. We domesticated ourselves, as well as all these other species.”

For an example of how not to integrate a drug into society, one only has to consider the opium poppy. In 1997, Pollan published an essay in Harper’s Magazine that recounted his experience growing poppies in his own back garden. It is reproduced in This Is Your Mind on Plants, complete for the first time with details about how he used them to make opium tea and a “trip report” about his experience drinking it. These sections were both removed from the original piece under the strenuous advice of his lawyers. At the time, America’s Drug Enforcement Administration were cracking down on the (legal) sale of poppy seeds and even pulling up the poppies which grew freely on the grounds of Thomas Jefferson’s home at Monticello. Meanwhile at the very same time, Purdue Pharma, owned by members of the Sackler family, were beginning to market a new, slow-release opiate called OxyContin.

“Supposedly it was less dangerous, less addictive and less subject to abuse,” says Pollan. “Boy, did they get that wrong!” In 1997, there were thought to be around half a million heroin addicts in the United States, and about 4,700 overdose deaths each year. Now, an estimated two million Americans are addicted to various opiates and there are about 50,000 overdose deaths each year. Four out of five new heroin users used prescription painkillers first. “I think this is one of the things that has taken the wind out of the sails of the drug war in the US,” says Pollan. “It’s very hard to justify when the biggest problem, the problem that led to 800,000 overdose deaths and an explosion in the number of opiate addicts, was the result of legal psychoactive drugs, not illegal ones.”

From Pollan’s vantage point in California, it appears the war on drugs is petering out. He is aware though that the view from the UK is very different. In California, medical cannabis has now been available for 25 years. In the UK, despite the drug ostensibly being legalised for medical use in 2018, only three patients have yet been able to secure prescriptions on the NHS. “I’m hoping as the United States ends the drug war [it will have a knock-on effect] in the same way that NATO allies left Afghanistan,” says Pollan with a smile. “I’m serious in the sense that the US has been a powerful force in enforcing these international drug treaties, which we really pushed the rest of the world to sign on to. I think as we get off that train it’ll be easier for other countries to do so, but I do know that in the UK you’re not nearly as far along in this process and the drug war still rages there.”

One of the more significant recent victories in the fight to end the drug war came last November when Oregon voted to legalise psychedelic therapy and decriminalise the possession of all drugs. Washington DC has also recently decriminalised psychedelic plants. Pollan’s 2018 bestseller How to Change Your Mind, a personal but clear-eyed account of the science of psychedelics and their enormous potential to help people suffering from depression, addiction and anxiety, has been credited with helping to sway public opinion.

In that book, Pollan recounted his own experiences using psychedelics, including a trip during which he experienced “ego death”, an experience in which psychedelics cause a complete loss of any sense of self. “It wasn’t frightening,” says Pollan. “It seemed like the most natural thing in the world. I continued to perceive without my ego, which gave me some perspective on my ego. It’s not the be all and end all.”

For Pollan, who made his name as a food and nature writer before his love of plants led him to become curious about their psychoactive qualities, the most significant realisation that came from taking psychedelics was that it is perfectly possible to have a profound spiritual experience without any sort of religious or supernatural belief. “For me there was a re-understanding of what the word ‘spiritual’ means,” he says. “‘Spiritual’ is really about a deep connection, a connection to other people, a connection to nature, a connection to the universe, and that is not imagined. We are more connected than we think. Our baseline consciousness is designed by evolution not to perceive the world accurately, but to get s*** done. It’s very good for that, but there is more truth than we perceive. Psychedelics give us a window. The experiences that I’ve had on psychedelics, strange as they were, are closer to the truth of the matter than the insights of everyday normal consciousness.”

One of the few psychedelic substances that Pollan didn’t try in the process of writing How to Change Your Mind was mescaline. In This Is Your Mind on Plants, he writes about how his original plan to join a Native American peyote ritual was scuppered by the Covid pandemic. While he eventually had a powerful mescaline experience at his own home, and cultivated the San Pedro cactus in his garden, through his research and interviews he came to understand the significance of having a group setting in which to use psychedelics productively. “I think we have a lot to learn from indigenous use of psychedelics,” he says. “They’ve been at it a lot longer than we have. These substances didn’t show up in the West until the mid-20th century, but they’ve been used for thousands of years in other cultures.”

He believes these lessons will be valuable as society seeks to find a way to make use of psychedelics that doesn’t either over-medicalise them or abandon them to the whims of capitalism. “Capitalism is falling in love with psychedelics right now,” he points out. “There’s this gold rush of investment, hundreds of millions of dollars in just the last year. Whether it’s going to work is another question. I think it’s going be very challenging to fit into the system.”

He can see a world not too far off where psychedelic retreat centres, complete with medical assessments and “trip guides”, could become commonplace. He also believes we may see the founding of new religions. “There are already three [which use psychedelics], the Native American Church and two ayahuasca religions,” he points out. “I think the Supreme Court is going to be hard-pressed to say that the Church of Lysergic Acid is not a church, so that’s going to be interesting to watch.”

In the end, he says, the most important thing to remember about all drugs is that they offer both opportunities and risks. “The Greeks had it right when they used this word ‘pharmakon’ for drugs,” he says. “It meant blessing and curse at the same time. We need the negative capability to hold these two ideas in our heads at the same time and deal with the ambiguities. The attempt to simplify our understanding and approach to drugs gave us the drug war. We could simplify in the other direction and say anything goes, and I think that would have problems too.”

What we really need, he argues, is new kinds of social norms that can guide the use of drugs without falling back on prohibitionist moralising. “I’m a great believer in these cultural containers,” he says. “We have one for alcohol. It’s not perfect, but we have all these kind of informal rules that people don’t drink till the evening, or they drink with other people, or with food. These rituals are very protective. We have to figure out the right rituals for each drug.”

‘This Is Your Mind on Plants’ by Michael Pollan is out now.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks