Invisible Ink: No 167 - Day jobs of the detectives

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

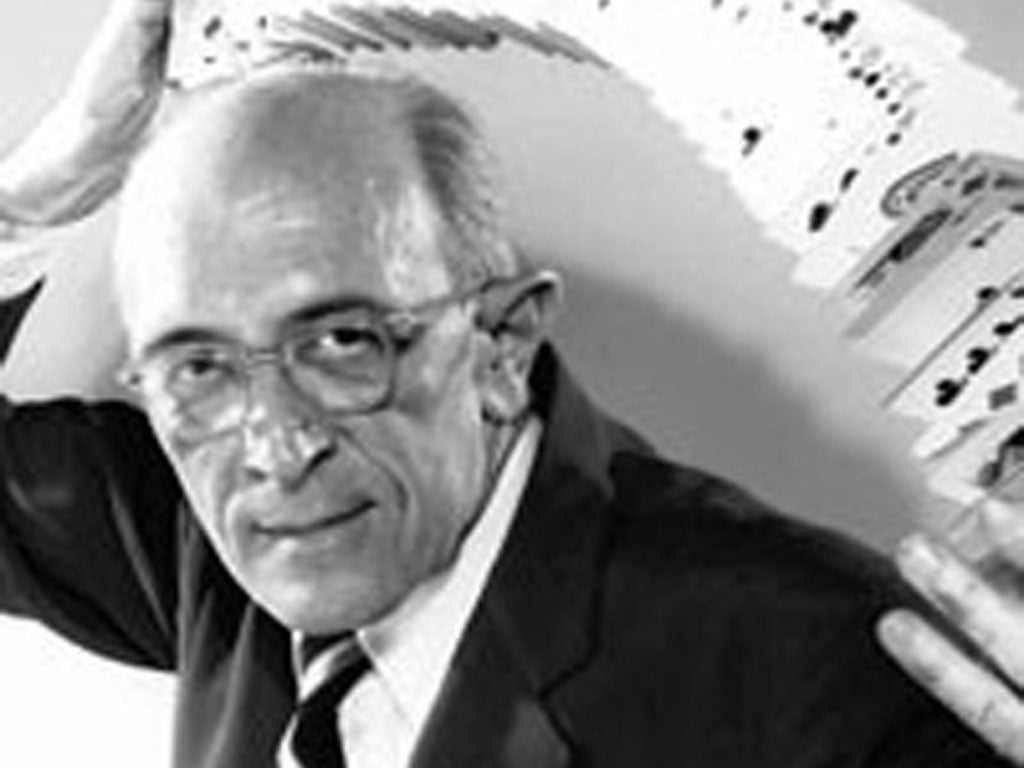

Your support makes all the difference.Clayton Rawson started studying to be a magician when he was eight. Later he put his magic skills into practice by penning the excellent Death From A Top Hat. His detective is self-taught, one of those louche interferers the police had no trouble allowing on to crime scenes in the inter-war period. The Great Merlini runs a magic shop, but his knowledge of optical trickery and mental misdirection alert him to the craftiness of thieves and murderers. He appeared in four novels and four collections of short stories.

This period of American mystery writing is more associated with hard-boiled fiction than the traditional butler-did-it Golden Age style of British authors, but Rawson's detective crosses that line, coming over as a sort of US Father Brown of magic. The murders are loopy – in one case involving a death in a locked room wherein the doors and windows have all been taped shut – but the solutions are fair and plausible. Rawson pitted his wits against readers, creating playful plots that fans could at least have a chance of solving.

Rawson became one of the four founding members of the Mystery Writers of America, who still present their annual Edgar Awards for excellence in crime writing. The Great Merlini featured in two movies and a television pilot. There were other magician detectives; Dakor the detective-magician appeared in 1940, and the TV show Jonathan Creek has a sleuth solving mysteries through his knowledge of illusionism.

From 1910 onward, many fictional detectives had day jobs that provided them with the skills for specialist investigation. They were chefs and antique dealers, civil servants, musicians, actresses, artists and mountaineers. Many were simply gentlemen of leisure, crimefighting being something you'd do if you were simply rich and bored. Both The Encyclopaedia of British Crime Writing by Barry Forshaw and Great British Fictional Detectives by Russell James catalogue these amateur sleuths.

One of my favourites is Colonel Henry Ponsonby, royal equerry, who turns up in H K Fleming's out-of-print thriller The Day They Kidnapped Queen Victoria. As the Queen's train to Balmoral is hijacked, HRH, Alfred Lord Tennyson, the Prince of Wales and his disreputable guests must be saved by Ponsonby from a dastardly Fenian plot. Like many of these forgotten tales, Fleming's volume is a virtual masterclass in good story construction, witty, erudite, and effortlessly charming, the antithesis of the kind of Grim Noir one-note thrillers that now dominate bookshelves.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments