From Sophocles to Sylvia Plath, writers have long appealed to our fear of mental illness

Their tales do more than simply grip us, says novelist Ann Morgan, they help us to see mental illness as a sliding scale on which we might all at some point find ourselves

When I was growing up, mental illness petrified me. In the early 1990s, a rash of widely reported random killings by paranoid schizophrenics led to discussions about failings in community care. Headlines bristled with words such as "rampage" and "frenzied". There were soundbites on the news from people worried about venturing into shopping centres for fear of being attacked by strangers acting on the instructions of evil voices in their head.

But in my own case, the anxiety came from a different source to that troubling most of the people interviewed on TV. The thought of being attacked by a mentally ill stranger didn't scare me any more than the many other upsetting things the nightly news beamed into my living room. Instead, it was the idea of losing your mind, to the extent that you might unintentionally kill someone, that frightened me.

The knowledge that it was possible to be driven to such extremes by your own brain kept me awake for nights on end. I couldn't imagine what I would do if it ever happened to me. Some years later, when I read King Lear at school, I could well appreciate the panic in the ageing monarch's appeal: "O, let me not be mad, not mad, sweet heaven! Keep me in temper. I would not be mad," and the poignancy of his statement when, at last, he is reunited with Cordelia: "To deal plainly, / I fear I am not in my perfect mind."

King Lear is not alone in its association of fear with mental illness: in the more than 400 years since the play was written, numerous authors have yoked insanity to dread. Several 19th-century novels feature figures (usually women) in turbulent mental states who do unnerving things, among them Charlotte Brontë's Bertha Rochester – the original Mad Woman in the Attic – and the title character in Wilkie Collins's The Woman in White. More recently, the idea of the vicious madman has underpinned countless horror stories and thrillers, with Robert Bloch's Psycho being something of a touchstone.

These stories are suspenseful and often chilling because of the inscrutable nature of the afflictions gripping their characters. We don't understand what is wrong (at least at first) and so we can't predict what will happen next. And the less we understand, the more easy it is to demonise.

It's a technique that the author Shirley Jackson exploits and to some extent turns on its head in her terrifying mid-20th-century novel The Haunting of Hill House. Here, rather than being rushed at on occasion by an insane character who waits in the wings, readers are taken inside the mind of the person who is disturbed. The troubled protagonist is Eleanor, one of a handful of volunteers who answer a newspaper advert to accompany an investigator of the paranormal during a stay at a purportedly haunted house.

The not knowing in this case takes the form of an uncertainty about how many of the unsettling events described are real and how many of them only take place in Eleanor's mind. Although there are suggestions in the weird euphoria that Eleanor feels during her journey to the house that her mental state is erratic, Jackson lays out enough hints to keep open the possibility that the terrifying occurrences that the guests all experience to some degree have supernatural causes. As a result, we wander through the text as ill at ease and unsure about what is really happening as the protagonist herself. The final turn of the screw comes when Eleanor's anxieties transform into a horrid serenity that we know with queasy certainty can't come to any good.

Jackson might have left things at that and turned in a gripping thriller. But what lifts the book on to another level are the flashes of insight that she continues to give Eleanor right up until the narrative drives to its terrible conclusion. Amid the eerie incidents, we get glimpses of the woman trapped in the tumult, clamouring to get out. This is what makes us care and keeps the story churning in our brain long after the final page.

Indeed, this issue of where a condition – or perhaps possession in Eleanor's case – stops and the person begins is one of the most fascinating questions when it comes to the literature of mental illness. From Bessie Head's A Question of Power to Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar, and from Horacio Castellanos Moya's Senselessness to Knut Hamsun's Hunger, the world abounds with novels that tug at the knots tying identity to mental health and try to tease out the point at which the concepts come apart.

Many of these, such as Iris Murdoch's tour de force The Sea, the Sea, work through the form of intense, first-person narratives that seethe with contradictions and non sequiturs, inviting readers to put their own spin on events and make their own diagnosis. Others, among them Vladimir Nabokov's Pale Fire, use devices such as footnotes to build up layers of assertion and counter-assertion that wrinkle into pockets where speculation about the sanity of one or more of the narrators can breed – a kind of textual split personality disorder.

In my novel Beside Myself, which features an identical twin who is diagnosed with bipolar disorder after she swaps places with her sister and becomes trapped in the wrong life, I decided to use voices to reflect the mental disintegration of my protagonist. Starting off rooted in the first person, the narrative comes unstuck after a traumatic childhood experience and moves into the second person. By the time the adult protagonist, Smudge, appears, the narration is in a distant third-person strain that gets interrupted – and occasionally almost overwhelmed – by disjointed voices in Smudge's head.

The seriousness of the question of how identity and illness intermingle means that many of the works that tackle it tend to be rather bleak, but that isn't always the case. Joseph Heller builds Catch-22's satire around a set of paradoxical requirements used to ascertain whether airmen are mentally fit to fly (in short: if you were insane you could be excused from duty; and yet, if you applied to be excused, you were showing a very sane fear for your life); Don Quixote's deluded tilting at windmills evokes much mirth; and, for all its sinister, Kafkaesque traits, Jonas Karlsson's The Room, about a civil servant who discovers a door to a secret office where his colleagues can see only a blank wall, packs several hilarious punches.

Similarly, for all the fears often attached to it, mental illness itself is not portrayed in a uniformly negative light in fiction. Just as it provides rich fodder for wordsmiths, so its depiction is often rich. For example, the link between mental illness and creativity – demonstrated by numerous scientific studies, including research last year by Reykjavik-based genetics company deCODE which showed that painters, musicians, writers and dancers are, on average, 25 per cent more likely to carry gene variants that predispose them to bipolar disorder and schizophrenia – is a common theme.

The protagonist of Patrick Gale's Notes from an Exhibition, for example, is the brilliant yet troubled artist Rachel Kelly, whose debilitating bipolar disorder and bursts of creative genius are irrevocably intertwined. The question is: brilliant yet troubled, or brilliant because troubled? Though Shirley Jackson's Eleanor is ultimately crushed by events at Hill House, she experiences moments of exhilaration, joy and release as she surrenders to whatever delusion or force grips her there. Even Lear, wandering on his blasted heath, "As mad as the vexed sea, singing aloud, / Crowned with rank furmitor and furrow-weeds", has moments of accepting his weakness and diminished status that approach a kind of peace.

These depictions of the positive sides of altered mental states echo some of the real-life accounts written by people diagnosed with psychiatric illness. In The Devil Within, for example, author and critic Stephanie Merritt describes how her bipolar disorder led to periods of intense productivity and an "unnatural energy" that allowed her to turn in articles at a frenetic rate, although, as the title suggests, the negative aspects of the untreated illness far outweighed any benefits. This dual quality is reflected by the fact that, in many of these narratives, those who have experienced treatment describe the struggle of accepting that managing their illness so as to be able to function on an everyday basis will involve the loss of the bursts of energy, creativity and vision that their condition affords them in its unbridled state.

There are some forms of insanity that are celebrated in literature or at least regarded as normal. Love is the prime example. Here's Romeo, a self-confessed "sick man", describing his state in light of his new feelings for Juliet, and sounding for all the world like someone in the grip of a psychiatric disorder: "Tut, I have lost myself. I am not here. / This is not Romeo; he's some other where." And more plainly, here's Rosalind in the thick of toying with Orlando in As You Like It: "Love is merely a madness, and I tell you, deserves as well a dark house and a whip as madmen do; and the reason why they are not so punished and cured is that the lunacy is so ordinary that the whippers are in love too." (Rosalind's reference to the grim Elizabethan treatments for madness are a reminder that extreme and inappropriate responses to many forms of mental illness are sadly nothing new.)

Even when it comes to less common conditions and obsessions, literature's ability to transport readers and viewers into unfamiliar and sometimes desperate situations means that it is able to explain and to some extent normalise the troubled mental states of its characters. Through showing us the steps that have led to the crisis, stories reveal that insanity can often be if not a rational then a reasonable, human response to terrible events. For example, in Sophocles' play Electra, Electra's plan to have her brother Orestes murder their mother Clytemnestra is somehow understandable in light of her fixation on her dead father and hatred for the mother who killed him. Similarly, some 25 centuries later, in his novel The Shock of the Fall, Nathan Filer's deft excavation of the impact on the protagonist of his brother's death takes us deep into the experience of schizophrenia.

Stories such as these are important because they build bridges between the world of the reader and that of the character described. By revealing the humanity and humanness of illnesses so often stigmatized and made to seem other, they chip away at the sharp divide many of us imagine between sane and insane – a divide that may often be little more than a comforting buffer between us and the terrifying idea of losing our mind. Instead, these stories encourage us to see mental health as more of a sliding scale, a continuum on which we might all find ourselves at different points throughout our lives. By fleshing out the experience of mental illness, they nudge us towards the truth that, as Matt Haig observes in his memoir-cum-manifesto Reasons to Stay Alive, "Everyone would have a label if they asked the right professional." In so doing, they work against the stigma and fear that so often bring loneliness in their wake for people diagnosed with mental illness.

This was something I encountered in my early-twenties when I spent two years volunteering for Samaritans. Over that time, I had the sad privilege of talking with people in all sorts of extreme circumstances, from young abuse victims in care to prisoners experiencing mental breakdown, as well as many people holding together "normal" lives while struggling against terrible challenges beneath the surface.

The stories of those I spoke to were unique and private to the individuals, but something that was common to many of them was a sense of isolation. Even those in touch with the caring professions often felt failed and marginalised by the system, something I later found movingly conjured in John O'Donoghue's memoir Sectioned: A Life Interrupted. Yet these people felt a compulsion to share their own stories and to feel the connection that doing so brings – even if the only person listening is a 23-year-old stranger on the end of a telephone line. And if sharing stories on an individual level can foster that sense of affinity, however brief, then sharing them on a national or international level through the archetypes, everymans (and everywomans), and vibrant one-offs of literature can surely link us – more of us – yet more meaningfully, and help to break down the preconceptions that keep fear and stigma entrenched.

Of course, this is not to suggest that literature by itself can be the magic bullet for the failings in the way we handle mental illness. After all, human beings have been telling stories about mania, obsession, depression and delusions for centuries, and we still are a long way from understanding and accommodating these states in society.

Indeed, the form of stories makes them in some ways unsuited to carry the full weight of the experience of mental illness. Beginnings, middles and ends bear little relevance to the daily lives of many who endure psychiatric conditions that can often seem punishingly endless. It's a point that Rose Bretécher makes in Pure, her account of living with "pure o", a little-known form of obsessive compulsive disorder: "The global story bias has no truck with the grinding tenacity of mental illness: when was the last time you saw a drawn-out soap opera storyline in which someone spent years bottling something up before finally mustering the strength to confide in a loved one, and then literally NOTHING CHANGED?"

Books that attempt to capture something of the interminable nature of such situations can never entirely succeed. Even Hanya Yanagihara's 720-page, best-selling novel A Little Life, a substantial portion of which is devoted to the appalling history of the compulsively self-harming Jude St Francis, cannot do this justice; the days or weeks it takes to read are as nothing beside the decades facing those for whom such experiences are a bitter reality. While John Bunyan's Christian passes through the Slough of Despond and comes through his trials to declare triumphantly at the end of The Pilgrim's Progress, "My marks and scars I carry with me, to be a witness for me that I have fought His battles who will now be my rewarder", many spend much of their lives trapped in the swamps, with little hope of moving forward.

Despite its limitations, however, literature is a powerful tool in the effort to help us to all live better with mental illness. By taking us inside a world that we instinctively fear and wish to distance ourselves from, stories remind us that while people sometimes lose their minds, they never lose their humanity. This brings with it a string of powerful implications: that psychiatric illness is tightly woven into the human experience. That we all have psychological marks and scars. And that, when it comes to mental health, there is a continuum where we might prefer to imagine a neat divide. Ultimately, they encourage us to confront the alarming yet liberating truth that the "perfect mind" does not really exist.

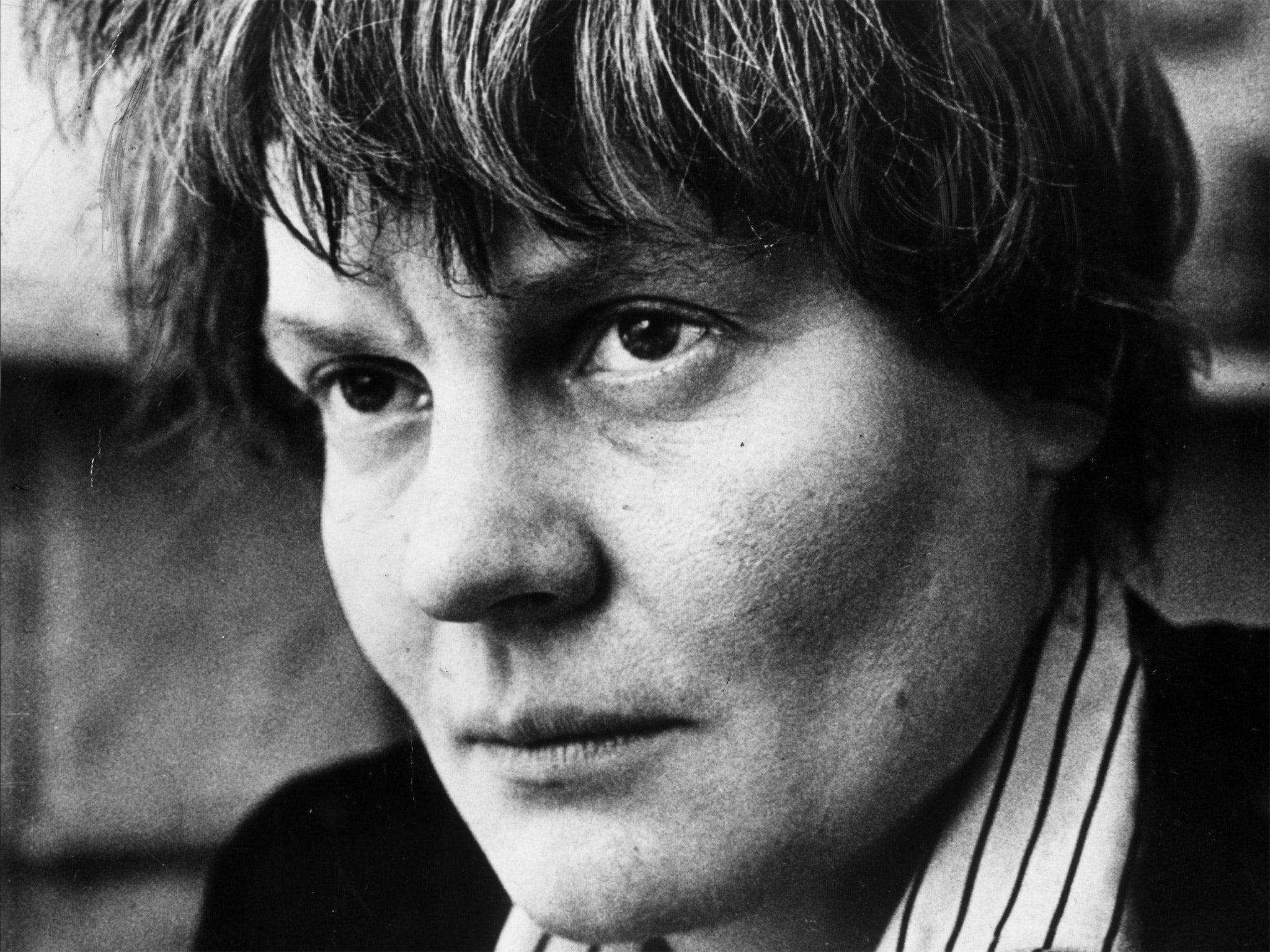

Ann Morgan's novel 'Beside Myself' (£12.99, Bloomsbury) is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks