Ma Jian: Slaughter and forgetting

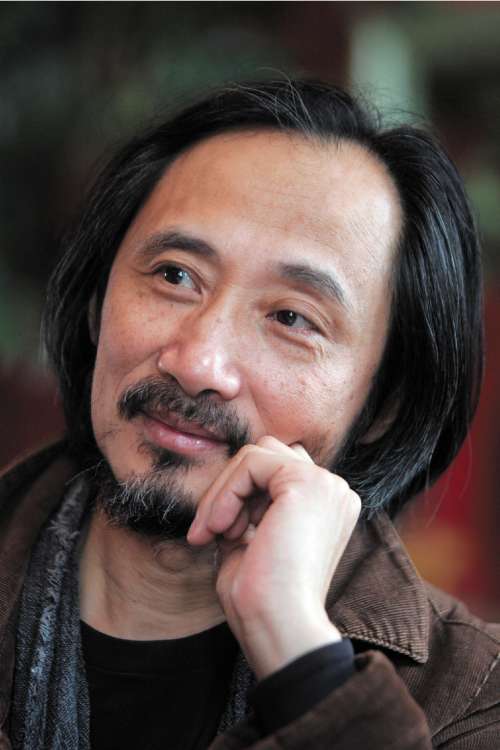

Ma Jian's epic of the Tiananmen massacre and its aftermath will make waves across the world. Boyd Tonkin meets the exile who dares to remember China's past

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.During the Tiananmen Square massacre of June 1989, Chinese security forces killed many of the students and supporters who had over six weeks demonstrated for democratic reform. Estimates of the dead range from just under 1,000 to over 7,000. Last year, prior to the anniversary, a small ad surfaced in a Beijing paper. It read: "Respects to the mothers of 4 June". The young clerk who took the words down had no idea of their significance, though ignorance did not save her from the sack when this sole allusion to the protests saw print. "The tragedy is that this girl didn't even know the importance of the date," says the exiled Chinese author Ma Jian. "This whole period in Chinese history has been completely erased." He adds that, "I wanted to chronicle these events, to hammer them down like nails in a piece of wood, so no one would be able to forget."

His new novel, Beijing Coma (translated by Flora Drew; Chatto & Windus, £17.99), does much more than that. Its appearance, just as the giant propaganda juggernaut built in preparation for the Olympic Games looks liable to topple over in the face of global anger over Beijing's record of repression, is an event that should, and will, resonate around the world. It establishes Ma Jian, already the author of three free-spirited books about the post-Mao country which he finally left in 1997, as the Solzhenitsyn of China's amnesiac surge towards superpower status. "When history is erased, people's moral values are also erased," he says. "It was from a sense of rage at this whitewashing of history that I felt the need to bear witness." In dictatorships, there must be "a constant struggle between the authorities who want to control history and the writers who want to grab hold of it and reclaim it."

Like his Soviet counterpart in the glory days of dissent, but far gentler in manner, Ma combines a gift for densely detailed, panoramic fiction with a resonant prophetic voice. The mass state murders of 1989 damaged us all, east and west, he maintains. Protesters were "mown down by the tanks of a regime that survived this blip and went on to become the world's best friend." Effectively, the Communist Party got away with it as China's great leap into prosperity began. This impunity "has had a damaging effect on the world's civilisation." Now, foreign leaders may know that Hu Jintao, China's president, "is a liar. But they still agree to be friends. This act of stretching out your hand to these people corrupts the world's moral values."

Beijing Coma not only commemorates an epic rebellion but helps to renew it; this time, in context. It paints the big picture of past, present and future that eluded the rebels, whose tragedy was that "when they entered history at that moment, they had no sense of history. They got swept up in this movement that had a momentum of its own... They blinded themselves to the historical fact that the old guard will destroy the new guard in the end."

Great events, as the novel indicates, can grow from a multitude of tiny acts in mundane places. Aptly enough, we talk about this epoch-making cry for freedom in a west-London café where the worst we have to fear is a concerted advance by yummy mummies armed with heavy-duty strollers. Still jet-lagged, Ma has just returned from a trip to China, where he studied with dismay the wave of pre-Olympic mania and "anti-Western rage": "Beijing has become a theatre, and it's as if everyone is acting out this absurd play. It reminded me very much of the atmosphere of the Cultural Revolution, when the government whipped up the people into a nationalistic frenzy." He may visit as a private person, but can never speak, read or attend public meetings as an author: "They let you know that they are watching you all the time, and that in itself instils fear." Beijing Coma is due to appear in a Chinese edition in Hong Kong and Taiwan; piracy and smuggling will then take it to the mainland. He will be read, and heeded.

Originally a painter and photojournalist, Ma Jian left his job in 1983 after a crackdown on "spiritual pollution" - ie, bohemian types like him. He set out on the eye-opening journey through unofficial China that became his travel book, Red Dust. A separate set of gritty tales from Tibet, Stick Out Your Tongue, led to his banning as he moved to Hong Kong. He quit the colony for Europe when it reverted to Beijing's control. After a spell in Germany, he relocated to London, where he lives with his translator Flora Drew, his partner in life as well as literature. With formidable fluency and velocity, she converts his low and liquid flow of Mandarin into idiomatic English. But what, I want to ask her, is Ma's Chinese prose like to read, and to translate? "It's so crystal-clear, so direct. He's not hiding anything. It has this breath of life; this naturalness... a liberating quality, but also this great poetic depth."

Beijing Coma may have huge documentary value, but it grips and moves as epic fiction above all: "First and foremost, this is a novel. I believe that the power of literature is stronger than the power of tyranny." Its hero Dai Wei, a postgraduate biologist from a musical family purged, and broken, in Mao's Cultural Revolution, is felled by a stray bullet as tanks and troops smash the protests in which he served as a security chief. Through the 1990s he lies in a coma, silently observing China's stampede towards consumer heaven (and hell). Flashbacks depict the drama and terror of events around the square. With its incremental, slow-build crescendo, the novel asks for the reader's patience, but rewards it in scene after scene of black satire, lyric tenderness and desolating tragedy.

From Dai Wei's bed-bound "hibernation" to the students' fateful drift from drinking, flirting and love-making to the bloodbath that awaits them, Beijing Coma has the visceral physicality that stamps all of Ma Jian's work. He is a poet of the body in all its ecstasies, embarassments and agonies. "We live in our bodies but these bodies are doomed to become dust," he explains. "The Chinese title for this book would be 'From Flesh to Dust'." Equally, "Tyrannies not only want to control your mind and thoughts but your flesh as well. Under tyrannies, you're not even master of your own body." Journalists write glibly of the beings that once ate hungrily, got tipsy, felt pleasure, being "crushed". Ma, the true materialist, shows just what that means. "In a tyranny, in the end what will be destroyed is your flesh, if you oppose the state." So physical emancipation must underlie political revolt: "Only when you are aware of the uniqueness of everyone's individual body will you begin to have a sense of your own self-worth."

For all its cathartic fury and compassion, Beijing Coma shows that "really, there are only two options open to people: either to be a slave, or to be an outcast. It's about what you have to lose in order to survive." At the close, as the apartment where Dai Wei has watched and remembered falls to a developer's bulldozer, China's newly-bloated body politic seems to have forgotten freedom's taste. For Ma, the sheer opportunism of today's elite has reinforced its hold. "Ideologically, it's a vacuum. No one within the leadership actually has any belief in Communist principles themselves. They are there for reasons of personal gain." The Party "has become a very pragmatic system... It isn't constrained by any beliefs because it has none."

On the boycott question, he believes that all politicians should stay away from the Games but that athletes should go: they "will have the positive effect of drawing world attention to human-rights abuses". Meanwhile, the militant chauvinism uncorked by Beijing could backfire: "Despite its apparent might, one shouldn't assume that this Party is indestructible. Once you stir up this nationalist fervour, no one can predict where it will turn. Perhaps it could end up destroying the Party itself."

As the book thunders towards its finale, a sparrow visits comatose Dai Wei. Does it have a special status in Chinese poetic tradition? Quite the opposite: "It's the most humble, worthless bird. Mao launched these campaigns encouraging people to eliminate all the sparrows. I wanted to use this most insignificant, most derided creature, and to make it a symbol of this quest for freedom." Eventually, the frail bird will become "a featherless, immobile little creature with broken wings, powerless to fly away". But the novel that hosts this sparrow is destined to be an eagle whose wings will cross the world. In Beijing, powerful heads will hear them beat, and worry.

Biography

Ma Jian

Ma Jian was born in Qingdao in 1953. After political pressure, he quit his job as a photojournalist in 1983, travelled throughout China and later turned these experiences into Red Dust. His fiction about Tibet, Stick Out Your Tongue, was banned at the time he moved to Hong Kong in 1987. He continued to travel in China, and took part in the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989. In 1991, he published The Noodle Maker. He left to live in Europe in 1997. Beijing Coma, his novel of the Tiananmen massacre, is published by Chatto & Windus. Ma Jian lives with his translator, Flora Drew, in west London; they have two small children.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments