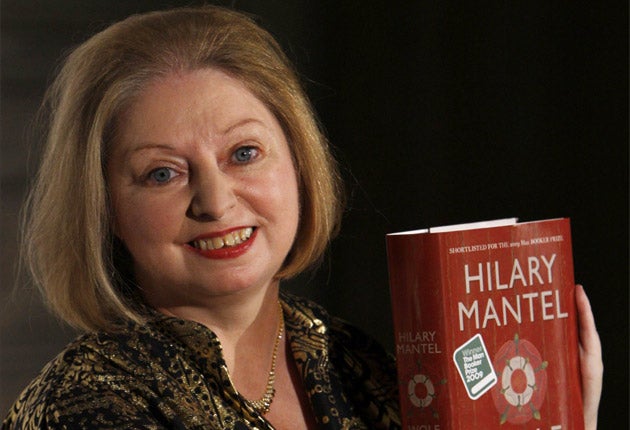

Hilary Mantel: Her grasp on character and circumstance was equal to Shakespeare

The literary world is reeling from the death of twice-Booker Prize winner Hilary Mantel, at the age of 70. Claire Allfree remembers a writer of seismic impact

In 2017 Hilary Mantel opened her first of five Reith lectures by quoting St Augustine. “St Augustine says the dead are invisible, they are not absent,” she said, and then added, “You needn’t believe in ghosts to see that that’s true”. I am not sure if Mantel herself believed in actual ghosts – one can scarcely imagine her cowering at the foot of a bed in terror in the middle of the night, although she was brought up Catholic – but she undeniably believed in the power of history to manifest itself as a sort of psychological haunting. Certainly, no writer better depicted the past as though it were a continuous shapeshifting present than she did in her groundbreaking Wolf Hall trilogy. Her magnificent telling of the story of Henry VIII from behind the eyes of his inscrutable right-hand man Thomas Cromwell made her the first – and still only – woman to twice win the Booker Prize. It also made a generation of readers feel they were right inside Cromwell’s head with him.

The literary world is reeling from the sudden, shocking death of Mantel, and rightly so. I can’t think of many authors who have delivered sentence after sentence of complex pleasure while simultaneously producing chapter after chapter of heart-racing action the way she did in the Wolf Hall trilogy. She regarded those three novels, which took her 15 gruelling years to write, as her life’s work. Like many of her previous neglected works of fiction, they exemplified her belief in history as best understood not as a series of facts or even events but as a subjective sequence of hallucinatory, almost subconscious experience. Ghosts are everywhere for Cromwell in these three novels – be it his father beating his childhood self to a pulp on the streets of Putney; Anne Boleyn, whose execution he engineered, picking up her head and chasing him through the corridors of Whitehall; or the recent past itself, in the form of an unquiet spectre forever pressing down on him. Throughout he is haunted, also, by the prospect of his own untimely death at the hands of a volatile and capricious king. We know it is only a matter of time. He does, too.

Yet at the same time, Mantel had the great novelist’s knack of making dusty, distant events snap exhilaratingly to life. That’s a cliche – all historical novelists do, or should do this – but Mantel had a grasp on character and circumstance, and their relationship to the ever unpredictable narrative of fate and power, to equal that of Shakespeare. In her almost gleeful, impeccably researched exploration of the machinations of the Tudor Court, she summoned the fabulously monstrous paranoid appetites of Henry and the dark arts of Cromwell, a 16th-century Dominic Cummings in ermine and silk. In doing so, she reflected back at us not only our founding national myth but the fragility, precariousness and strength of our modern political system. No wonder we couldn’t get enough. Politics as a snake pit of ego, paranoia, hubris and outstanding ambition: who could not see the 21st-century Westminster suits behind the Tudor doublet and hose?

Mantel herself was haunted throughout her life. In her memoir Giving Up the Ghost, she writes about seeing her stepfather Jack in the house of her late mother. Jack died in 1995, but Mantel had seen him several times since – or, perhaps, she then wonders, the sighting was merely a warning of an imminent migraine attack. “I don’t know whether, at such vulnerable times, I see more than is there or if things are there, that I don’t normally see,” she wrote. She was haunted, and to some extent shaped, by the ill health that dogged her mind and body since her teens – at the age of 27, after years of undiagnosed, excruciating pain (she suffered savagely from endometriosis), she had her ovaries removed. She writes angrily and pitilessly of having to confront the fact she would never have children; it’s hard to imagine that her sorrow over her childlessness ever left her. Yet in person she was gracious, beady, with a light sing-song voice and a slightly terrifying intelligence. I met her once around the publication of The Mirror and the Light, in a flat she owned in greater London with her husband Gerald, and which was decorated somewhat surprisingly in soft pinks and flouncy curtains. It was one of the most rewarding and enjoyable conversations I think I’ve ever had.

For while her body sometimes let her down, Mantel remained an unfailingly robust, sparkling and always absolutely stimulating commentator on national life. She was a terrific essayist, although it’s ironic she is probably best remembered for the one that caused enormous controversy when in 2013 she described the Duchess of Cambridge as a “shop window mannequin” in the London Review of Books. (What became instantly clear was that most of those piling in had almost certainly not read the original essay, since its real target was a modern monarchical system that reduced its female players to puppets.)

She understood the nuances of history, power and politics better than many an academic historian. And she wrote several stylistically various novels before Wolf Hall, from Eight Months on Ghazzah Street (1988), which drew with characteristic perspicacity on her expat experiences in Saudi Arabia, to 2005’s excellent Orange Prize-nominated Beyond Black, which, in its portrait of an alarmingly damaged psychic, explored her keen interest in the link between psychological experience and the supernatural.

Yet it’s Wolf Hall that will define her and for which she will always be remembered. Yes, the TV adaptation starring Mark Rylance was excellent; yes, the RSC adaptations, the final instalment of which she co-wrote herself, were great. But it’s the novels that matter. The concluding paragraphs of The Mirror and The Light, in which Cromwell walks towards the executioner sent shivers down my spine when I first read them. They send shivers down my spine again now. “He feels for an opening, blinded, looking for a door: tracking the light along the wall.” It was her final sentence. What a writer she was.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks