How crime fiction has moved on

An exhibition at the British Library explores the A-Z of the classic whodunit

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At the entrance to the Murder in the Library, a compact new exhibition that charts the A-Z of crime fiction at the British Library, there's a panel that lists Monsignor Ronald Knox's 10 rules of detective fiction, which are as follows:

1) The criminal must be someone mentioned in the early part of the story, but must not be anyone whose thoughts the reader has been allowed to follow;

2) All supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course;

3) Not more than one secret room or passage is allowed;

4) No hitherto undiscovered poisons may be used, nor any appliance which will need a long scientific explanation at the end;

5) No Chinaman must figure in the story;

6) No accident must ever help the detective, nor must he ever have an unaccountable intuition which proves to be right;

7) The detective must not himself commit the crime;

8) The detective must not light on any clues which are not instantly produced for the inspection of the reader;

9) The stupid friend of the detective, the Watson, must not conceal any thoughts which pass through his mind; his intelligence must be slightly, but very slightly, below that of the average reader;

10) Twin brothers, and doubles generally, must not appear unless we have been duly prepared for them.

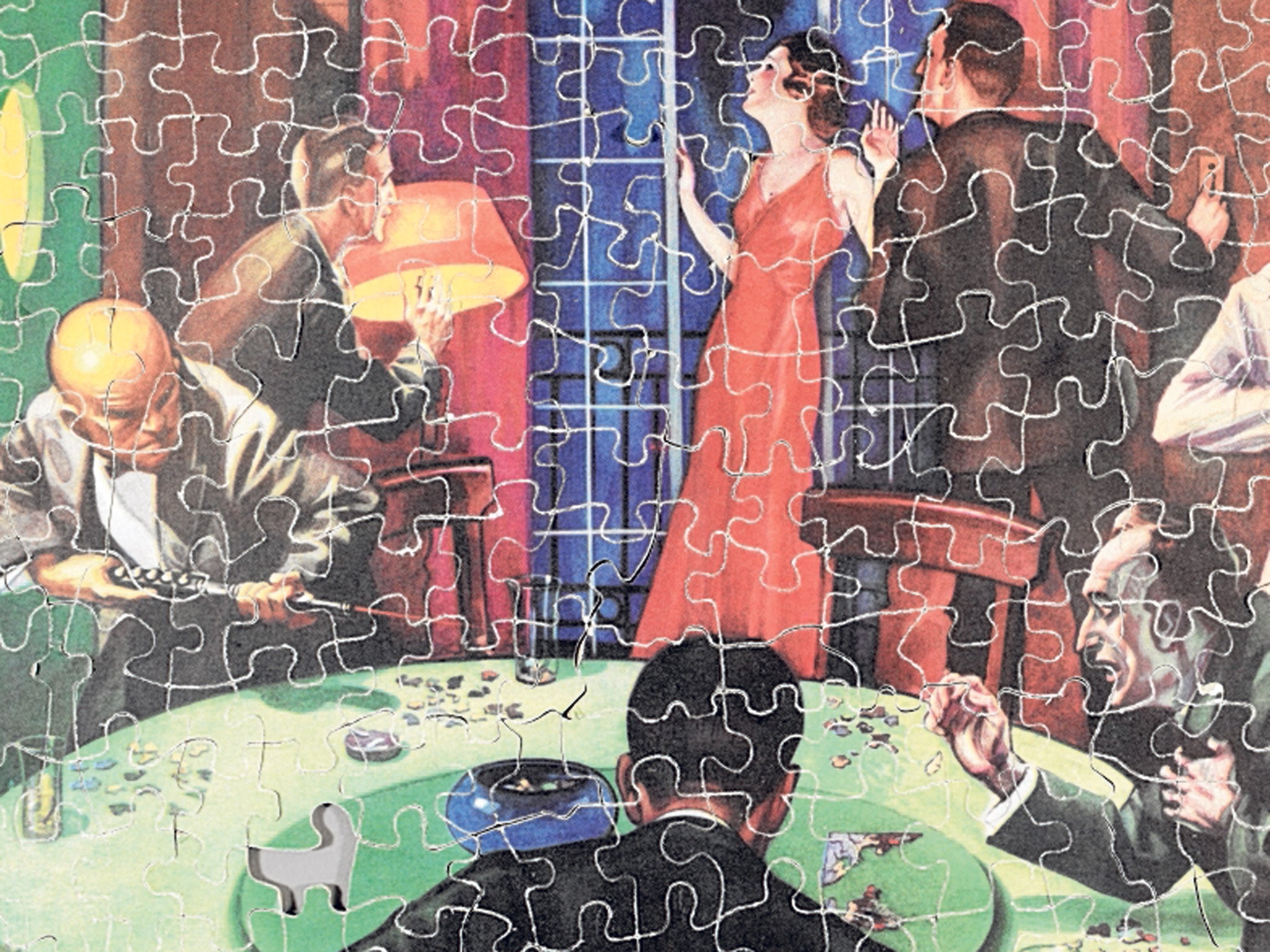

Knox came up with these commandments as a preface to Best Detective Stories of 1928-29 (hence the murderously un-PC "Chinaman" comment), so he was writing about the Golden Age of detective stories. This era is represented in Murder in the Library by examples of the work of Agatha Christie, of course, Dorothy L Sayers and Ngaio Marsh, as well as exhibits of less well-known whodunits that variously reveal the identity of the killer via a jigsaw (The Jigsaw Puzzle Murder by Walter Eberhardt, 1933), or let readers work out the culprit by studying real clues (cigarette ends and hair clippings in the case of Murder Off Miami, by Dennis Wheatley and JG Links, 1936) that come neatly packaged for that purpose. Whodunit was both the genre, and what every reader wanted to try and work out. It was about reading, but also about solving a puzzle.

But more than 80 years after the Golden Age's prime, does the whodunit have a place in modern crime fiction, or has it been bumped off by serial killers, scalpel-wielding pathologists and sophisticated cynicism? And are readers even given the chance to be have-a-go heroes anymore? "I always try and work out whodunit, but I'm very bad at it," confesses Kathryn Johnson, curator of theatrical manuscripts at the British Library who put together the exhibition. "Ronald Knox's rules are a bit like the rules of cricket, it's an intellectual game, and the author/s and the readers were sort of in a pact: if the authors played fair, then the audience would carry on buying their books." The puzzle, she explains, was the pleasure. "In the 1920s and 30s the prevalent form of detective fiction was the puzzle, which was presented almost like an intellectual exercise. It's no accident that the heyday of the puzzle mystery was at the same time as crosswords became extremely popular."

But modern writers don't play by the rules now. "I spent two whole weeks reading Foucault's Pendulum, which I know is a work of great scholarly rigor, but there is a murder – and you don't find out who the murder is. I was furious. I think you do still expect to have your questions answered." She thinks the whodunit has evolved. "It's became a whydunit or a howdunit."

Stav Sherez, author of, most recently, A Dark Redemption and whose work has been shortlisted for the CWA John Creasey Dagger, likes to play fair with his readers. "I very rarely know who the killer is until a later draft but then I will reverse engineer the text to make sure the clues are there and if one re-reads the book then I think it should be obvious. It's too easy to cheat and much harder, more demanding and challenging, to pepper clues throughout the text but hide them within a sprawl of other clues and dead ends." Is there a place for the classic whodunit, with its set cast of characters and specific locale (country house, hotel) today? "That can work very well in modern fiction as it is an essential puzzle that drives us through the text. It also creates a nice claustrophobic atmosphere and makes you suspect every character that appears. But, unlike in the past, it has to be counter-balanced by psychology and good prose."

What about when reading mysteries is your job? Reviewer and crime-fiction expert Barry Forshaw, author of, among other blood-soaked titles, Death in a Cold Climate: A Guide to Scandinavian Crime Fiction and The Rough Guide to Crime Fiction laments the fact that he can usually spot a murderer a mile off. "I really love the ones that do defeat me." He thinks the traditional whodunit is dead, but that in the right hands, some of its traditions have been carried on. "The classic example is PD James. She likes Sayers (they all do – Ruth Rendell, Minette Walters) who has more psychological depth, but when PD James has done things in the style of, or homages to, the Golden Age, she can't just do the puzzle anymore because readers now want psychology."

The final word goes to Baroness James of Holland Park herself. In her elegant 2009 work Talking about Detective Fiction, she writes that "the solving of the mystery is still at the heart of a detective story," but that, like all forms of entertainment, it has, as it must, evolved. "I see the detective story becoming more firmly rooted in the realities and the uncertainties of the 21st century, while still providing that central certainty that even the most intractable problems will in the end be subject to reason." Fewer secret rooms, then, and a lot more psychology are the hallmarks of the modern whodunit.

Murder in the Library: An A-Z of Crime Fiction, in association with the Folio Society, runs until 12 May. For more information and to book forthcoming exhibition events (such as The Female Detective, Fri 8 Mar, 6.30-8pm) go to bl.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments