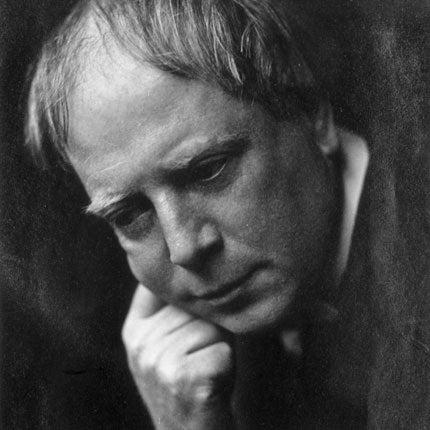

Invisible Ink: No 80 - Arthur Machen

Shockingly, a straw poll among young authors yielded just two recognitions of Arthur Machen's name in a group of 20.

In one sense, though, he was the Dan Brown of his time, creating elaborate Gothic novels predicated on the notion that beneath our ordinary lives is an unknown world of pagan ritual, mysticism, and spirituality.

Machen was born in a modest terraced house in Caerleon, Monmouthshire, in 1863, and introduced into occult circles by his wife, a rather bohemian music teacher. The first work that brought him public attention was the novella The Great God Pan, which tells of the seductive, sinister Helen Vaughan, who destroys young men's lives as she takes revenge for her mother, whose sanity was destroyed after coupling with the god Pan. Published in the early 1890s, the tale was denounced as degenerate. The Oscar Wilde scandal further tarnished decadent literature, and it became hard for Machen to find publishers for his subsequent works. In 1899, the death of his wife proved a devastating blow, and he took comfort in the exploration of further pagan myths by joining the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, although mysticism was a popular area of research for writers of the time.

At the start of the First World War, a legend surfaced that a group of angels had protected the British Army at the Battle of Mons. In fact, Machen had written a short story for The Evening News in London called "The Bowmen", but when the story ran it was not marked as fiction, and the Angels of Mons shifted from fantasy to reality, in the same way that the Pope started pronouncing on the so-called truth of The Da Vinci Code. Machen's finances were always perilous, and his connection to the Mons legend brought him some degree of financial solvency.

Remarrying, he began exploring the legend of the Holy Grail. His ideas surfaced in The Secret Glory, which suggested that the Grail had survived to the present day. His most influential work was The Hill of Dreams, in which a young man recalls a childhood in rural Wales filled with sensual visions from earlier times.

His disturbing stories have had a far-reaching influence on generations of post-war writers, and his belief that the British landscape retains the imprint of those who live in it has inspired writers such as Iain Sinclair and Peter Ackroyd to explore London's psychogeography. Tartarus Press has recently republished his best work.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks