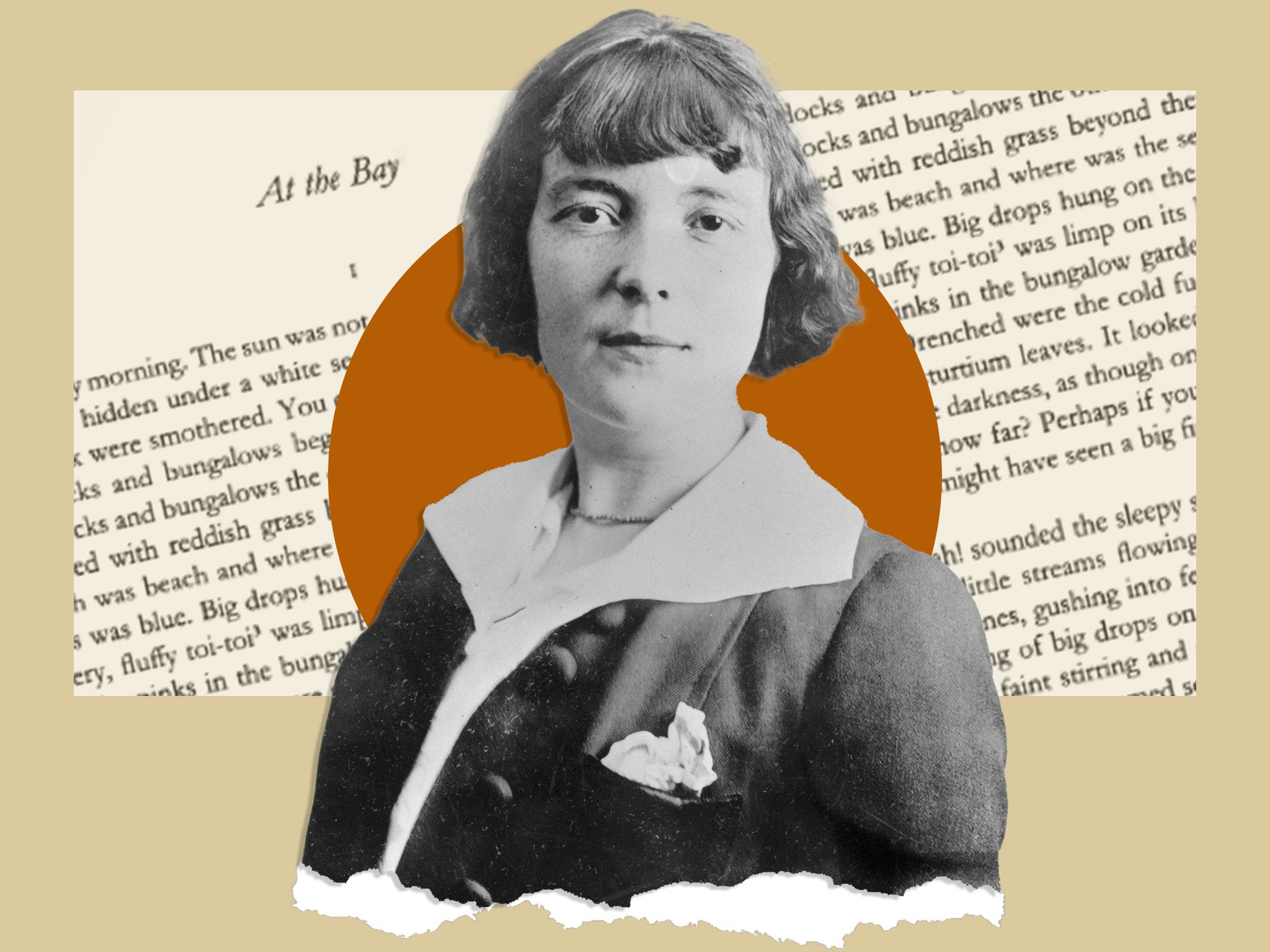

‘She was on a par with Joyce, Lawrence and Woolf’: Katherine Mansfield’s new biographer on the writer’s legacy

Author Claire Harman talks to Jessie Thompson about the short story writer’s wild life and why she should be considered among the modernist greats

Katherine Mansfield was the writer who didn’t sit still. In the century since her death, stories, memories and anecdotes have been passed down in which she seems akin to a human propeller. My favourite: her race to the finish line as she wrote her magnificent 1920 short story “The Daughters of the Late Colonel”, in which two spinsters collect themselves after the funeral of their controlling father. As she neared the end of the story, Mansfield, scared of dying – she had been diagnosed with TB in 1917 – wrote speedily, like a spinning top, at one point even stopping halfway up the stairs to write her next sentence. At 3am, the story was finally finished – but she didn’t go to bed; instead, she immediately wanted to read it to her friend, Ida Baker, who was living with and nursing her at the time.

“Once she got going on something, she was quite obsessive about it,” says Claire Harman, the author of All Sorts of Lives: Katherine Mansfield and the Art of Risking Everything, a new biography that recounts this incident. And Mansfield needed to be – she was to die in 1923 at just 34, two years after “The Daughters of the Late Colonel” was published. Even her death, 100 years ago this week, seemed to have a unique vitality – Harman’s biography begins with Mansfield running up some stairs, which prompted “a great gush of blood” from her mouth that led to her dying minutes later.

Born in Wellington, New Zealand in 1888, Mansfield lived a life that was packed with wild, and sometimes dark, incident. She was a voyager, moving to London for her education, and later hopping around Europe, making friends – and finding rivals – as she went. She had headlong love affairs with both men and women, and her first marriage was a sham; her second, with the writer John Middleton Murray, was immortalised in fiction as Gudrun and Gerald in DH Lawrence’s Women in Love. (She later told off a Romanian princess for consorting with her husband: “Please do not make me have to write to you again. I do not like scolding people and I simply hate having to teach them manners.”) Like Sylvia Plath, another born writer, she kept a journal in which her mind, unfiltered, came alive on the page. In an entry that bristles with energy, written on her 34th – and final – birthday, Mansfield outlines her hopes for her life: “I want so to live that I work with my hands and my feeling and my brain. I want a garden, a small house, grass, animals, books, pictures, music. And out of this, the expression of this, I want to be writing.”

Although she wrote more than 100 stories, as well as her journal, many reviews, and lots of entertaining letters, Mansfield’s literary reputation remains somewhat slight. “I think if she’d have written a couple of novels, as well as all of these short stories, she would have had more critical respect during those years where literature was being set up as a canon,” suggests Harman.

Last year’s celebrations of the birth of modernism in 1922 all but missed her out, even though, as Harman says, “she was completely on a par with, and working at the same time as, James Joyce, DH Lawrence and Virginia Woolf” – all writers that she knew personally. But – long overdue – she is finally emerging as more of a forerunner than a footnote, with a legible influence on contemporaries such as Woolf, and writers that followed, from Evelyn Waugh to Alice Munro to Tessa Hadley. (Upon learning of Mansfield’s death, Woolf wrote in her diary that there was no point in writing – “Katherine won’t read it”.)

If Woolf was your well-read friend who sipped cups of tea, Mansfield was your mate who made you drink a bottle of wine on a school night and told you things you couldn’t wait to repeat. Her stories are daring, unpredictable, threaded with the hum of life. Take the opening of her short story “Bliss”, in which 30-year-old Bertha Young seems to be almost bursting with joie de vivre. “What can you do if you are thirty and, turning the corner of your street, you are overcome, suddenly, by a feeling of bliss–absolute bliss!–as though you’d suddenly swallowed a bright piece of that late afternoon sun and it burned in your bosom, sending out a little shower of sparks into every particle, into every finger and toe?” It’s a description of rapt contentment that shimmers – only we are later to discover, in the kind of slow revelation characteristic of an Ishiguro novel, that Bertha’s existence is far from blissful.

There is a sense of quiet revelation to her stories that flits freely between horror and liberation. The half-finished sentence at the end of “The Garden Party”, in which a violent death ruins a genteel social affair. The mysterious sound of crying that closes “Miss Brill”, after its lonely protagonist returns her fur scarf to its box. The fleeting absentmindedness in the last glimpse of “The Fly”, where a father has distracted himself from his grief by playing God with a fly and an inkpot.

If Woolf was your well-read friend who sipped cups of tea, Mansfield was your mate who made you drink a bottle of wine on a school night

Importantly, notes Harman, Mansfield “never tries to write like a bloke”. Even in a world where women writers were rare, she unapologetically claimed the role of creative artist. “She’s so incredibly honest with herself. She was accused by other people of being a mask wearer and socially quite a slippery character. That’s completely intentional. She was playing the room every time,” Harman explains. She also had to deal with specifically female issues – the “gynaecological disasters”, in Harman’s words, that came from contracting gonorrhoea, and, later, becoming the subject of blackmail from a former lover possessing private letters. (She was to give Polish émigré Floryan Sobieniowski £40 to destroy them in 1920 – her entire advance for her next collection of stories.) It was an age in which she suffered, Harman says, for “just being a sexually active female”.

Claire Tomalin, the last to pen a major Mansfield biography before Harman (her book, A Secret Life came out in 1987), described Mansfield’s life as “painful, and it has been a painful task to write about it”. It is a vibrant life, and not an unfulfilled one – but it is tragically shorter than it should have been. There is, too, the challenge of lost material – what were in those letters Mansfield was blackmailed for? Having lived with TB for six years, Mansfield knew she was battling under the shadow of death, which makes her greatest lesson all the more powerful: she knew how to savour her days. “What she does is a kind of super mindfulness. She really wanted to just keep looking at things, keep enjoying things, just looking, looking, looking, writing things down,” says Harman. “That wonderful, incredible, life-affirming – and very useful to a reader – thing that Mansfield does, which is to show one how her imagination works, and how limitless and fecund and comforting the imagination is for anybody.”

Like many who are driven by an urge to write, Mansfield, with all her gifts, often felt she was coming up short, not quite getting there. “There’s no point where she ever becomes complacent. She’s very critical of herself all the time,” says Harman. “Something like ‘The Garden Party’, that people think of as a classic, she writes afterwards, ‘it’s not quite right. I could do better’.”

But there she was wrong. Writing on the stairs, conjuring up bliss, telling off princesses: we might wish for more Mansfield – but we could hardly wish for better.

‘All Sorts of Lives: Katherine Mansfield and the Art of Risking Everything’, published by Chatto & Windus, is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks