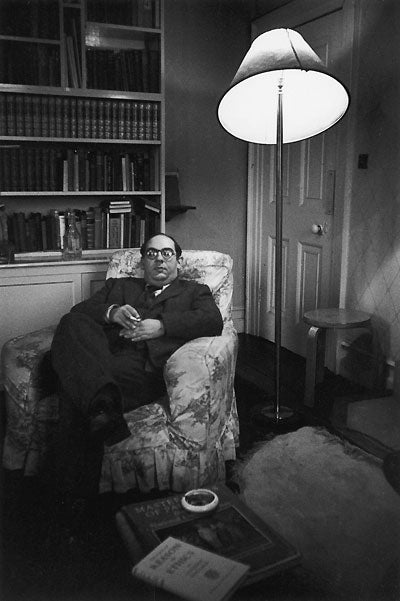

Isaiah Berlin: The free thinker

The philosopher and Cold War critic was born 100 years ago. Nick Fraser explains why his ideas of liberty are more relevant than ever

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Next week the faithful will assemble to mark the centenary of the philosopher Isaiah Berlin. He'll be celebrated in Jerusalem, which he loved, in Harvard where he taught; and in Oxford, which, in his rumpled Savile Row suits and academic floppy hats and gowns, he seemed to represent spiritually, as a totem. A statue is planned for Riga, in the Baltic, where he was born.

There are many good reasons to commemorate Isaiah Berlin's life. Like many Jewish émigrés of his generation settled in Britain, he proved capable of reinterpreting the national culture. As a broadcaster and lecturer, he performed without notes, stringing from idea to idea with the precarious ease of a man on wire in the wind. He was a dinner-party superstar. "A fascinating figure, bubbling continuously with energetic vitality, he is becoming a legend," American Vogue reported gushingly in 1950. "He talks all day and all night at astonishing speed. His knowledge is truly terrifying, ranging from Russian literature to the history of political thought."

But I have my own reasons for commemorating Berlin. From the late 1970s onwards, I've carried paperbacks of his work when travelling in the old Soviet bloc, or the states newly created after the fall of Soviet communism. He understands what these places became as if he had lived through the Stalinist catastrophe. But he also describes our own modern plight, too. What he says about liberty seems to speak profoundly to our own apathetic moment. Berlin says, again and again, that freedom isn't a bonus or an accessory, to be taken up or jettisoned at will. "Everything is what it is," he concludes. "Liberty is liberty, not equality or justice or culture, or human happiness or a quiet life."

Berlin's status as contemporary sage is now assured, and his work has been republished, reclaimed from neglect; but this wasn't always so. In the 1960s, he was thought to be passé, a defender of a corrupt status quo. Academic critics have always found him too easy to understand. These days Berliners enthusiastically applaud his contribution to liberal "value pluralism," and there has been a wrong-headed tendency to enlist him in the dismal ranks of multiculturalists.

My own Berlin is an impassioned, sometimes awkward figure, stumbling over his words in an effort to define exactly what he meant by being free. Berlin's half-forgotten role as Cold War sage and combatant fascinates me, because this is where his passions surface.

At first sight, Berlin's highly developed sense of ambiguity would seem to disqualify him as a polemicist. He was, in fact, just as effective as George Orwell or Arthur Koestler when it came to trashing Soviet communism,.

One of Berlin's most famous essays, "The Fox and the Hedgehog", contrasts those who know a little about a great many things with those whose minds, stubbornly focussed, comprehend just one thing. Berlin liked to represent himself as a fox, but in relation to what he cared about, he was a hedgehog. Beneath the camp Noël Coward accent and rapid-fire intellectual rapper locutions were steely convictions.

Berlin witnessed Bolshevism at first hand as a child, in revolutionary Petrograd. Aged 11, he wrote a rather good short story in which the villain was a Bolshevik murderer. By contrast, the England that he encountered as a schoolboy appeared a wonderful place – a messy liberal utopia dedicated to tolerance and the pursuit of difference.

Berlin was educated at St Paul's, reading philosophy at Oxford. He was the first Jewish Fellow of All Souls when the college could still claim to be at the centre of British intellectual life. The worldly side of Berlin came to the fore, with weekends spent at the Rothschilds and other posh friends. But Berlin's stubbornness was also in evidence through principled opposition to appeasement. He wasn't afraid to take on the worthies who assembled each weekend in college to discuss how Europe could be handed over to Hitler in order to avoid a war. His big break came when he went to America in 1940, writing a confidential weekly letter than combined in equal parts his talent for gossip and political analysis. Many, including Churchill, looked forward to their weekly doses of Berlin. Churchill indeed invited the songwriter Irving Berlin to lunch under the impression that he was the author of these weekly dispatches.

In 1946, Berlin was able to wangle a posting to Moscow as First Secretary, with the task of analysing the postwar mood in Moscow. In Petrograd he managed to meet the poetess Anna Akhmatova, who seemed to incarnate the old Russian intelligentsia, and who had somehow survived both the Great Terror and the wartime starvation. Berlin was famously uninterested in sex (he was a virgin until the ripe age of 42) but some sort of charge passed between them as they talked through the night in an empty, derelict palace.

It was the formative moment of Berlin's life. As the philosopher John Gray says, Berlin was born into Russia's social-democratic age. "That nurtured a particular kind of liberalism – not related to individual rights, but about freedom against authoritarianism." Berlin's assaults on Stalinism are remarkable for their sustained passion. As a young man he'd written about Marx, and he understood as well as Orwell the way in which ideas could be twisted out of shape to justify tyranny.

Berlin's most influential work remains "Two Concepts of Liberty", based on an address he gave at Oxford in 1958, when he was made Professor of Social and Political Theory. In the lecture Berlin distinguishes between old-style, traditional negative liberty, in which people are left to themselves to work out their own destinies, and the newer positive liberty, in which they are offered participation in a Grand Collective Project offering identity and self-realisation. To the casual reader, Berlin can seem merely to be engaged in an urbane, high-speed rap through ancient and modern ideas of liberty trying out various notions in order to see how they suit the age.

This is indeed how the former prime minister, Tony Blair, appears to have interpreted the text, when in 1997 he wrote to Berlin (shortly before the latter's death) suggesting that positive liberty, "despite its depredations in the Soviet model", had much to commend it. Blair was fooled, as others have been, by the elegant Berlin prose. Where liberty was at stake, Berlin was never even-handed. He was a hard-line liberal seeking to save the tradition from those who would destroy it. It's a shame that Berlin was too ill to answer the Prime Minister's letter.

As the historian Tony Judt explains, Berlin inhabited a context where there was no middle ground. "You collaborated with Stalin, or you didn't," he says "This aesthetic of choice informed most intellectuals' understanding of their world." Liberal intellectuals during the Cold War thought of themselves as fighting Soviet communism, and many were prepared to take money from the CIA. Berlin kept his distance. He spent the Cold War in Oxford, reading and lecturing about intellectual history. His contribution was to explain how the beliefs opposed to liberal democracy had come into existence. Berlin specialised in digging out totalitarian tendencies among such sages as Rousseau, whom he described as an "intellectual guttersnipe".

From Berlin's recently published voluminous 1950s letters, however, it's clear that he was fully engaged in its cultural battles. Berlin was pro-American, Zionist. He did block the appointment of those whose views he disliked, including the biographer of Trotsky, Isaac Deutscher. Invited to dinner in Washington to meet John F Kennedy, he gave the president an improvised lecture on the nature of Soviet power on what turned out to be the eve of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

There can be no doubt that Berlin maintained his links with MI6. His reaction when muck-rakers revealed that the magazine Encounter, for which he wrote, was funded by the CIA, was one of unconvincingly simulated surprise. He appears to have been annoyed that the cover was finally blown. If these are failings they must be set against his passionate, disinterested sponsorship of writers like Pasternak and Solzhenitsyn. Berlin was overcome by the sight of those with the courage to resist what he believed was the worst tyranny the world had seen.

Sitting with biographer Michael Ignatieff, watching as the Berlin Wall was ripped down, he wept tears of joy. One of the most eloquent things he wrote is a short piece for Granta in 1990, after the fall of communism, when he was 80. "My reactions are similar to those of virtually everyone I know; or know of – astonishment, exhilaration, happiness. When men and women imprisoned for a long time by brutal and oppressive regimes are able to break free, at any rate from some of their chains, and after many years know even the beginnings of human freedom, how can anyone with the smallest spark of human feeling not be moved?"

It's not a fashionable view, but I'm impressed by the consistency and passions of Berlin and his fellow Cold Warrior liberals. No-one would wish to see a return to the Cold War national-security states. But it's hard not to feel that the post-Wall era hasn't lived up to expectations. If liberal democracy has triumphed everywhere, some of its features are less than appealing.

Among Berlin's greatest, most perceptive fans is the playwright Tom Stoppard. The Coast of Utopia is a nine-hour tribute to the 19th-century members of the Russian intelligentsia revered by Berlin. But Stoppard's Rock'n'Roll depicts Britain as a country that has betrayed its own liberal heritage. "Don't come back, Jan," an émigré character tells the Czech hero. "This place has lost its nerve. They put something in the water since you were here. It's a democracy of obedience. They're frightened to use their minds in case their minds tell them heresy. They apologise for history. They apologise for good manners. They apologise for difference. It's a contest of apology..."

In Prague, I was struck by the levels of local cynicism while reading about the fall of our political class. Czechs, young and middle-aged, appear as discomfited by their democracy as we are, reviling the Czech political class. I wondered what Berlin would think of the apathetic state in which so many Europeans find themselves.

Berlin's own utopia was assembled from imperfections. He liked to quote Immanuel Kant's observation "From the crooked timber of humanity no straight thing can be made." (It was in fact a misquote, like many Berlin-isms.) His grasp of the ironies of history made him into a sceptic, reluctant to believe in any form of dogma. Berlin believed you must be, and stay critical.

But Berlin was also lucky in many ways. He lived and wrote at a time when enemies of the open society were easy to identify, and he was supported by an elite sharing his views. Nowadays the enemies of open society are less easy to categorise, and many of them come not from the ranks of those formally dedicated to our destruction, but from within our own societies. People don't always choose to defend freedoms. They may indeed decide that the illusion of security is better than liberty. Or they may believe that modern politics is so remote that all effort must prove futile. In Britain, in the United States and in most democracies, large minorities appear to hold such view. Is there any reason why we should believe that people, given the opportunity to choose, make good choices?

Berlin would have answered that we're doomed to live among conflicting ideas of how to live. Freedom isn't pleasure or security, it isn't the accumulation of goods, or any number of things that we enjoy.

Apathy may be one of the consequences of a liberty long taken for granted, or indeed part of the crooked timbering. But freedom alone makes it possible to choose, for good or bad; and for that reason, freedom does matter. That's what Berlin ended by saying in almost every word he wrote, and it is why he still matters to us.

The second episode of 'Hearts and Minds', presented by Nick Fraser is on Radio 4, on 1 June, at 8pm. Among the books recently published on Berlin are 'The Book Of Isaiah, Personal Impressions of Isaiah Berlin', edited by Henry Hardy, The Boydell Press, £25, and 'Enlightening: Letters 1946-1960', edited by Henry Hardy and Jennifer Holmes, Chatto and Windus, £35

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments