Elementary, my dear boy: An investigation into Sherlock Holmes' early years

Arthur Conan Doyle never explained why his most famous creation was a 'drug-addicted bipolar maverick' – but Andrew Lane, the author of the new Young Sherlock Holmes series, is following a few leads...

A question you may never have thought to ask yourself is, "What do Doctor Who and Sherlock Holmes have in common?" Until recently, you would have been right in assuming that there was little to link the Time Lord with the eccentric, logical sleuth – but there is soon to be a permanent connection and his name is Andrew Lane.

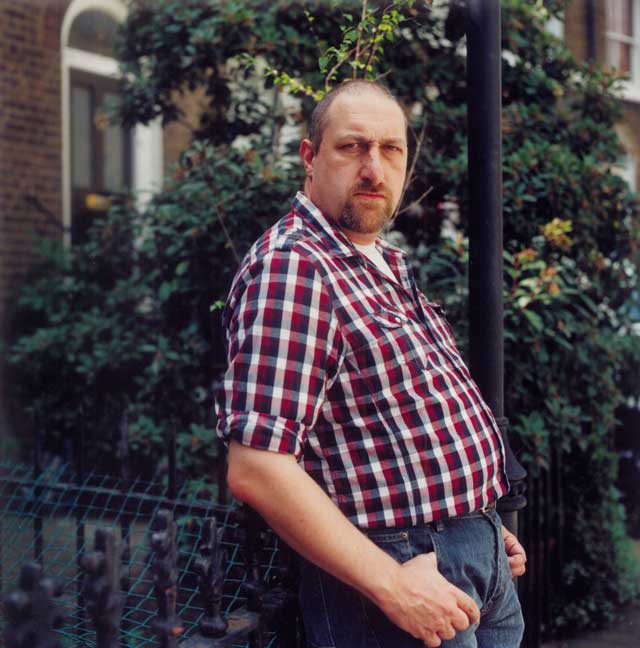

He's an interesting fellow. At the age of 12, Lane spent his pocket money on a couple of second-hand books at a church jumble sale, one of which was a 1930s hardback copy of Arthur Conan Doyle's first Sherlock Holmes novel, A Study in Scarlet. Thus began what has become a life-long fascination, bordering on obsession, with Baker Street's most famous resident. The link, however, is that he has also been the writer of a string of Doctor Who spin-off novels, not to mention a whole raft of television- and film-related non-fiction work, and he is now the author of a new Young Sherlock novel, Death Cloud. That he is also a full-time civil servant seems of only minimal interest to the man himself.

There is an odd fact about the Conan Doyle estate, which is that while his works are out of copyright in the UK, they are still, just, in copyright in the US. This led to Paramount television ending up in a slight pickle some years ago when they made two episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation with Holmesian story lines and fell foul of copyright infringement laws. As Lane puts it, "I don't think those episodes will ever be shown on TV again."

It was because of the copyright issue that the idea of a series of Young Sherlock novels was first mooted. Lane explains that, with the US copyright due to expire, the estate and the family (descendants of Conan Doyle's brother) feared "a flood of Sherlock Holmes stories". Thus they started to think about how they could establish a series of authorised works to protect the brand.

While there are hundreds, if not thousands, of works based on the detective as an adult, his childhood has hitherto remained curiously untapped. In fact, only the 1985 Steven Spielberg-produced film Young Sherlock Holmes, and a short-lived Granada TV series that predates it, are set in Holmes' youth. Lane explains that the latter is "an Enid Blyton sort of Sherlock Holmes. It's all mystery in the manor house or smugglers' coves, whereas the Spielberg version is much darker, bordering on science-fiction or fantasy, and much more Gothic."

The Conan Doyle estate therefore decided that Holmes' childhood would make suitable material for a new strand of stories, and Lane, with his passion and encyclopaedic knowledge of the works, was selected as the obvious choice of writer.

What Lane picked up on in the film version was the presence of John Watson as a childhood friend of Holmes, which is somewhat at odds with A Study in Scarlet, in which Watson is introduced as a badly injured veteran of the Afghan War, short of money and looking for digs in London. This anachronism jarred with Lane and informed his thinking. "I wanted the books to be realistic in the historical approach; I didn't want pastiches that sold the character short.

"In the 10-page proposal that I put together, it was important that the series took Sherlock from being a 14-year-old boy at school, through university, and leads seamlessly to the opening lines of the first of Doyle's Sherlock novels. I didn't want them to be seen as period pieces with Victorian wood-cut-style covers, but as contemporary, 21st-century books."

Thoroughly modern the new book appears too; but how does Lane respond to those who might accuse him of jumping on the bandwagon started by Charlie Higson's Young Bond series "I don't think we started out thinking about the commercial possibilities of this at all," says Lane. "If we had really wanted to attack the market I think we would have gone for 'Sherlock Holmes vs the Zombies', 'Sherlock Holmes vs Vampires' and 'Sherlock Holmes and the Pirate'. I didn't want 'Sherlock Holmes: Monster Hunter'."

Lane riffs most fascinatingly when discussing those attributes of the mature Holmes that he used as a starting point for his understanding of the youthful sleuth. "What I focused on was that he has a phenomenal number of abilities, yet the reader is given no idea where they came from. According to Conan Doyle, Holmes can box to a professional standard, he's virtually a professional swordsman, an expert in baritsu – the 'Japanese system of wrestling' invented by the author – and is well versed in regional accents, tattoos and pipe tobacco. He also plays the violin."

Responding to a foolish interjection regarding Sherlock Holmes' appalling musical skills, Lane corrects me. "Ah no, Watson says he played badly only when he wanted to; that Holmes would lie on the sofa and scrape away for hours driving Watson mad, but on spotting Watson's distress, would then play a selection of his friend's favourite tunes perfectly to calm the poor doctor down."

What piqued Lane's interest most were the events that must have occurred to the junior Holmes to mould him into the character he is when we meet him at 26, or thereabouts, as Lane supposes him to have been. "What I want to show is not only how he learns this range of abilities, but also what made him the obsessive-compulsive, drug- addicted bipolar maverick that contemporary medicine would diagnose him to be. I'm really interested in the two sides of Holmes: the split personality of the logical, analytical, thoughtful aspect of him, and the opposing bohemian, violin-playing, artistic side that allows him stay in bed for a week." Lane is equally interesting when asked about Holmes' relationship with women – or rather, the curious lack of any meaningful one (notwithstanding the continuing disputes in Holmes studies around the character of Irene Adler).

"You can't have a decent book without a strong female character," says Lane. "But being set in Victorian times, the status of women in society then precluded my taking the Enid Blyton Famous Five path. This made it very difficult to give Sherlock a female companion who would be able to do all the things he did."

He seems to have managed rather well, though, through a character called Virginia – a wonderfully feisty, well-drawn, red-headed, American girl – despite claiming that there were many moments in the writing of Death Cloud when he had struggled to "find ways of squeezing Virginia into the action". That the mature Holmes is bereft of any noticeable female companionship and has a distrust of women makes one fearful for her future in the books to come. All Lane will say on the matter is a rather gnomic "something happens", beyond which he refuses to be drawn.

When talking about the path to publication, he is effusive in his praise for publishers Macmillan, who he says understood what he wanted to do from the off. The relationship was helped in no small part by his editor, Rebecca McNally, who has form in this arena, having played a key role in the publication of the Young Bond series. It was she who pitched the idea to the powers that be within Macmillan and maintained the firm line taken by Lane and the Conan Doyle estate that this had to be "the real Sherlock Holmes in a real Victorian world".

Lane has a three-book deal with Macmillan and Death Cloud will be followed in six months' time by the second in the series, in which Sherlock faces the repulsive Red Leech. That story is set in part in the United States and will no doubt do wonders for sales, not to mention the possibilities of a film adaptation.

Given Lane's sense of respect for Conan Doyle's work and his impressive grasp and understanding of Holmes' character, there can be little doubt that he and Macmillan are in line for great success. A young reviewer whose opinion I sought, Josh Hamwee, aged 11, enjoyed it so much that he concluded it would be worth the risk of "sneaking it into chapel". The book, though, should impress the detective's fans of all ages. No "shit Sherlock" this, but an elementary success story.

The extract: Young Sherlock Holmes: Death Cloud, By Andrew Lane (Macmillan Children's Books £6.99)

'... A flash of colour through the trees caught his attention: red spots on a white background. He moved closer, thinking it was a clump of toadstools breaking through the ground, but there was something about the shape that bothered him. It looked like ... A cloud of smoke began to rise from the object just as Sherlock recognised it for what it was: a man's body, lying twisted on the ground'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks