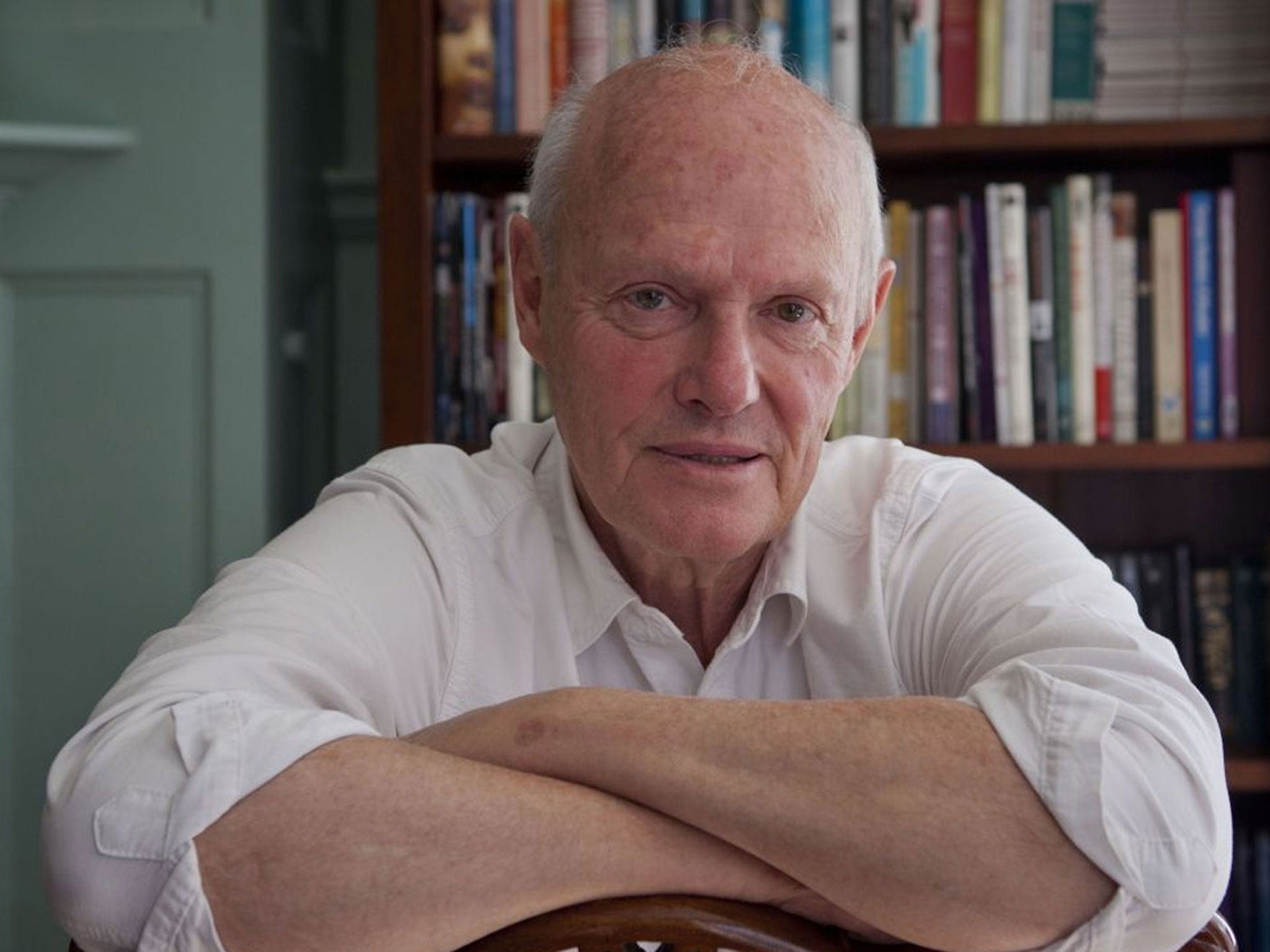

Justin Cartwright interview: We each have our cross to bear

Justin Cartwright tells Max Liu how his new historical novel tweaks the genre's formulas

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Anybody who wonders whether novelists can keep up with an accelerating world should read Justin Cartwright. The South African-born author, who settled in England more than 40 years ago, consistently captures the zeitgeist and his new novel is timely even by his standards. "I like to think I'm on top of things," he says, "but events move so fast that you risk being outdated by the time the book is printed." That certainly hasn't happened with Lion Heart, an ambitious meditation on history and fiction, which explores medieval and modern religious conflicts and some of England's favourite myths.

Cartwright's previous novel, Other People's Money, (2011), got to grips with the financial crisis by presenting bankers not as bloated caricatures but as individuals who were "deluded like the rest of us". He worked "damned hard" on Lion Heart and his publishers are comparing it to Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose. "I thought I'd write a massive Postmodern novel about Richard the Lionheart and Robin Hood," he says, "but it turns out they couldn't have met because the first mention of Robin Hood appears 60 years after Richard died."

The novel got going for Cartwright when he added the modern-day story of Richie Cathar, a young writer who visits Jerusalem to research Richard the Lionheart's hunt for the True Cross, upon which 12th-century Christian crusaders believed Jesus was crucified. Richie falls in love with Noor, a beautiful journalist who vanishes in Egypt after the Arab Spring. He becomes embroiled in a mystery, which involves kidnappers, spooks and priceless relics, as he tries to discover what happened to Noor.

If the plot sounds worthy of Dan Brown, that's because Cartwright wanted to "tweak the formulas" of genre fiction: "At first, Richie's role is uncertain. Is he writing the novel or is he the narrator of a novel written by me? It becomes clear as the story develops but the invented medieval sections ... are written in a deliberately florid style. You can't believe anything that's written in an historical novel and yet the author's job is always to create a believable world that readers can enter. It's especially so, I think, for writers of historical fiction."

On the page and in person, Cartwright is an assured presence. His characters inspire less confidence and he's interested in the human weakness for myth-making: "Jerusalem is enchanting but it's the capital of delusion, extremely dense in opinions. I tried to write as if I was mirroring Richie's quest, trying to discover truths about the cross and about his dead father." Cartwright agrees when I observe that he often depicts sons who are contending with fathers' legacies but his admiration for his own father is evident: "My dad was editor of The Rand Daily Mail, an anti-Apartheid newspaper in Johannesburg, at a time when you could be imprisoned and left there. He was summoned by police and told to bring his toothbrush. They also delivered a dead dog to his office. I sometimes think that what I understand, that English people don't necessarily understand, is that ideas have consequences."

Cartwright left South Africa in the late-1960s, when he won a scholarship to Oxford University, an experience which a character in Lion Heart describes as "like waking up in heaven". After graduating with a BLitt, he worked in advertising and directed documentaries, before his first literary novel, Interior (1988), was published. He's since written 11 more, including In Every Face I Meet (1995), which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Researching Lion Heart involved a welcome return to Oxford: "I regard myself as a realist and being down in the Bodleian Library, seeing how they scan and research historical documents, was interesting," he says. "I didn't anticipate making discoveries but I wanted a sense of what it might be like. I take John Updike's view that you need a bit of carpentry when you write a novel."

Fiction, for Cartwright, makes sense of events. "Historians and journalists always have agendas," he explains, "but if I want to find out what's going on in South Africa, I read Nadine Gordimer or John Coetzee because they offer novelistic truth."

So was writing about Richard the Lionheart a way of indirectly examining contemporary England? After all, when Richie returns from the Middle East, he works for a eurosceptic peer who's determined to discredit "les grands fromages" in Brussels. "His attitudes were borrowed from a Lord who I had lunch with," says Cartwright. "It's odd the way that Richard the Lionheart has been appropriated because he wasn't really English. The myth bears no relation to facts. Some people still believe England is supremely blessed. I don't buy that but it's a country I love. Although I didn't like those vans driving round recently, telling illegal immigrants they'd be rooted out."

Readers will relish the way that Cartwright embellishes the True Cross legend but they must solve Richie and Noor's mysteries for themselves. Unlike Dan Brown's potboilers, Lion Heart rewards careful reading and reveals parallels between its medieval and modern protagonists. "Richard the Lionheart wasn't really interested in his dynastic wife, Berengaria, and there's a suggestion that he treated women captives very badly," says Cartwright. "A journalist told me that when she read the scenes where Richie gloats about an ex-girlfriend's misery, she thought: 'Oh my god, this is Martin Amis.' I'm not an especially male novelist but I think men are better at writing about men and the same is true for women. Reading Saul Bellow is a revelation but he can't write women. There are exceptions, like Marilynne Robinson's Gilead, but generally I think it's true."

At the moment, Cartwright is writing a play, which he hopes to see performed in Cape Town, but he isn't sure what lies ahead for his homeland. "When [Nelson] Mandela dies, the country won't fall apart because he's gone. But it might fall apart because the government is corrupt and incompetent."

He's more certain about his own future and looks mildly disappointed as I ask if there will be more novels: "Absolutely. The nature of writing obsesses me. It's not on the sidelines of life, it really is life. Books change the world in small increments, by marginally altering our perceptions. You might intuit something but, until you read it, you don't necessarily know that you know it. I never know what I think until I write it down."

Lion Heart, by Justin Cartwright

Bloomsbury, £18.99

'I was named Richard because my father loved Richard I of England, the Lionheart. But I am usually called Richie. My father's surname – and mine – is Cathar, which he adopted when he was at Oxford in 1963 and often under the influence of drugs. Our family name was previously Carter, way too mundane for my father'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments