Hugh Hefner created a magazine that was decades ahead of its time

Articles published in Playboy spanned a myriad of subjects including race issues, religion, sex and sexuality – many of which would not be covered by mainstream publications for several decades

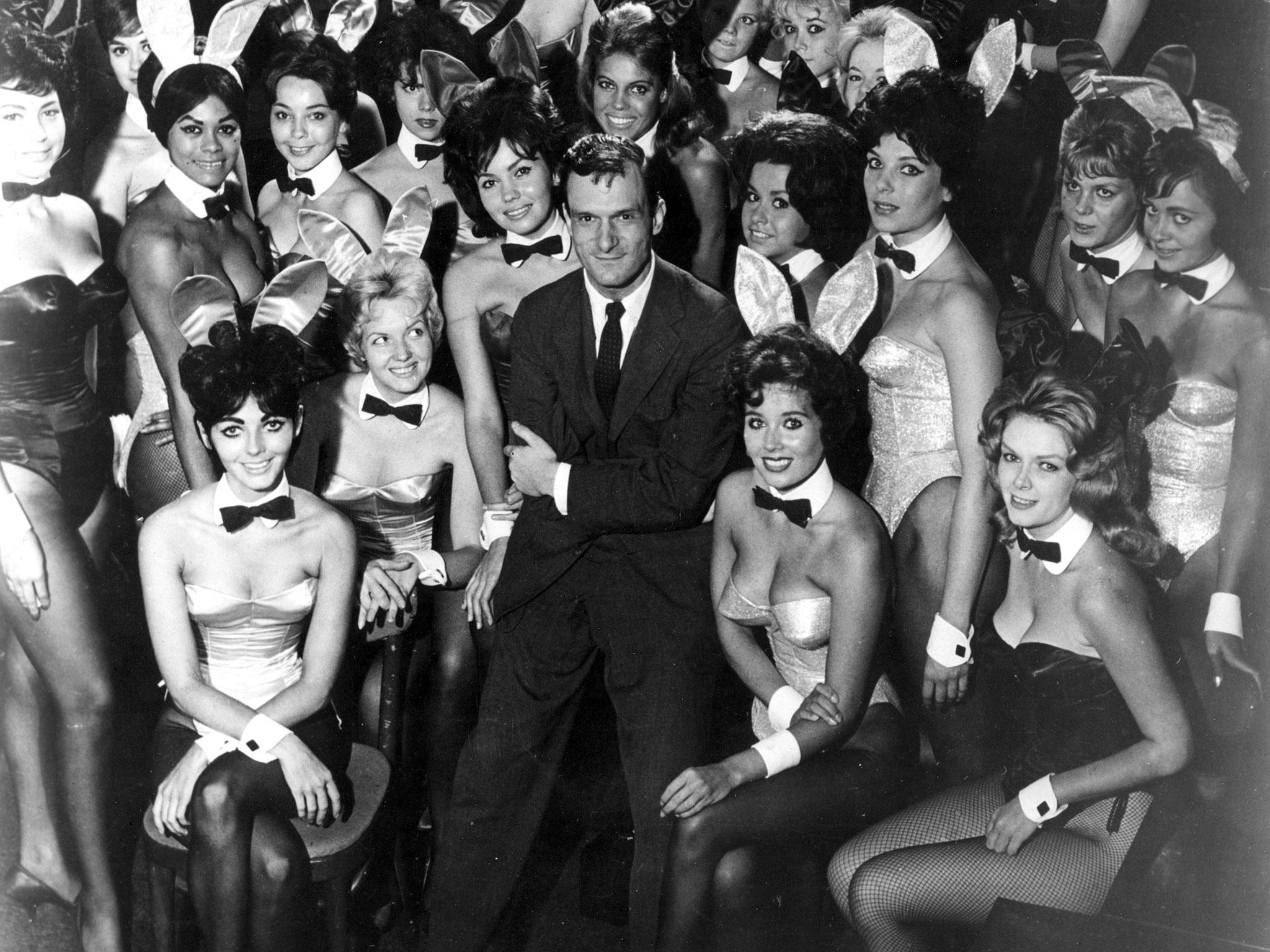

Playboy Magazine founder Hugh Hefner leaves behind a polarising personal legacy, reflective of the divisiveness of the man and the myth which surrounded him.

But beyond the tales of libertine excess, he should be revered as a magazine publishing pioneer that for decades would publish some of the most vital and groundbreaking articles of its time.

By publishing the first issue in 1953, with Hollywood’s most iconic and intriguing star Marilyn Monroe at its heart, Hefner would change the way middle America thought about sex – and art.

The running joke was that people caught in possession of an issue of the magazine were “reading it for the articles”, not for the naked images of women – however this was more often than not, the unlikely truth. Hefner himself once admitted to a group of former playmates: “Without you, I’d be the publisher of a literary magazine.”

Those who dismiss the magazine as sleaze and Hugh Hefner as nothing more than a pimp are either entirely ignorant or choosing to willfully ignore the thousands of critical essays, interviews, short stories and features published in Playboy under Hefner’s watchful eye. Articles spanned a myriad of subjects including race issues, religion, sex and sexuality – many of which would not be covered by mainstream publications until several decades later.

The very first Playboy interview published in the magazine was with Miles Davis, interviewed by black journalist Alex Haley. Hefner was a huge jazz fan, and would go onto launch and franchise entertainment venues which bore the Playboy logo. They hosted mixed-raced audiences and saw both black and white artists perform on stage. As he recalled to CBS in 2011 – if he discovered black club members were being refused entry, Hefner would reportedly buy back the franchised clubs.

In 1956, Hefner hired Playboy’s first literary editor, New York sophisticate Auguste Comte Spectorsky. As author James Gilbert wrote in his 2005 book Men in the Middle: Searching for Masculinity in the 1950s, it was Spectorsky’s job to “find the writers”. Hefner furnished “the lifestyle, the philosophy, and the girls”.

“Spectorsky surveyed the world of letters in the late 1950s and despaired at his discovery - or better - at what he could not find, which was a thriving, masculine high culture,” Gilbert wrote.

“[He] brought sophisticated cultural tastes and contacts with highbrow periodicals like the New Yorker to Hugh Hefner’s softcore pornography. To Hefner, this veneer of high culture was an essential marker of the sophisticated lifestyle that the Bunny enterprises promoted."

Once he was on board, Spectorsky went onto solicit fiction and non fiction from some of the most influential writers in the English-speaking world: Haruki Murakami, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Margaret Atwood, George Langelaan, Roald Dahl, Gore Vidal, Joyce Carol Oates and Truman Capote to name but a few.

Capote penned an article that detailed some of the most outrageous stories from the life of his friend, the playwright Tennessee Williams, and was the subject of a 1968 interview about subjects including his views on capital punishment, and the role of Jewish writers in the American literary scene.

In Vidal’s essay “Sex is Politics”, the writer and intellectual argued that politicians were using sexual issues as a controlling mechanism for society, using the ovcerarching, heteronormative patriarchy that governed the US political system to illustrate his point.

Margaret Atwood, who had written a number of books widely interpreted to have feminist messages, surprised readers when her byline appeared in Playboy in 1991. Her story The Bog Man, which was also published in the collection Wilderness Tips, told the tale of a woman who digs up a 2,000-year-old-man.

As well as publishing a number of his own short stories in Playboy, the late sci-fi icon Arthur C. Clarke was interviewed by the magazine in a 1986 profile piece which notably saw him admit to having a “bisexual experience”.

“If anyone had told me that he hadn’t, I’d have told him he was lying,” he added. His comments came over a decade after Hefner’s own admission that he had experimented sexually with men.

On the subject of sex – for all critics who would love to dismiss Playboy as a misogynistic den of iniquity – the magazine was as progressive as it was possible to be and have social impact.

In 1979 it published a survey on American men which aimed to challenge the stereotypical ideals of its own readers, by using males between the ages of 18 and 49 about subjects including basic values, love, family and sex.

“Most men are hardly playboys in their values and attitudes,” the survey determined. “Nearly 85 per cent rated family life as very important for a satisfied life, while only 49 per cent rated sex as similarly important.

“Married men had the highest levels of satisfaction with their sex lives, and three out of four men considered sexual fidelity very important for a successful marriage.”

It presented these findings in a way that did not judge; rather it pointed out a link between a healthy sex life and fidelity in marriage – something which must have been surprising to many considering the publication was run by a man perpetually garbed in a dressing gown and surrounded by women.

As well as its open and frank discussion over the sexuality of its writers and its founder, Playboy was also an early advocate for gay rights and projected the discussion of homosexuality into the mainstream.

The Crooked Man, a sci-fi short story by Charles Beaumont, pondered a world in which homosexuality was the norm and heterosexuals were persecuted.

He told The Daily Beast in one inteview: “Without question, love in its various permutations is what we need more of in this world.

The thrice-married Henfer added: “The idea that the concept of marriage will be sullied by same-sex marriage is ridiculous. Heterosexuals haven’t been doing that well at it on their own.”

A dedicated champion of the arts, Hefner helped to organise funding efforts in 1978 which led to the restoration of the then-dilapidated Hollywood Sign, hosting a gala fundraiser at the Playboy Mansion and personally contribution 1/9th of the total restoration costs by purchasing the letter “Y”.

In 2005, Amy Grace Lloyd was hired to revive Playboy’s literary tradition. In a piece for Salon published in 2013 she recounted the hostile reaction she received when her role was revealed at a dinner party by people who accused her of being anti-feminist, a sellout to womenkind.

Yet she said of working there: “I expected some sexism, a run-in or two with sexual harassment, but I was disappointed in this, happily. Certainly, sex was in the air, the stuff of endless humour, of puns, double entendres. You had to be light on your feet.”

She went on to write how working at Playboy taught her to say ‘no’, or “to choose my yes’s and no’s with some care”.

“No, I’m not less of a feminist because I worked at Playboy,” she wrote. “I included women’s work in the magazine at every possible occasion. By working at Playboy I’m not seducing any woman out of her clothes (though I must admit that sounds appealing).”

She stated, correctly, how Playboy was a magazine that Americans loved to deride but couldn’t help but be fascinated by, drawn into. And that was the power of the magazine. It celebrated sex, and art - and was never ashamed to say it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks