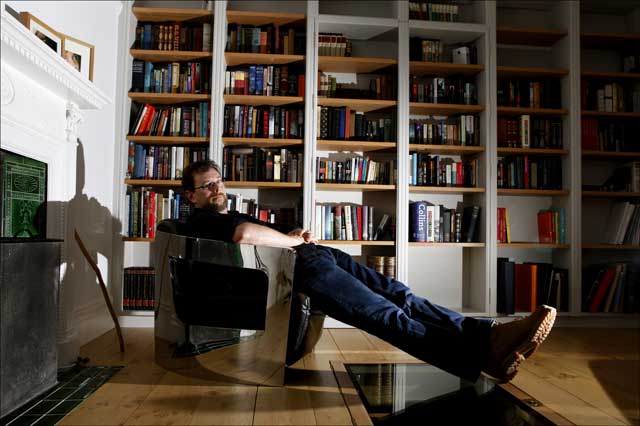

Lie back and think of Genghis: Conn Iggulden reveals the inspirations behind his historical fiction

The best thing about writing historical fiction is that the story has already been told. All Conn Iggulden – the bestselling author of 'The Dangerous Book for Boys' – has to do is imagine the gory details...

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.By anybody's standards, Conn Iggulden is a staggeringly prolific author. Since his The Gates of Rome appeared in 2003, he has produced a 400-page-plus historical novel every year – that's four of his "Emperor" books (about Julius Caesar) and three in his "Conqueror" series about Genghis Khan – totalling three million in sales. The fourth instalment of the latter series, Empire of Silver, is out this month. Plus, there has been a children's book about tough faeries, Tollins; a novella, Blackwater, for 2006 World Book Day; and the title with which his name is most readily associated, The Dangerous Book for Boys, co-authored with his younger brother Hal, which has sold four million copies and spawned a whole industry of spin-offs. In 2007, he was the first author ever simultaneously to top the UK's fiction and non-fiction bestsellers' charts.

Yet, when I remark on his prodigious rate of output, Iggulden looks sceptical. "I always think I could be more productive," he confesses. "There are some writers who do an awful lot more. Bernard Cornwall [one of his heroes] does two books a year. And then there's the one who really bugs me, James Patterson, who manages 14 new releases – seven hardbacks and seven paperbacks – a year."

This sort of "must-do-better" self-deprecation can often be an invitation to offer more plaudits, but Iggulden gives every appearance of being a genuinely modest man. (His website, while promising he will read every forum post, also cautions "no foul language you wouldn't think you could say to your grandmother".) All of which means that my couple of hours spent with him at the kitchen table of his big Edwardian family house in Hertfordshire quickly becomes a playful tussle to get him to take himself and his success seriously.

Given the tone of The Dangerous Book for Boys – all health-and-safety-defying jolly japes with ropes, ponds and chemistry sets – I had fondly imagined Iggulden would be the sort to do his writing in the garden shed, accessible only by a zip-wire. "No," he says apologetically. "I have a room upstairs." There he turns out a steady 1,000 words a day. Doesn't he ever get writer's block? "Well, I do and I don't. It's probably embarrassing to say but because it is historical fiction, I always have the story laid out before me. So just by reading around the subject, I come across quite a lot of details that I instantly know will make a good scene."

There again is that tendency to downplay his achievements – and his sheer stamina (he is a 38-year-old father of four children under nine, plus two dogs, one deaf and one frightened of everything and anything). Writers of historical fiction, in my admittedly limited experience, are usually all too keen to stress how much research they do, and how the novelist's imagination is just the icing on the cake of what is, at heart, a serious, meticulous, quasi-academic line of work. Iggulden, by contrast, appears anxious only to make it all sound: a) fun, and b) none too onerous. "My mother was a history teacher," he offers by way of explanation of his methods, "and she brought me up with the idea that we haven't evolved. So historical characters are still basically the same people we are; they just lived 1,000 years ago."

He has moved to the open back door to sneak a Silk Cut by the time we get on to his long incubation as a published author. There is a pile of manuscripts in his attic that he sent to commissioning editors at the rate of one a year from the age of 13 until, finally, someone bit as his 30th birthday loomed. "They are all neatly wrapped in brown paper and string," he adds, "which is why we included how to make brown-paper parcels in The Dangerous Book for Boys. I'd had plenty of practice."

Once seated back at the table – or rather, restlessly moving about at the end of it – he relives the long years of rejection slips and how he very nearly gave it all up as a bad job. "When I was teaching [before his breakthrough, he spent seven years at a Catholic comprehensive teaching English and drama], I was writing only the beginnings of novels and sending them off. I could do them very quickly, though perhaps, on reflection, speed wasn't the most important thing. I'd tried writing just about anything you can imagine except for romance. Twice, publishers came back to me to say, 'We like your beginning, can we see the rest?' There were so many beginnings, I was never sure which one they were talking about. And then I got all buoyed up on the excitement of their interest, finished the manuscript, and they still said no, which was absolutely soul-destroying."

It is clear from his face – usually animated in a slightly overgrown-schoolboyish way, but while he says these words suddenly melancholy – that the memory of those rejections remains close to the surface. Though he had long been a reader of historical fiction – Patrick O'Brian was a teenage staple – it had never occurred to him that he could write it. But then something about the story of Julius Caesar caught his imagination. Iggulden told his wife he was giving it one last try before "I'd settle down to a lifetime of teaching". Would that have represented failure? "Not at all. I still have a teacher's tweed jacket on my soul."

He'd chosen a tough road. As one of his editors told him, in the late 1990s, "You couldn't give historical fiction away. The only person active back then was Bernard Cornwell." But, in 2000, along came the globally successful film Gladiator. "I sometimes wonder," Iggulden reflects, "how much of my career I owe to Gladiator. It sparked an interest in Ancient Rome. There have certainly been an awful lot of books about Rome since. And now they've moved on to the Vikings. There are patterns. People look for gaps."

Such as Genghis Khan? The 13th-century Mongol emperor hasn't traditionally held much appeal save for brutes and sadists. "You're right. No one was that keen to do him. He was a hard sell. Even my publishers questioned him, because he's not an obviously sympathetic candidate. All people know is that his name is synonymous with pillage and destruction. And he had few redeeming qualities. He wasn't even nice to his dogs. But in terms of achievement, he is the greatest rags-to-riches story of all time. He started with nothing. He was abandoned and left to die. So to achieve what he did, it struck me, was pretty impressive."

I almost have to drag out of Iggulden details of the serious and detailed research trips to Mongolia he has done on Genghis Khan and his successors, Ogedei and Kublai Khan (there are two more instalments to come in the "Conqueror" sequence). He prefers instead to tell me about a more recent experiment he made his wife carry out. "I needed to know for the book whether you could be stifled with a pillow. So I asked her to stifle me. We'd worked out a code – I would tap my hand if I was about to pass out. And do you know what I found was that, as long as I kept calm and kept breathing through the cloth of the pillow, I was fine, even when she was pressing with her whole weight."

It is an experiment that he won't, he assures me, be including in volume two of The Dangerous Book for Boys – if that ever happens. He currently has no plans. You do get the sense, though, that writing feels like one big adventure for Conn Iggulden. Perhaps, given how long he struggled to get paid for what he does today, that is inevitable. And somehow that enthusiasm and joy is transmitted to his readers, which may explain his phenomenal success. "My wife says that the one problem with being published," he reflects when I suggest this to him, "is that now I no longer have a hobby."

The extract

Empire of Silver, By Conn Iggulden (HarperCollins £18.99)

'... Both men were brothers to the great khan, uncles to the next. They were generals of proven authority, their names known to every warrior who fought for the nation. When they reached the gate, a visible ripple ran through the ranks of men, vanishing into darkness. The bondsmen halted around their masters, hands on sword hilts. On both sides, the men were strung as tightly as their bows'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments