All Boys Aren’t Blue author George M Johnson: ‘You’re conditioned to think a 12-year-old isn’t ready for these topics’

The activist and writer talks to Nicole Vassell about their startling memoir of growing up Black and queer in New Jersey, its frank discussion of sex and trauma, and about weighing up personal vulnerability against how it would feel ‘if I kept something back, and have to watch someone be harmed because I said nothing’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I was five years old when my teeth got kicked out. It was my first trauma.”

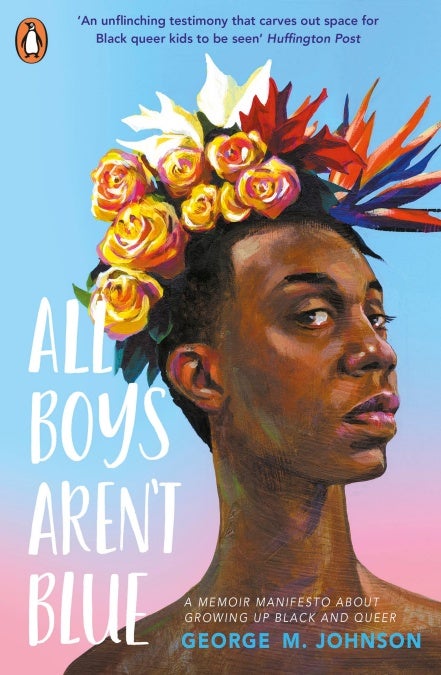

So begins a series of jarring, vivid scenes expressed in George M Johnson’s memoir All Boys Aren’t Blue, a courageous telling of their life growing up as a Black, queer boy in late Nineties and early 2000s New Jersey.

Inspired by the late Toni Morrison’s quote on the need to write the book you want to read, Johnson writes for the young, queer person they were. They see it as the book they wish had existed as they made their way through a world that never wanted to see them fully.

Johnson has used they/them pronouns since 2019: “My body is just my physical shell, it doesn’t dictate who I am inside; if I didn’t have to use pronouns at all, I wouldn’t,” they shrug over Zoom from Newark, New Jersey, before taking a hearty sip from a heat-insulating mug. They’re dressed in a dark, neutral jumper and knitted hat.

Yet Johnson’s disillusionment with the gender binary has been lifelong, and is represented in the book’s title: one meaning of the “blue” in it represents the rejection of “boy”. Plus, this feeling is apparent to readers early on: their child self occasionally has daydreams of growing up to be a buxom beauty named Dominique.

Readers are let into plenty of other key moments from the first 35 years of their life, from realising that they would be saved from being a playground pariah if they traded in skipping with the girls for American football with the boys to learning some tough truths about how Black people in America have been treated throughout history; from establishing their first meaningful connection with another queer person in the form of cousin Hope, a gregarious trans woman to a devastating loss as a final-year university student that changes their life.

With splashes of humour and richly expressed declarations of love for their family, who’ve defended Johnson fiercely and often, All Boys Aren’t Blue balances out the harsher experiences with warmth and the belief in a future that everyone must contribute to making better.

“I think this story is important because it allows a lot of healing; a lot of freedom for the Black queer child and teen who even now still feel very suppressed and oppressed within wider society – and within the Black community,” Johnson says.

“Black queer memoirs have existed before mine, but a lot of them exist in the adult space. We never really get to tell our story and make sure it gets directly to the next generation of people who will live our experience.”

As a writer and activist on LGBTQ+, racial justice and gender issues, with a significant platform, Johnson was likely to write a book at some stage of their career. But the catalyst to start telling their story came during an onslaught of violence against queer young people of colour reported in the late 2010s: Johnson remembers the story of gay 14-year-old Giovanni Melton, whose father is currently awaiting trial for shooting him dead; Gabriel Fernandez, an eight-year-old whose death at the hands of his parents was the subject of a 2020 Netflix documentary; and Gemmel Moore, 26, a Black gay sex worker who was found dead in the apartment of California politician Ed Buck in 2017 – a second, Timothy Michael Dean, would be found dead in the same apartment in 2019.

Across the US, queer people of colour were violently dying, and the outrage felt limited due to their marginalised positions in society. For Johnson, there was no more crucial moment to contribute something useful to the narrative.

“I thought, if I don’t get this text into the hands of not just the kids, but the parents, the teachers, the owners of the barbershop, the preachers of the Black church – if I cannot tell this story, we’re about to be in a really bad place, community-wise.”

“It was time to really do the work; to get the story out there and to the people who really needed it the most – the children.”

Their point was soon proved; people were craving this story, whether they knew it before reading, or not. In the months since the US release of All Boys Aren’t Blue last summer, reviews have been nothing short of glowing, from critics and readers, children and adults alike. Johnson speaks fondly of receiving emails across age ranges declaring the book as the first time they’ve truly seen themselves in media, with the furthest source of praise coming from an octogenarian in Germany.

Actor and producer Gabrielle Union, who has a trans step-daughter, was so moved by the book that she optioned it for television as part of her first-look deal with Sony Pictures TV; she and Johnson are currently developing the memoir into a series. As exciting as it is to see their words on the verge of hitting the screens, Johnson never had a doubt about how far All Boys Aren’t Blue was going to end up; the more eyes on it, the better.

“I got advice on how to write the book to translate best for TV – that deeper level of depiction was always the goal.”

But in creating a piece of such resonance, Johnson had to access some dark, intimate truths and lay them bare for the world.

A central chapter of the memoir details the sexual abuse that they experienced around age 13 at the hands of their older male cousin. Without glossing over what was happening or zooming out of the scene, Johnson details the physical and mental confusion they felt in the moment, the shame and secrecy that followed immediately and years to come, and the way the event stayed unspoken until the time they started to write.

“Every person who reads this book will know more about me than I will ever know about them, and that’s a level of vulnerability that I don’t think a lot of people realise happens when you do this type of work,” Johnson explains.

Yet, they strongly believed that the feeling of discomfort in this exposure was worth the payoff.

“I realised that the more I hold back, the more harm happens to the next generation who needs this information. Which weighs more: the weight of me having to be a little more vulnerable or the weight that I’d feel if I kept something back, and have to watch someone be harmed because I said nothing?”

So, Johnson is candid – with the painful experiences, the euphoric ones, and the confusing spaces where they overlap. A late chapter called “Losing My Virginity Twice” contains a recounting of their first consensual sexual encounters while at university – both giving and receiving anal sex, with varying results. Though aimed towards a younger reader than most self-narratives, Johnson didn’t see this as cause to be coy or metaphoric – instead, now is the time to be the most real.

“Young adult doesn’t mean you can’t have adult conversations,” they reason. “What it really means is that you have to be willing to go to that place of breaking the conditioning that makes you think that a 12-year-old is not ready for these topics.

“I was fully vulnerable because trial and error is dangerous, especially for Black queer kids because of the HIV epidemic still being an epidemic in the Black LGBTQ+ community. They actually need those resources much younger so that they can be safe in the moment, as well as lowering the risk of longer-term implications.”

It’s clear Johnson sees the documenting of their story as a responsibility; a resource that’ll provide a roadmap for young queer people, while showing all who read that supportive, loving familial relationships between queer and heterosexual people can thrive – especially in Black communities. The focus on the positive connections they have with their biological brothers and relatives, as well as their “brothers” from their fraternity – a social organisation established at university – is strong throughout, and dispels grim assumptions of toxic masculinity.

Though homophobia is often a reality for queer people in domestic settings, All Boys Aren’t Blue is proof that it’s not always the case, and that it never needs to be.

With their second memoir already in the works, George M Johnson’s story is far from finished – and with the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter protests of last summer, and increased awareness of trans and non-binary gender identities in the media, their voice has the power to reach more people than ever.

It’s heavy work, but Johnson finds reasons to smile regardless.

“As Black people, it’s a lot to always be given the short end of the stick, every single time. A new pandemic hits, and we’re in the smallest percentile of those getting vaccinated and in the highest percentile of people dying. Every time something happens, it affects us so much worse.

“But in many ways, what makes me smile is always how we find a way to continue to love on each other, and show up for each other.”

With this memoir, Johnson definitely shows up.

‘All Boys Aren’t Blue’ by George M Johnson is published by Penguin, available now for £8.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments