The Indy Book Club: Flowers for Algernon is a sad, sweet interrogation of what it is to be human

Our first pick in our new fortnightly book club is a 1959 sci-fi classic that asks readers to question all that can be lost with intelligence, writes Annie Lord

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At university, I had a lecturer who used to watch Strictly Come Dancing so that she had something she could talk to normal people about. She was so insanely clever, her brain so swollen with theories on phenomenology, existentialism, the categorical imperative, that she often struggled to communicate her thoughts to the rest of us.

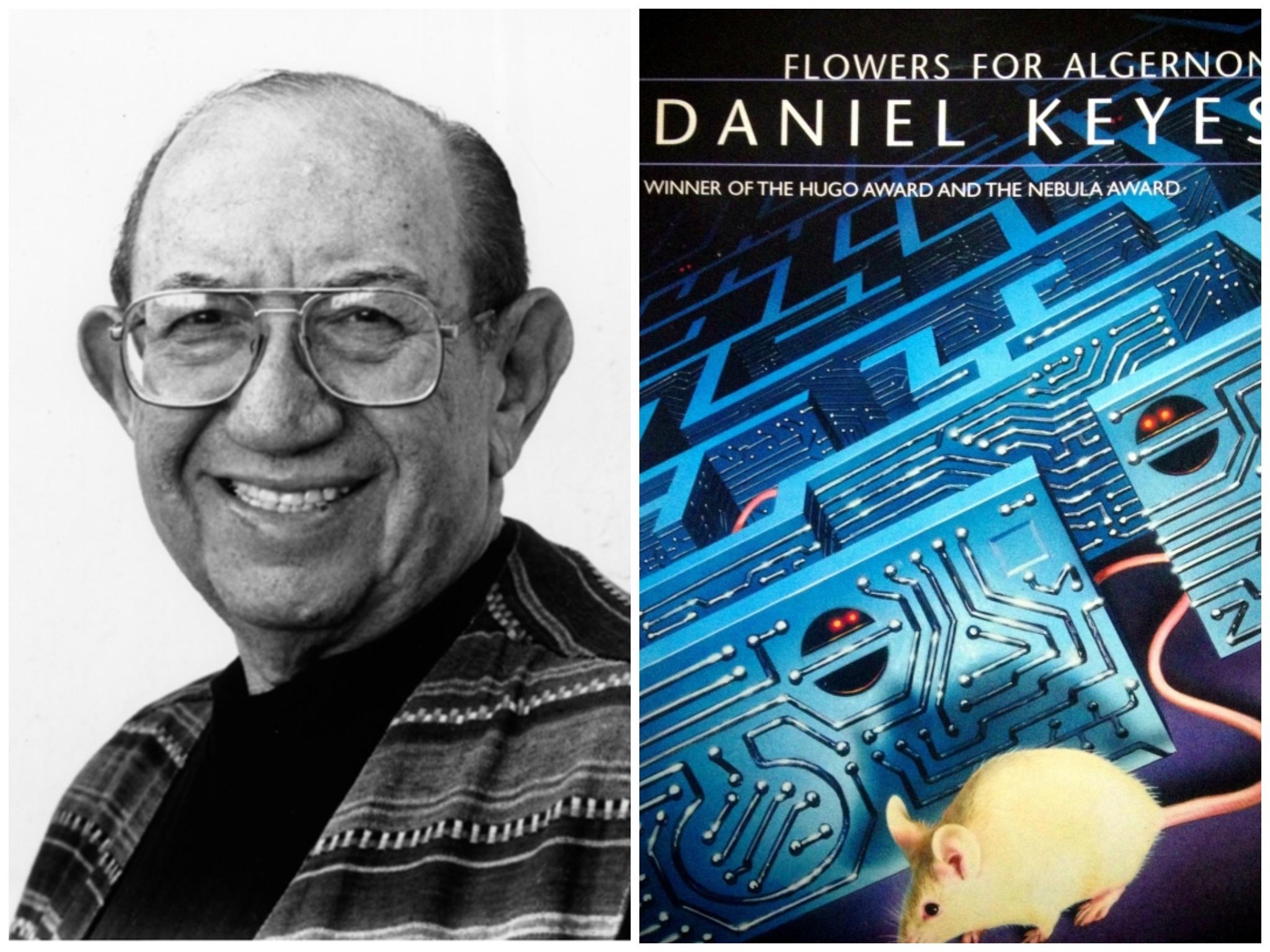

Often, the smarter you are, the more isolated you become from other people. This is one of the defining messages of Daniel Keyes’s Nebular Award-winning sci-fi classic Flowers for Algernon. Reading the novel made me think of how lonely it must have been for my lecturer when no one in the supermarket queue or the hairdressing waiting room could understand her.

The novel follows Charlie Gordon, a cleaner who has an IQ of 68, but who “reely wantd to lern I wantid it more even then pepul who are smarter even then me”. His life changes when the teacher of his nightly class for special needs adults recommends him to be the first human being to undergo an operation for artificial intelligence. While the scientists have already managed to carry out this experiment on a lab mouse called Algernon, as Charlie points out: “You know Charlie we are not shure how this experamint will werk on pepul because we onley tried it up to now on animils.”

It doesn’t take long for the experiment to take effect, and as Charlie’s IQ skyrockets to 184, he gains things: the love of a woman, relief from the bullying, the ability to decipher mathematical variance equivalent in Dorbermann’s Fifth Concerto and “review Vrostadt’s equations on Levels of Semantic Progression”. But he loses things as well. His trust in others, the bliss of ignorance, joy.

Charlie’s spelling and grammar, documented through a series of diary entries, improve as he begins to understand this world that has so often escaped him: “Punctuation, is? fun!” But his newfound eloquence soon falls away: “Please … please … don’t let me forget how to reed and rite.” These shifts in cognisance occur so subtly that at first you barely notice them; such is the care in Keyes’ writing. Charlie changes before you in ways so gradual you only notice in retrospect.

Having spent so much time reading the supposed ruminations of his inner feeling, I found myself caring so deeply for Charlie that I wanted to reach through the pages and hug him, tell him how special he was, how positively he marked the world even though he was not long in it. When Algernon passes away and Charlie asks: “please if you get a chanse put some flowrs on Algernons grave in the bak yard,” I couldn’t help but cry. Even after becoming aware of the unhappy fate that awaits him, Charlie couldn’t help but consider the fate of something else. That a mouse doesn’t feel alone when buried in the soil. That its grave be properly marked.

Towards the end of the novel, Charlie sees that intellectual superiority is not the sum total of a person’s worth. In one of his final progress reports, he tries to convey this message to Professor Nemur: “PS please tel prof Nemur not to be such a grouch when pepul laff at him and he would have more frends. Its easy to have frends if you let pepul laff at you. Im going to have lots of frends where I go.” Charlie can’t articulate himself very well anymore, but the message rings with the truth of his lived experience. Our humanity is not measured by how intelligent we are, but rather by the kindness we show in our interactions with others.

After finishing Flowers for Algernon, I realised that the most beautiful thing about my lecturer was not that she read lots of books, but that she watched reality TV just so that what she read in her books might better touch other people.

Here’s what some of our readers thought...

Brendon Hall

I found this an exceptionally moving story. Charlie’s slow realisation that his newfound intelligence and understanding of the human condition that slowly disappears made me think very hard about my grandma’s Alzheimer’s disease. I’ve never read anything that so convincingly depicts the slow and inexorable descent back into the dark black hole of the mind.

Hannah Kullar

This book hits you in the emotional jugular. As a kid, I struggled to fit in at school, so the passages where Charlie is being bullied I found particularly affecting.

Daniel Marsh

I first heard about Flowers for Algernon after watching The Simpsons episode “HOMR” which takes inspiration from the book. In it, Homer realises the root cause of his lacking intelligence: a crayon that was lodged in his brain from the age of six. He removes the crayon only to find that life doesn’t get any easier, it gets harder. Flowers for Algernon, and its more lighthearted cartoon adaptation, convey the message that intelligence is a gift, but one you often have to pay for. In perhaps my favourite quote of the novel, Charlie wonders: “I don’t know what’s worse: to not know what you are and be happy, or to become what you’ve always wanted to be, and feel alone.”

Sam Ramsey

What an exciting read! I sort of feel like it was too simple, but still an enjoyable enough book.

Miranda Whone

You can tell this book is from the Sixties (or just before) because it is so obsessed with cognitive psychology. Books from this era frustrate me. They are just so smugly assured of the whys and wherefores of human nature, as if it really were all that simple. It also is filled with unimaginative archetypes, there aren’t women but The Cruel Mother, The Virgin, The Whore. People love this book but I think it’s a waste of time.

Mark Briggs

Flowers for Algernon was almost too much for me. My brother Fred has a mental disability and reading this book reminded me of all the bad things I used to put him through when we were kids. It’s as though Flowers for Algernon were a mirror, and it showed me my shortcomings in the past that I had always avoided confronting. I hope that when people read it, they learn to treat people like Charlie with the compassion and kindness they deserve, because that’s all people need to survive the world we live in. I certainly learnt to appreciate that I’m the only thing Fred has in his life and I will work harder to keep him safe.

Our next Indy Book Club pick, as voted for by you, will be Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck. Send over your thoughts on the book to annie.lord@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments