Fu Manchu and China: Was the 'yellow peril incarnate' really appallingly racist?

Forget the warmth of the state visit: for decades, our attitude to China was defined by the portrayal of Fu Manchu. And, says Phil Baker, there was more to this fiendish figure than meets the eye

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

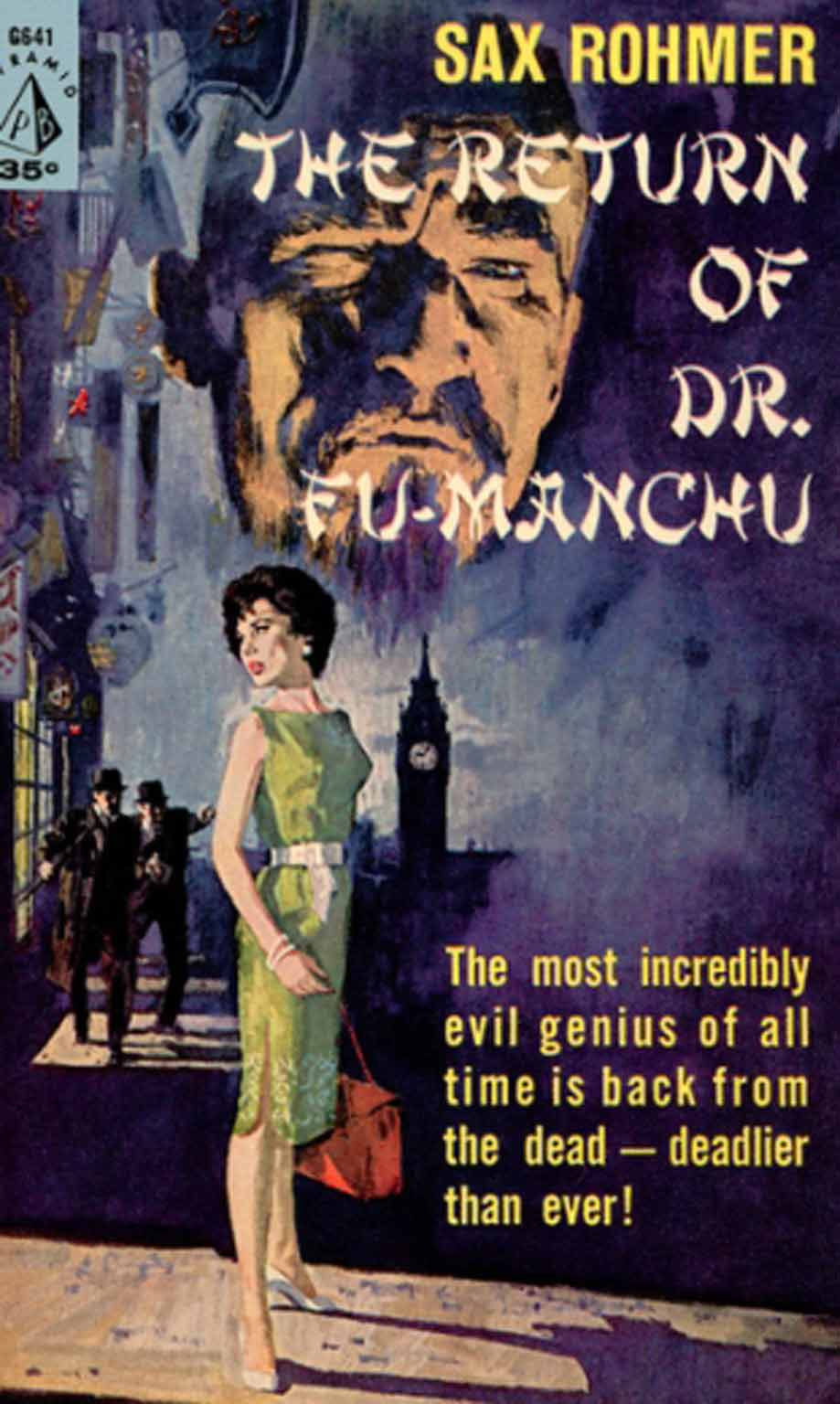

Your support makes all the difference.Sax Rohmer falls into the category – like HP Lovecraft – of truly great bad writers, and like Lovecraft he has only recently enjoyed a revival and re-evaluation. It was just over a century ago that Rohmer created the fiendish Dr Fu Manchu, “the yellow peril incarnate in one man”, hell-bent on nothing less than the downfall of Western civilisation. Supposedly the most evil man in the world, Fu Manchu was nevertheless much loved by his public, and by mid-century he had taken up residence in the same glorious realm as Dracula and Sherlock Holmes. Along with a series of novels, Fu Manchu generated endless spin-offs including five movies, a radio serial and even a brand of sticky sweets, as late as the 1970s, called Fu Man Chews.

His creator was born into the south London suburbs in 1883 as plain Arthur Ward, later adopting the middle name Sarsfield in honour of Irish nobleman Patrick Sarsfield, whom he claimed as an ancestor on his mother's side (which, if true, would make him a distant relative of Lord Lucan). He scratched a living as a writer for the music halls and collaborated with the comedian Little Tich, but his luck changed when – at least by his own account – he asked an ouija board how he could make his fortune and it spelled out the word C-H-I-N-A-M-A-N. This was despite the fact that Rohmer knew almost nothing about China, but getting the details right has rarely been a feature of the West's depiction of other cultures: when Boris Karloff appeared as the fiendish Doctor in the 1930 movie, Mask of Fu Manchu, he was regally togged-up in what was actually a high-class Chinese woman's wedding dress. What Rohmer did know about were the clichés of fin-de-siècle Yellow Peril hysteria, and the fantasy of London's Limehouse as a nest of criminality and opium smoking (although in reality it became considerably more law-abiding, not less, after the Chinese settled there, and a writer in The Times could observe that there was probably more degradation in the average British pub than the entire two streets of Chinese Limehouse).

Dickens' 1870 novel The Mystery of Edwin Drood has a lot to answer for here, with its depiction of a squalid opium den, but the Chinaphobia of the day emanated particularly from North America, where anxieties about ethnic minorities fuelled anti-drug hysteria in ways that we're still paying for with the War on Drugs. Chinese laundries were allegedly full of kidnapped American children, “tiny lost souls”, who were forced (at least in the fevered dreams of American labour leader and demagogue Samuel Gompers) to “yield up their virgin bodies to their maniacal yellow captors” – and as if that wasn't bad enough: “What other crimes are committed in these dark fetid places when these little innocent victims of the Chinaman's wiles are under the influence of the drug opium is too horrible to imagine.”

With this Yellow Peril background, it is not surprising that for some years Rohmer has been largely remembered, if at all, for appalling racism and his depictions of Chinese cruelty – certainly not topics that would have been deemed suitable for discussion at last night's royal banquet in honour of President Xi Jinping. But what should complicate a simple reading is that Fu Manchu is unmistakably the true hero of the books. He is a dignified and even sympathetic character, while the good guys – square-jawed, pipe-smoking colonial troubleshooter Nayland Smith (“He also saved the British Empire, by the way”) and his amanuensis Dr Petrie – are tweedy buffoons in comparison. More Boris than Bond.

For while Asia seems to be demonised in the Fu Manchu books, it is in fact idealised (“this man whose ancestors had been cultured noblemen while most of ours were living in caves”) and whereas the denigration is unconvincingly trowelled on, the admiration is often unexpected and seemingly heartfelt. An early clue to Fu Manchu's essentially admirable character is that he always keeps his word, and trusts his English adversaries to do the same.

And when, at the end of the first book, The Mystery of Dr Fu Manchu, Police Inspector Weymouth has become insane after exposure to Fu Manchu's psychotropic fungi, Fu Manchu voluntarily restores him to health out of what Petrie perceives to be “some kind of admiration or respect”.

The books continue in a series of richly ludicrous adventures that ultimately play out as a romance of increasing mutual respect between the two sides. Comforted by his pet marmoset Peko, and sustained by his longevity serum, the supposedly fiendish Doctor works for world peace in the 1930s by assassinating Fascist leaders and arms manufacturers, and finally ends up as a crusader against Communism. If any further proof were needed that he is really a sterling fellow, the Doctor knows his Shakespeare, he has an implicit respect for the British gentleman's code of honour and he even turns out to have been on surprisingly chummy terms with Lord Kitchener, “whom I knew and esteemed”.

It is tempting for modern writers to produce more Fu Manchu stories, and it seems like an obvious contemporary requirement that the original scenarios should be subverted in various ways, but the original stories already subvert themselves, as well as being unintentionally very funny in places. Entrepreneur and cultural figure David Tang has written “I have read all of [Rohmer's] Fu Manchu series, whose first editions I have collected, and have had a great deal of laughter from them, although some of my compatriots, as well as many non-Chinese, regard Rohmer's characters as racial stereotyping of the worst kind. I couldn't disagree with them more.”

These magnificently absurd books, glowing with a crazed exoticism, are really far less polar, less black-and-white, less white-and-yellow, than they first seem. And as for Rohmer's most famous creation, by the internal logic of the books he should still be alive; still taking his longevity serum and still secretly scheming.

He has ensured the survival of his creator, who told listeners to a 1930s wireless broadcast: “I hope you understand Dr Fu Manchu as I have tried to understand him. Perhaps one day he may conquer the world.

“It would be a queer world, but I am not sure that it would be any worse or any better than the one we live in.”

'Lord of Strange Deaths: The Fiendish World of Sax Rohmer', edited by Phil Baker and Antony Clayton, is published today (£25, Strange Attractor Press)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments