Innocence of youth: How Paul Auster excavated his own past for his latest novel

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

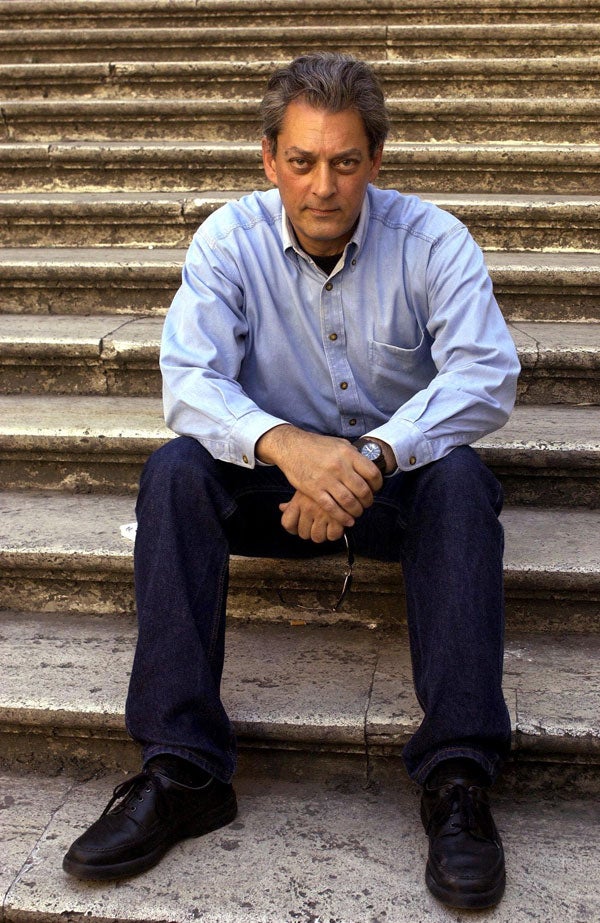

Your support makes all the difference.Paul Auster has just loped out of Sweet Melissa, an icing-sugar pink patisserie near his home in Park Slope, when the waitress who has buzzed around our table delivering bowls of soup and plates of quiche, rushes over to inquire after him. I imagine she is keen to share her views on his work - New Yorkers are fierce fans and he has a starry status in this literary square mile of Brooklyn - or admire his Gothic good looks. The most infatuated have been known to follow him across town.

Instead, she says: "Who is he? We've always thought he was just a regular guy... He comes here all the time, on his own, sits on this table..." she trails off, staring at the empty seat of this Sweet Melissa cipher-turned-Important Author. It's a case of mistaken identity not too far removed from Auster's first fiction, The New York Trilogy, inhabited by mysterious men with interchangeable names - sometimes Auster's own - who lose their identities down existential plugholes and spend the rest of the book trying to retrieve them.

Ever since that critical breakthrough in 1987, Auster has inserted aspects of himself, and those around him, in his work. A Paul Auster appears, fountain pen in hand, in a scene in City of Glass from The New York Trilogy; Sunset Park, his as yet unpublished novel, features Willa Parks, a woman who wrote to Auster when he was collecting real life stories for radio in 2001; Leviathan's Maria borrows from the life of the artist Sophie Calle; more confusingly, Auster once claimed the main character from the same novel was married to the heroine of his wife, Siri Hustvedt's novel, The Blindfold, in a transfictional romance; the instances of fiction-imitating-life-imitiating-fiction are numerous. These porous worlds have enthralled fans but left critics equivocating, with the meanest charging him of solipsistic game-playing.

Auster who is dark, towering - part matinee idol, part silver-screen villain - waves the criticism away. He has stopped reading reviews - "no good can come of it, I spare my fragile soul" - even the good ones, because they miss the point. He has reasons to be disgruntled. They call his work 'Beckettian' for its absurdist qualities. He disagrees. "I think my work is nothing to do with Beckett."

They say he's a postmodern master of meta-narratives, with his spools of stories within stories, but he cites the likes of Emily Brontë over Baudrillard as a source of inspiration.

Auster's literary career began haltingly, first as translator, then poet (he met Hustvedt at one fortuitous poetry reading) until he hit a wall in his late-20s. He switched to prose and publishing a memoir, The Invention of Solitude, before fiction. He makes no secret of using aspects of his biography to cross-fertilise his 15th novel, Invisible (Faber & Faber, 16.99). The year is 1967 and his protagonist, Adam Walker, is a 20-year-old Columbia student and opponent of the Vietnam War who goes to Paris for a "Junior Abroad Program" before coming back, disheartened, to work at New York's Butler Library.

To anyone who has read Auster's 1997 memoir, Hand to Mouth, Adam's life appears to replicate Auster's own year of '67, complete with the abortive year abroad and fear of the draft. Yes, he concedes, his early life gives Invisible its geographical signposting, especially the Paris of his youth, to which he has always retained an affinity. "I stayed in that hotel (in Saint Germain) with the U-shaped mattress that dipped in at the middle. It would be silly to deny that the book does not use parts of my life, but I was using it only as a springboard. Walker's story is not my story. "I draw on a year of my life when I was 20, in 1967 and '68. It's hard to explain the chaos of that time. The devastation of the Vietnam war in American Society. There was suddenly the prospect of the draft facing us... the race riots, the assassinations, the war, the war, the war. It was tumultuous, to be so young, but old enough to have a mind, and to take stock of what's going on."

War lies at its fringes, however, not its centre. As a story which delves into the "erotic cravings" of Adam's youth, it is a coming-of-age novel with an unexpected tale of brother-sister incest at its heart. Adam and his teenage sister, Gwyn, embark on a "grand experiment" a passionate relationship begun in adolescence which carries through into later years that is devoid of the guilt and dark perversion normally seen in incest narratives. Their love, ardent but ultimately doomed, is described in the tender, beguiling language of romance. "It was one of the most intense pieces I have ever written," he says. "It moved me to write it. I have no idea what other people will say about it."

But he may already have an inkling from one early reading. "Siri and I went to Brown University back in the Spring. I read the passage on the 'grand experiment' to a roomful of students. I heard a couple of nervous titters from the audience. After the reading was over, no-one mentioned it, they just said it sounded like a nice book, there wasn't a single comment about what I had read."

With this ordinary-world incest, Auster captures well the dangerously free-floating, experimental nature of early adolescent sexuality. "Very young people, either in early adolescence or a bit older, know so little about sex yet they are so horny. All kinds of things happen that nobody talks about."

Just as the reader is settling into the story Adam's reflections on his early romances, a cold-blooded murder he partly witnesses, his friendship with the older, urbane couple, Margot and Rudolf Born, the fiction is intercepted by the storytelling process, a classic pulling-of-the-rug from under the reader's feet that Auster fans should have come to expect by now. Adam's unfinished, abruptly halted autobiography, not unlike (dare I say it) Beckett's Krapp's Last Tape, written by him feverishly as an old man on the verge of death and sent in serial form to a school-friend, is not all it seems. Queue the entry of an "unreliable narrator"; it is blind alleys and puffs of smoke from thereon in. Auster's insists the answer to this trickery is not postmodern, but dates back to the 19th century.

"There were certain kinds of books I was attracted to as a young person, two jump to mind. Wuthering Heights and The Scarlet Letter. These fascinated me. You know full well these are fictions within fictions. The act of telling becomes part of the story. [Invisible] is an examination of how books get written, what a book is. I went where my nose was leading me. "

In spite of the games, there is an undeniable romance to Auster's fictional world, where serendipity and chance leads to blazing romances and intense mysteries; anonymous phone-calls are made and manila envelopes pushed under doors that lead ordinary, flawed men out of the shadow of anonymity to centre stage, if only to express their sense of failure.

In an interview with the Paris Review in 2003, Auster spoke about a project he undertook with National Public Radio, when 4,000 people wrote to him with "true stories that sounded like fiction", which could serve as a mission statement: "I wanted to prove that there's no such thing as an ordinary person. We all have intense inner lives, we all burn with ferocious passions, we've all lived through memorable experiences at one time or another."

His writing methods appear to have a charming, otherworldly romance, too. Ever since 1974, he has written with ink on paper before typing out the results on an old Olympia typewriter, paragraph by paragraph, correcting as he goes along. He eschews the Internet age Google, email and Skype ("what is that?", he puzzles). "I can't conjure up figures with my fingers poised on a keyboard. I need a pen. It's the physical gesture that unleashes the words."

He bills himself not unlike the waitress in the patisserie as a regular guy with simple requirements for a good life. "I don't want to do anything else except write, watch baseball games and be with my wife." It was baseball that led him to write in the first place, according to an account in The Red Notebook, when he is taken to a Giants game as a child and fails to secure an autograph of a player because he doesn't have a pencil. "If nothing else, the years have taught me this: if there's a pencil in your pocket, there's a good chance that one day you'll feel tempted to start using it. As I like to tell my children, that's how I became a writer."

His novels in recent years have focused on elderly, ailing characters - from The Brooklyn Follies, which begins with the words, "I was looking for a quiet place to die", to those who mourn the accumulation of losses as loved ones die around them in The Book of Ilusions and Man in the Dark. Perhaps it is a preoccupation with his own mortality? He has struggled with ill health and was in a car crash a few years ago. But, now, at the age of 62, he appears robust, itching to produce as much as time will allow, with thoughts that are back on a youthful trajectory. Another book Sunset Park is already written and waiting to be published after Invisible. "I think my old man cycle is over. Invisible is about the innocence of youth."

Sunset Park appears to be so too, featuring four penniless twenty-somethings and situated in the post credit-crunch era of the here and now. "It is set in a down at heel neighbourhood in Brooklyn...They take over an abandoned house to become squatters."

The pause between books is never a pleasant state, he reflects. " Each time I think it's the end. Right now, I have no idea what to do next." With that, he melts back into Brooklyn's streets, the Sweet Melissa cipher with a Pied Piper trail of admirers never far behind.

Arifa Akbar travelled with Virgin Atlantic ( www.virginatlantic.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments