Hank Green: ‘It’s vital that we be critical of the things we love’

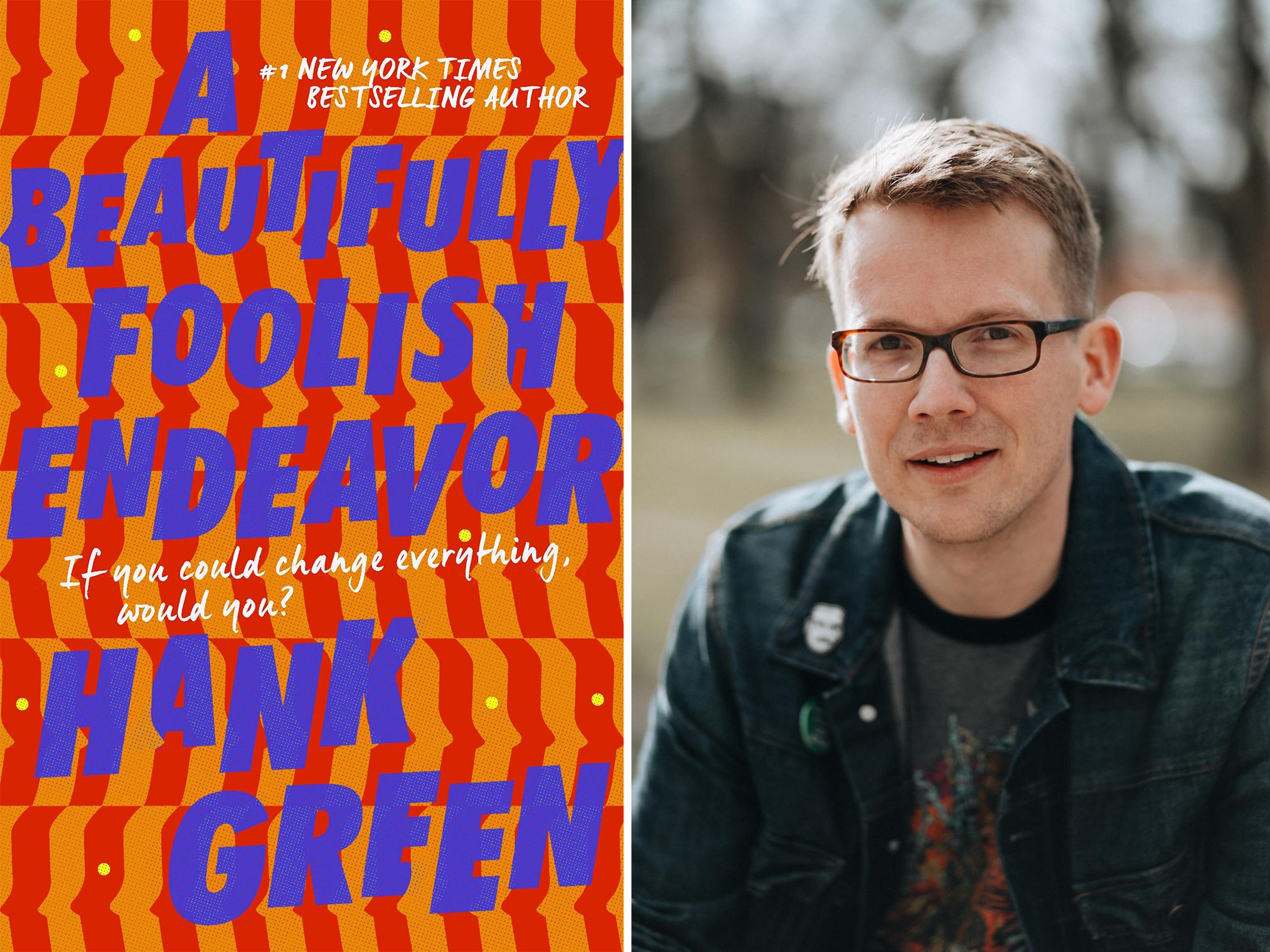

The YouTuber, entrepreneur, and author – among other job titles – recently published his second book, ‘A Beautifully Foolish Endeavor’. He talks to Clémence Michallon about online life, fear-mongering, and why he remains ‘hopeful about the future of humanity’

Hank Green is a busy man. So busy, in fact, that there exists a website solely dedicated to counting the days since he started a new project. At the time of our interview, the counter stands at 15 – the number of days that have elapsed since Green created a newsletter about “creation, media, money, community, education, and power”. Two days later, it resets. Green is working on a “book of good times”, a prompt journal for those looking to live a connected, mindful, grateful existence.

You might know Green, 40, from the 13-year-old, ongoing YouTube channel Vlogbrothers, which he shares with his brother John. (Yes, The Fault In Our Stars author John Green – more on that later). You might know him from one of the many other online projects he has got involved in over the past decade, from the educational channel Crash Course to The Lizzie Bennett Diaries, a 2012 adaptation of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice in vlog form. You might have heard of SciShow and Eons and How To Adult and Holy F****** Science, which tackle various themes but all aim to share knowledge online for free.

Or you might know Green through his 2018 New York Times Bestselling novel An Absolutely Remarkable Thing, in which 23-year-old April May becomes the first person to encounter a form of alien life on Earth. April shares the experience in an online video, which catapults her into viral celebrity. The sequel (and final tome to what Green has insisted will remain a two-part series in a world of trilogies), A Beautifully Foolish Endeavor, was released earlier this month and also became a New York Times Bestseller.

While An Absolutely Remarkable Thing was a personal narrative, centred around April’s experience of online fame, A Beautifully Foolish Endeavor expands the story’s scope to take a broader look at how we think and behave on the internet – and, consequently, in real life. Both books share concerns that regularly surface in Green’s videos: how to be a person in the world, how collaboration (particularly online) can help us, but also how existing on the internet can hurt us on both individual and societal levels.

“I got to be more explicit [in the sequel] about the fact that I don’t think hate comes from a lack of access to information – or that hate would be solved by access to more information, because I think people choose what information they seek out and engage with,” Green says in a phone interview from his home in Montana.

“We are the ones who are deciding not just what we look at, but what gets made. So when we engage with stuff that’s fear-mongering, it encourages the creation of more fear-mongering. Whose fault is this? In many ways, it’s all of our faults. And when we complain about the media, what we’re complaining about is our own consumption behaviour.”

The online community fostered by the Green brothers, better known as Nerdfighteria, is one of the more wholesome corners of the internet. It is in many ways the product of a largely bygone online era, when social media was still infused with a sense of joy and creativity rather than existential dread. (For reference, recent Vlogbrothers videos tend to average between 100,000 and 200,000 views. A census of the community conducted by Green – because of course – returned around 41,000 answers and showed that Nerdfighteria is primarily female, US-based, and white. Oh, and they’re divided on whether buttocks are part of the legs or constitute a different section of the human anatomy – an age-old Nerdfighteria conundrum.)

On the phone, Green is talkative and thoughtful, candid but nuanced. He misses the “simplicity” of those earlier years, is frank about the “destructive” aspects of social media, including its potential for divisiveness. This is a refreshingly honest admission from someone whose career has been defined by the internet since before the 2010s.

“I don’t mean it to be just an indictment,” he says. “I mean it to be a criticism. I think it’s vital that we be critical of the things that we love.”

Our interview is taking place at a turbulent time for YouTube, with several high-profile creators having taken a break from the platform or left it for good. Some chose to step away, others have been silent in the wake of various reckonings. When Jenna Marbles, a legacy YouTuber, announced in June that she was leaving the video sharing website over past offensive videos, Green tweeted in part: “I really strongly believe that we should be judged not by how we acted when we were ignorant, but how we responded when we were informed. By that measure, Jenna Marbles is head and shoulders beyond a great many YouTubers.”

Green’s own social media presence is – like much of his other work – a mix of humour, musings, information, and, occasionally, commentary on more serious issues. Some of his recent tweets have tackled themes such as college education in the US, how fascists concentrate power, and class conflict. While his brother John stepped away from Twitter in December 2018, Hank Green, who has more than 800,000 followers on the platform, is still engaging in precisely the type of online discourse that can easily lead to some maddening, off-putting exchanges.

So why does he do it? Well, mainly, he believes that being part of the conversation, however imperfectly, is better than staying silent. “I feel like doing nothing is probably worse than trying to engage with a problem, trying to get good ideas out there, trying to help people understand where we’re at,” he says. “...I feel occasionally that I have an obligation when I see things that are very clearly about consolidating power and one room in Washington, rather than sharing power in the way that was very intentionally set up.”

Beyond his – sizeable – corner of the internet, Green is a husband and a father to a three-year-old son. He is also – it is a rule universally acknowledged that every Hank Green profile must mention this – his brother’s brother, a fact he was reminded of with increased frequency following the release of his first book. John Green’s fourth solo novel, the 2014 The Fault In Our Stars, was a once-in-a-generation phenomenon. It seems natural, if a bit on the nose, to wonder how his younger brother felt when it was his turn to enter the literary field.

“I have never thought to compare my novels to John’s novels,” he says with sincerity. “People bring it up all the time and it sounds like gobbledygook. It doesn’t compute with my brain. Why would I compare [our respective books]? One, they’re very different kinds of books. Two, [John] is very good, and I don’t expect myself to be either good at the same thing he’s good at, or as successful as that, because that doesn’t make any sense at all.”

Not only that, but having witnessed success of that scope up close, Green isn’t sure he’d like to experience it. “It’s really intense and hard. I think that we rightly spend more time thinking about and criticising the stuff that is really successful, because we want to make sure that we understand all the ways that it is both a positive and negative influence. It isn’t always a bad thing. Sometimes it’s right that we spend more time focusing on the successful stuff. And so I don’t really want that level of scrutiny on my work. It sounds really intimidating.”

For all its reflections on social media and the anxieties of internet fame, A Beautifully Foolish Endeavor has been deemed a hopeful book. In Green’s fiction, much like in his online content, criticism isn’t viewed as an admission of failure, but rather as a possible path towards a better world.

“I am hopeful about the future of humanity. I think that we are really remarkable, team-building, problem-solving machines. … What I don’t have hope for is that we fix anything without recognising the problems and identifying them correctly. You cannot solve a problem if you do not correctly identify what it is. I worry about that. It’s a meta problem where we have these new tools that are interfering with our ability to correctly identify what the problems are. So that itself becomes a big problem that we have not so far been great at figuring out how to solve.”

A Beautifully Foolish Endeavor is out in the UK (Trapeze) and in the US (Dutton).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks