Interesting object: The creation of the first part of the Oxford English Dictionary was particularly arduous

'One of its most notable contributors was in Broadmoor'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.People's knowledge of the history of the English dictionary is usually restricted to half-remembered gags from an episode of Blackadder. It's certainly true that Samuel Johnson laboured for decades on his Dictionary of the English Language (1755). But despite it being recognised as a momentous achievement, a group of London intellectuals – Richard Chenevix Trench, Herbert Coleridge and Frederick Furnivall – decided about a century later that it was high time for a new one. It would feature unlisted words, better quotations, better organisation, and would be called A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles.

If you've ever sat down and tried writing a dictionary, you'll be aware of what an onerous task it is. Trench, originally at the helm of the project, went off to become Dean of Westminster pretty swiftly. Coleridge, having assembled 100,000 quotation slips and having produced the first sample pages, promptly died of tuberculosis. Furnivall, taking up the reins, proved to be a poor motivator; volunteer readers tasked with copying passages from books on to quotation slips drifted away, and some slips went missing.

Furnivall eventually approached a Scottish grammar school teacher, James Murray, to reinvigorate the project. In March 1879, over 20 years after the idea was first conceived, a publisher was finally found; Murray was contracted by Oxford University Press to compile the new dictionary over what was envisaged to be a 10-year period.

Murray initially worked in a corrugated iron outbuilding of Mill Hill School, organising Furnivall's collection of quotation slips and appealing for readers to supply new ones. One of its most notable contributors, William Chester Minor, did so from Broadmoor Asylum for the Criminally Insane after having been convicted of murder. This subplot to the creation of the dictionary became a book in its own right – Simon Winchester's The Surgeon of Crowthorne.

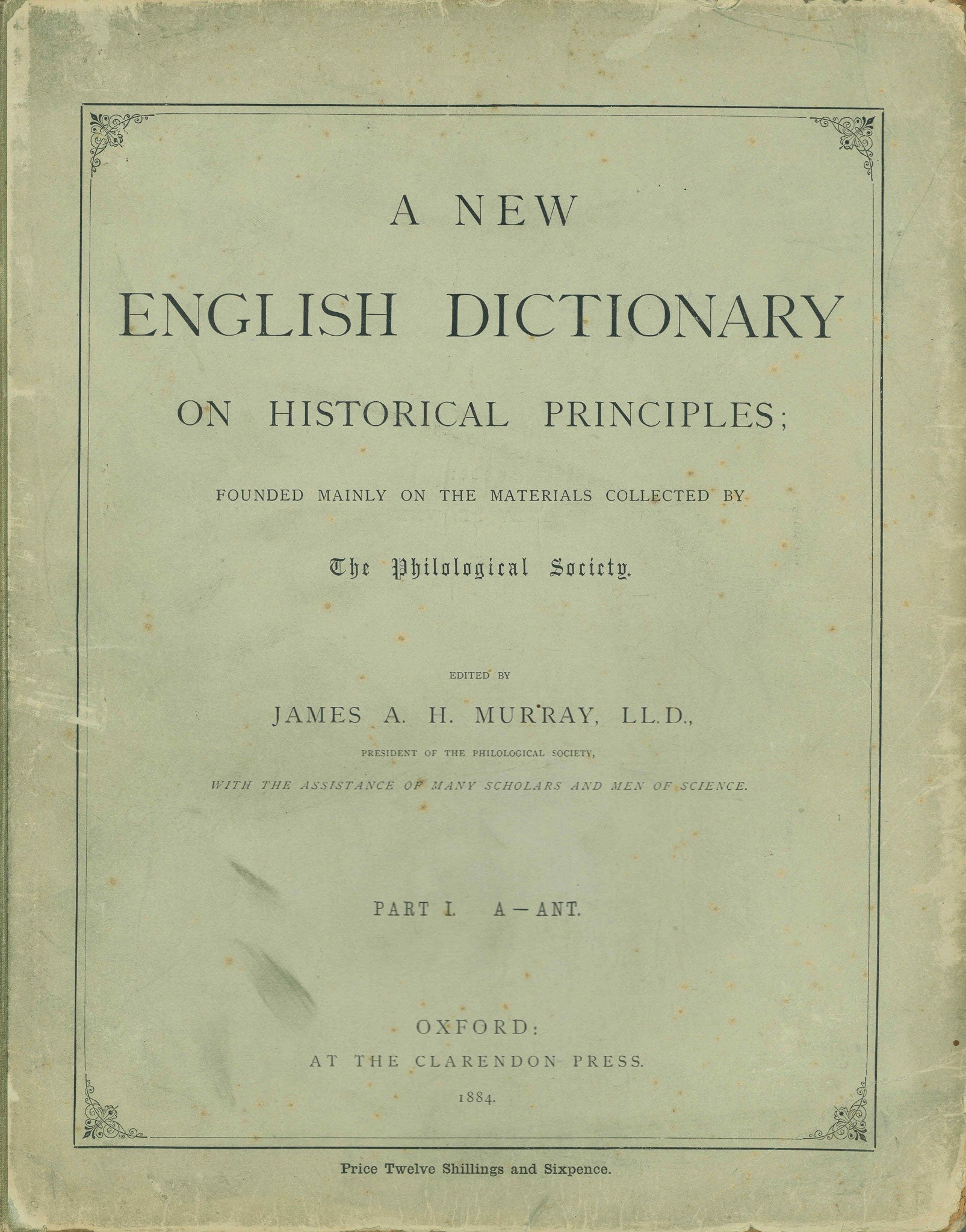

The first 'fascicle' of what would become the Oxford English Dictionary was published 130 years ago, on 29 January 1884 – although at this stage it still carried the New English Dictionary name. Nearly five years in the making, it contained 352 pages of entries (from A to -ant), cost 12s 6d and reportedly sold just 4,000 copies. Lacking recent examples of usage of many of the words therein, Murray and his colleagues were occasionally obliged to come up with their own (a practice long since discontinued, notes Peter Gilliver, OED's associate editor). While correcting proofs for the word 'a' by his wife's bedside following the birth of his daughter Elsie, Murray inserted this sentence: 'As fine a child as you will see'.

he final entry in the fascicle offers an explanation of how words like pageant and pheasant came to acquire a spelling ending in -ant, even though they derive from words in which there was no corresponding letter 't' (in these cases, the Latin pagina and phasianus respectively). Unfortunately, there's no room here to tell you what it is.

Thirty-six years after becoming editor, Sir James Murray – by now a knight – died of pleurisy. By this point the dictionary had only reached the letter T. When the last of 125 fascicles was finally published in 1928, the first edition had filled 15,000 pages and taken 49 years to produce. Only 39 years late – not bad, I suppose, for a dictionary.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments