Irvine Welsh on Dead Men’s Trousers: 'I like to get the psychology right. I like a book where it feels like you're locked in a room with one of them'

Renton, Begbie, Sick Boy and Spud, are thrown together once more, older, and perhaps wiser, in Welsh’s twelfth novel, 'Dead Man’s Trousers' – but, the novelist says, it's the end of the road for the 'Trainspotting' gang

“Choose a life. Choose a job. Choose a career. Choose a family. Choose a fucking big television. Choose washing machines, cars, compact disc players and electrical tin openers…”

It’s a monologue most beyond the millennial divide can instantly recall from reading Irvine Welsh’s 1993 novel, Trainspotting, narrated by a rugged, youthful Ewan McGregor in the opening of Danny Boyle’s 1996 now cult-classic film or seeing reproduced on posters and other adolescent paraphernalia during the decade after Trainspotting was published.

As much immortalised in Britpop culture as making comment on it, Welsh’s gritty, groundbreaking first book about a group of Scots in 80s Edinburgh battling boredom and heroin addiction, stuck in housing schemes amid societal decay, navigating brittle friendships and betrayal set a new tone in fiction – and subsequently film and theatre – that is still felt today. Released this week is Welsh’s twelfth novel, Dead Man’s Trousers, where the infamous crew from that first set of stories, Renton, Begbie, Sick Boy and Spud, are thrown together once more, older, and perhaps wiser, if only in terms of honed survival skills.

Hailing from Leith, Edinburgh, Welsh’s signature Scottish dialect, skilfully brought to life in his phonetically-written texts, is very much present in this latest instalment, as Renton’s opening thoughts display: “Those eyes. They fry my insides. Make the words I want tae speak evaporate in the desert ay ma throat.” Though as I speak to the author from Miami and he describes sun streaming onto his balcony, just minutes from the ocean, he seems removed from his native land or the dark, grey Britain that exists in his books. Having finished substantive work on Dead Men’s Trousers 18 months ago, there’s a further sense of detachment from his imminent release: “By the time a book comes out you’ve forgotten all about it because you’re working on something else,” says Welsh. “That’s the strange thing about being a writer; you’re always living in a different world to everybody else.”

In his intervening novels since Trainspotting, Welsh has periodically returned to its now famed gang, interweaving the different worlds he creates into something of an amorphous fictional universe, with the general thread of a preoccupation of sub-working-class and drug cultures existing on the fringes of, yet also relevant to, mainstream society. 2001’s Glue revisited some of the characters as well as the locations, 2002’s Porno formed a sequel of sorts, 2012 Skagboys a prequel, while 2016 novel The Blade Artist pursued a distinct storyline with character Francis ‘Franco’ Begbie.

I’m keen to hear from Welsh if he can pinpoint what is was about these four figures from his first novel that continue to preoccupy him: “They’re quite memorable. They tend to gatecrash, they tend to keep coming back,” he tells me. But also they have captured the imaginations of so many, that garnered such empathy and disgust in equal measure from those that encountered them whether via page, screen or stage.

“I think it’s because they’re archetypes,” he suggests. “Everybody knows versions of these people. Maybe not quite as extreme versions. But everybody knows the compulsive, hypersexualised individual, the sort of cynical intellectual, a psychopath, a lovable loser.”

Crucial is the writer’s skill for drawing characters that may not be likeable but are impossible not to connect with: “I like to get the psychology right. I like a book where it feels like you’re locked in a room with one of them. They’re sitting on the next bar stool, next to you on the bus. You might not necessarily want them there. But they’re there anyway. There are in your face, you can feel their hot breath on your neck. I like the immediacy and intimacy of that kind of writing. So I always strive to create characters that so are so vivid and real they actually exist off the page.”

As a result, what can appear at times as moral depravity or despicability reveals itself rather as an extreme version of situations we all meet over a lifetime: “If characters are well drawn, you recognise the psychological truth in their behaviour. You remain invested in them no matter what they do. As long as you see them suffer the consequences – no one gets out scot-free really.” In that way, Welsh sees the three main books as a tackling a kind of “Holy Trinity” of universal themes of humanity: “A big theme of Trainspotting was betrayal. Porno was about revenge, Sick Boy and Begbie’s revenge on Renton. This book is about attempts at redemption, Renton to the best of his abilities trying to atone for his sins. We all experience these things and if we’re lucky we might get to some kind of redemption. Not for just the big horrible things that we’ve done but for the little things. The little snide things we have with each other. You get to that point that you realise life is too short and you want to heal. Reconciliation in some ways is about people making sense of their lives.”

Beyond an emotional resonance, Welsh also reads a metaphor for economic and societal shifts from his work that hits a nerve with readers: “It’s about what human beings do when they’re made redundant. We’re in a long haul transformation out of industrialism into a kind of conceptualism where it’s hard to monetise anything. It’s hard to make a living out of anything because technology is taking over. The old industrial working class these guys come from were the first generation to have to face up to this kind of thing. This existential question which is now haunting everyone. The middle classes and even the elites are having to answer the same questions the people who were working in factories and on docks and all that were having to ask themselves years ago. Basically, what is the point of me?”

And while times have moved on since he first gave birth to the Trainspotting-scape and the characters themselves have aged, for Welsh, many of the same themes linger on: “These guys are really in the same position that they were. They’re in different sectors of the economy, entertainment and personal services from DJs to prostitution to visual art. But they’re still trying to scam their way through using their wits like they were back in the day. Which is kind of everybody to an extent now there’s no real job security or employment security. Everybody’s in the same boat.” It’s a view borne out of his own take on our 21st-century relationship to work and the economy: “Three of them at least are superficially doing OK but they’re still beset with this crisis of having to work all these hours and do all this stuff to make a living while feeling that life is happening elsewhere. Particularly Renton: he is perceived as successful but he is on planes and in hotels, never seeing family or friends. It sounds like an incredibly glamorous life but it’s not, it’s a terrible life. It’s a kind of high-tech serfdom really.”

Despite drawing a scathing commentary of contemporary life from his own work, the author is quick to emphasise political statement is not an end in itself, rather something “that comes out in the wash”: “It’s not something I’m thinking about consciously at all. All I want to do is tell interesting, humorous and maybe occasionally quite kind of shocking and dangerous stories. If you get memorable characters and then maybe get people starting to ask what is compelling them, start thinking about the state of the economy and society and how desperate things are after that then great... but it’s not really my concern. I’m not really interested in overtly writing about it, it just comes out in the mix.”

And so real are these characters, they really have taken on a life of their own: “They’re not really mine anymore. Not really the filmmakers’ or the people who adapt them to the stage or whatever. They belong to the world now. They’re just so out there in the culture.” In particular, the movie adaptations have launched the stories onto an international stage. And while the relationship between cinema and literature is not always an easy one, with the risk a writer’s work is overshadowed or undermined by attempts to put word to screen, for Welsh, it’s only been positive. In fact, he recalls it was 2017 movie T2: Trainspotting that really inspired him to write Dead Men’s Trousers: “A lot of it was working again with everybody on the Trainspotting 2 film. We had this week in Edinburgh and we were all sat down in this apartment and went through all the characters and the Porno and Trainspotting books again. I kind of got immersed back into it.”

He also holds a keen grasp of what makes translating books to screen work, evident from the international success of both the first and second Trainspotting movies as well as others such as 2013’s critically-acclaimed Filth starring James McAvoy: “With cinema you want to capture the spirit of the characters, story and themes. But you have to create something that stands alone and isn’t an attempt to create a book in celluloid. Because that would be stupid, they are different art forms. Films that are too beholden to a book tend to be quite messy to be honest. It’s important to be a bit hard and fast with it when you’re doing the screenplay.”

Does he expect this latest book to form the basis of a third movie? “Everybody likes a comeback but it’s always a third one that’s pushing it too far. Nobody remembers The Godfather Part III or Terminator 3. I can’t think of a great third film that anybody’s done. So I believe we would be really pushing it. It’d be a very audacious thing to try and pull off. You could really bring down the whole legacy with a bad third...”

What about another book? “Never say never. But this feels like a natural end for them, certainly as a group. I physically killed one of them off because it would have been too tempting for me to create scenarios to bring them back together. So I think that’s the end of the Trainspotting gang, so to speak.” But he wouldn’t necessarily miss the guys if this really were the end: “I’ve still got the option to bring them back as individual characters. Plus you’ve got a much less sentimental relationship with them as a reader would do for example because you see them as tools to create a story. You can’t be too sentimental. I’m writing a new book now and I’m creating a lot of new characters from scratch and that’s fun too, you know.”

He admits feeling the challenge of being a writer in this day and age, of staying relevant amidst a fraught pace of change: “It’s such a tough thing to do now, especially if you want to write something that resonates with what’s happening in the contemporary world. You run the risk of doing something that seems to be completely irrelevant as soon as it comes out. In some ways it’s easier if you’re writing genre fiction because you have these universal themes to address or there are certain rules and protocols, set relationships with the reader that you have to that you observe. People like myself, we’re in a strange position: it’s like trying to nail jelly to the wall, it’s shifting sand all the time.”

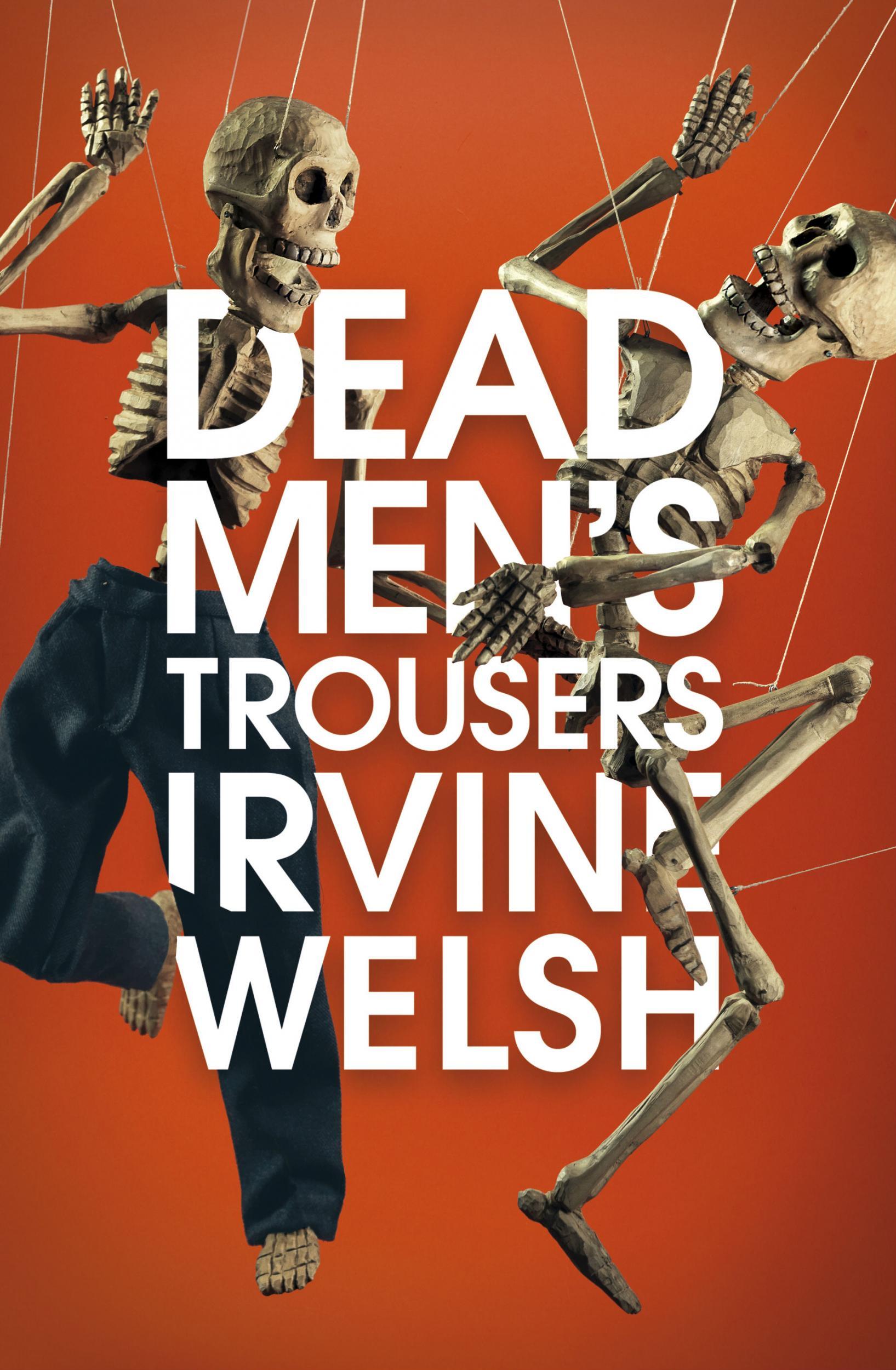

‘Dead Men’s Trousers’ is published by Penguin Random House on 29 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks