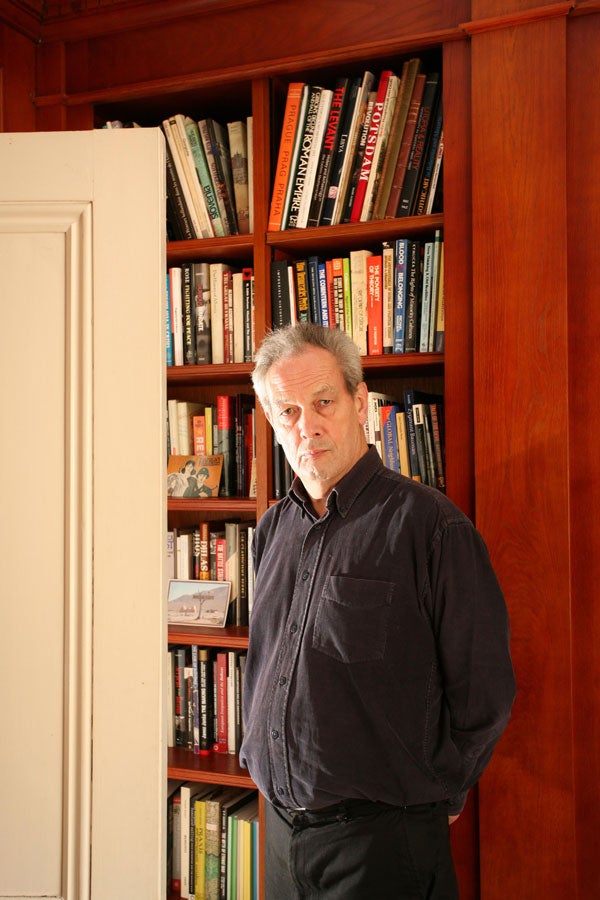

From Tory to Turkey: Maverick historian Norman Stone storms back with partisan epic of Cold War world

Boyd Tonkin meets a cosmopolitan conservative

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It isn't every day that one interviews a figure described on an official British Council website as "notorious". That badge, which this fearsome foe of drippy-liberal state culture will wear with pride, comes inadvertently via Robert Harris. In his novel Archangel, Harris created the "dissolute historian" (© the British Council and our taxes) Fluke Kelso: an "engaging, wilful, impassioned and irreverent" maverick on the trail of Stalin's secret papers.

Just back from his academic base in Ankara (he can leave at first light and reach his Oxford house by lunchtime), Norman Stone - Fluke's alleged original - does cause a little flutter in the dovecote of the Penguin offices by asking for a whisky from our hosts. Eventually, they oblige with a bottle of Bell's. Notorious enough for you, British Council folk?

Now 69, Stone still lives up handsomely to all those other adjectives. The Glasgow-born former professor of history at Oxford has since 1997 taught international relations at Bilkent University and directed its Turkish-Russian Centre. In person, as in print, his conservative polemics belong more to the partisan age of his former patron Margaret Thatcher than to Cameron's new blue-and-yellow coalition dawn. Yet they coexist with a globe-spanning breadth of vision, an insider's relish for a dozen cultures from Hungary to Haiti, and a wit and warmth that put the fun into free-market fundamentalism. His company, need I add, proves just a trifle livelier than time spent on the average British Council committee.

Posthumously-born son of an RAF pilot killed in action, a scholarship boy at Glasgow Academy, Stone as a multi-lingual Cambridge researcher and lecturer dug deep and at first-hand into the Cold War intrigues of central Europe. His pioneering work helped tilt British perspectives on the Great War east towards Germany and Russia. He also managed, in his first marriage, to wed the niece of Haitian strongman "Papa Doc" Duvalier's finance minister. Their son is the thriller writer Nick Stone; he has two other adult sons from a second marriage.

Just now, the famous polyglot with two handfuls of tongues already under his command thinks that he has "one language still left" in him. So the great Turcophile is learning modern Greek. He's delighted that its word for "laundry" turns out to be something not too far from "catharsis". But then Stone does know a thing or two about purging or cleansing – not to mention the pity and terror that accompany it. And he has lost none of his relish for language. He regrets that modern Turkish has, thanks to the language edicts of Kemal Atatürk (along with Mrs Thatcher, another strict reformer who rates his respect) shed many "splendid old words" from its Ottoman heritage. An example? A unique term that translates as "just about supportable looseness of the bowels".

Stone's star has shot (and sometimes exploded) across the firmament of British history ever since his 1975 study of The Eastern Front. Books, articles and statements have stirred the pot of historical controversy over the ravages of Soviet Communism, the follies of its Western apologists, or the fate of the Armenians in his second home of Turkey. On that score, the man sometimes branded as the voice of Ankara says nothing to downplay the Armenians' suffering during and after the massacres of 1915.

Still, he resists the "genocide" label: "Can you compare it to what happened to the Jews? I don't think you can." He does believe the Turkish state could offer a mea culpa on another front: "If there's something the Turks might apologise for... it's chasing out the Greeks in 1955. That would worth making a unilateral gesture: saying I'm sorry."

Stone has a genius for raising storms and riding them: from the celebrated essay in 1983 that scuppered the reputation of pro-Soviet historian EH Carr to his cheerleading press articles during Mrs T's years of pomp and his flight from Oxford to Ankara, casting farewell aspersions on the hygiene as well as diligence of undergraduates beside the Isis. His career abounds in paradoxes, none knottier than the period in which this nomadic Scottish cosmopolitan spent advising Mrs T – the empress of Little England – on foreign affairs during the "extraordinary time" of her 1980s heyday. That era, he believes, saw her government achieve "tissue regeneration" for a moribund nation: a verdict close to the heart of his new "personal history" of the Cold War, The Atlantic and its Enemies (Allen Lane, £30).

Wandering, opinionated, mischievous, the book is strung between two downfalls, that of the Third Reich in 1945 and the Soviet empire in 1989. Stone's vagabond history rattles across one world-shaking scene of upheaval after another, from the Moscow-backed putsches of the late 1940s in eastern Europe via the 1960s' feast of fools and the 1970s convulsions that led to the later triumph of Thatcher, Reagan and Pinochet to the unpredicted foundering of Soviet power: Stone's terminus, and his final vindication in the face of gormless academic fellow-travellers.

"Amazing, isn't it?" he recalls with a laugh. "That Sovietological establishment got extremely pleased with itself – and, ooh, they had egg on their faces. I remember some fool saying that Solzhenitsyn et al were simply not a good guide to the Soviet Union. And someone else said to me, 'You've got to read Pravda carefully'. His punishment would be to do just that!"

The book bristles with gleeful passages of lefty-baiting provocation. Poor maligned General Pinochet "deserved well of country"; the army takeovers in Chile and in Turkey might each count as a "good coup"; 1968 counter-culture brought "an explosion of imbecile hedonism"; Jimmy Carter (especially reviled) sent "bossy women to preach human rights in places where bossy women were regarded as an affront"; while, at home, Dame Mary Warnock – who sinned by scorning Thatcher's voice – embodied "the long-bottomed-knicker progressive Edwardian world" that Maggie came to bury.

In these moods, part-Evelyn Waugh, part-Jeremy Clarkson, Stone just loves to goad the liberal left. Yet they alternate with hard-headed analyses of the financial shifts behind political façades (with a brilliant account of how Saudi oil-price manipulation helped sink the Soviet Union), virtuoso sketches of pivotal events (such as Papa Doc's funeral) and enthralling, colourful swerves into memoir. These range from his own trial after a refugee-smuggling adventure on the Austrian-Czech border and scrapes in a Bratislava jail to portraits of modern Istanbul: "In Galata the techno music stopped somewhere around 3am and then, with dawn coming up over the Bosphorus, the first (from his accent, Kurdish) muezzin... cleared his throat very audibly and charged full-tilt, followed by ten others, for a good hour". Although Stone repudiates the idea, quite a few readers might wish that this "personal history" had itself run full-tilt into autobiography.

Praising the "Golden Eighties" as we talk, Stone chuckles that "it had all the right enemies". The ding-dong battle of ideologies sets his book's creative juices flowing. When I mention that early-1980s Britain might have tried to modernise itself by consensus rather than pitched battles, he replies that "I wish there had been more head-to head battles", qualified by a rapid "perhaps I shouldn't have said that...".

Above all, The Atlantic and its Enemies will strike many readers not so much as a reactionary as an anti-liberal – or even more, an anti-hippie - work. Stone has some time for high-level Marxist thinkers such as fellow historian Eric Hobsbawm, to whom he has sent a copy of the book "with a respectful dedication": one capo saluting the chief of a rival clan, perhaps.

Above all, he detests populist stupidity and the erosion of educational standards. But I wonder if his philippics have their roots in the kind of sharply adversarial "culture wars" that matter less and less to many people now. "I suppose we've moved on," he says. "For instance, with Eric Hobsbawm I wouldn't have had a culture war – we'd have been reading the same books and I much admire what he writes... As for a culture war against something like the Sixties, I think that is in a sense still with us: it's a matter of upholding standards.

"I don't think that has gone – not by a long way. So that I, and vast numbers of other people in this country, will be just appalled to think of the Tory party conference opening up with some wretched rock music. Bring back 'Land of Hope and Glory."!

The book laments the murder of the grammar schools, but says nothing about the lifelong curse of 11-plus failure that first led to the comprehensive policy he now deems to be "pretty much a disaster". Stone accepts that "reforms needed to be made" to post-war state schooling: "But it didn't mean that the system needed to be abolished".

He recalls that "I did a hell of a lot of teaching over that period. You can more or less date the comprehensive change, because you knew when undergraduates stopped spelling properly. I had to start correcting spellings round about 1980." He is shocked that, at an Oxford college, one of his sons became known as an oddball: "the boy who listens to classical music. That is very extraordinary".

Now, 13 years after his own escape from Oxford, he's still pleased by his Turkish students on the elite campus of Bilkent, and has just lunched with two scholarship-winning alumni in London. If a few of them do resemble the vacant divas of 1960s Italian art films ("a splendid looking girl with long blonde tresses and utterly empty eyes looking out over the Bay of Naples from Capri"), or else come in the form of stolid Turkish nationalists who "look like Second and Third Murderer" in Macbeth, then elsewhere he will mostly encounter "a row of bright faces" who "do turn out very well".

Turkey, more or less in Europe but only intermittently of it, supplies some of the most audacious sections of The Atlantic and its Enemies. Stone's Turkish vantage-point allows him to launch into cross-cultural leaps that make his history an exhilarating read, even when its liberal readers will be tearing out handfuls of hair. He connects, for instance, Kurdish nationalism with its Scottish counterpart and defines the double identity he shares with Kurdish friends: "Yes I'm a Scot, but I'm also British, and the British would easily come first." He enumerates the crimes of the Kurdish militants of the PKK, argues that the army "never behaved as badly" as the rebel guerrillas, and when we talk takes issue with Harold Pinter and the human-rights defenders of the well-meaning West: a recurrent bugbear in his book. "Like anybody who's connected with the theatre, or at least anybody who's any good connected to the theatre, he talked drivel about politics." Note that "anybody who's any good".

Stone can even find warm words for the "therapeutic" army coup of 1980 that (for him) set Turkey on its course towards modernisation and prosperity. "One doesn't like to defend military coups," he says, "but if you were the parent of small children in Ankara in 1979-1980, used to hearing the gunfire coming from this quarter and that, with queues for everything and the lights going out, you'd say 'Thank God for the army'."

After the interview and the election, I email Stone to ask his opinion of this week's frantic manoeuvres over "political reform" at Westminster. In return, decisive action by the top brass gets another glowing reference from him. "Off the cuff", he replies, "the whole thing just shows what a bad thing it is that we don't just change the rules such that each constituency has to have about 500,000 people". We should "cut the number of MPs to about 350" and double the pay of the remaining members - "but that might mean getting some Turkish generals to do their stuff". Somehow, I can't see either the blue or yellow flank of our own incoming regime signing up for that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments