Did Dickens send his illustrator to his death? Or is that fiction? Week in Books column

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

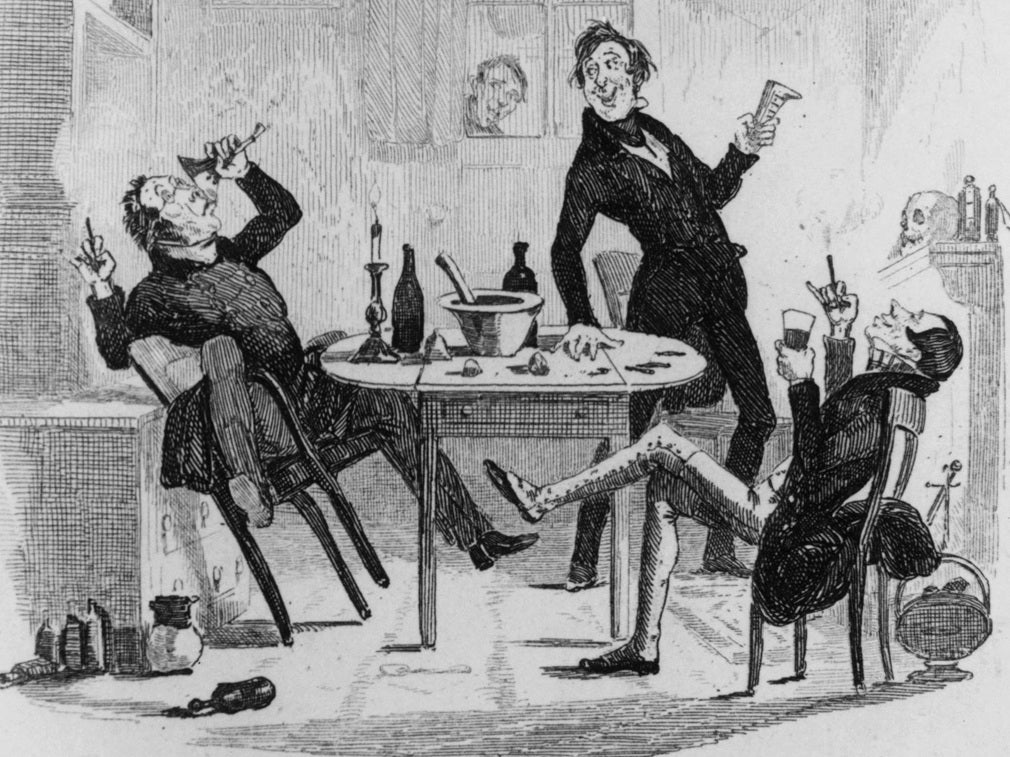

Your support makes all the difference.The integrity of Charles Dickens is in question (again). This time, not over an illegitimate child with the mistress or the rapacious moneymaking, but over the claim that he stole key ideas for his first novel, The Pickwick Papers, from his illustrator, Robert Seymour, who committed suicide shortly after this alleged creative theft. Death and Mr Pickwick is a novel but its author, Stephen Jarvis, says he is writing “faction” – fact-based fiction – with evidence to bring Dickens’s character into question.

As historical revisionism goes, the book clearly hopes to correct every cough and spit of this episode in Dickens’ career, at 800 pages. I do wonder if it began life as non-fiction, but the author decided that faction was better at covering over the cracks of uncertainty. I haven’t read it but I have spoken to Jarvis, whose interest was piqued by a single mention of Seymour in the novel’s preface. He feels that Seymour was undermined by Dickens. It was Seymour, he says, who invented Mr Pickwick and his Club of Cockney Sportsmen, and his illustrations were to take primacy over the accompanying text, until Dickens came along with his “pack of lies”.

Jarvis’s evidence includes the fact that Dickens claims to have met Seymour once, though the illustrator’s wife said otherwise; and that Seymour burned some Pickwick images shortly after a meeting with Dickens, and shortly before he killed himself. An American called Samuel Lambert apparently tried to unpick the facts around Seymour’s death before Jarvis, in the 1920s, but was attacked and dismissed by the Dickens Fellowship. Jarvis should probably brace himself.

Literary figures to have had their lives “rewritten”, counterfactually, or fictionally, are many, from Jane Austen to the Brontës, and the more recent, colourful accounts include those of Ernest Hemingway (from the point of view of his long-suffering ex-wives) and Virginia Woolf; these lives contain a combination of glamour and tragedy that makes them eternally fascinating to us.

Gaps will always be found where inconsistencies can be planted and grown. Revisiting the lives and words of figures long dead is mainly a safe bet because it is often the gaps in their lives that are contested, and these can’t be filled with irrefutable evidence: so instead they hinge on what the wives of Hemingway said to their friends, or, in the case of Dickens’s illegitimate child, what Dickens’s mistress said. Louisa Price, curator at the Dickens Museum, reminds us that the character and motives of these secondary figures must be questioned before a revisionist account is to be accepted.

In the case of Seymour and Dickens, the central mystery seems to hinge around a meeting on 17 April 1836, which must have ended amicably – Dickens arranged a drink in the pub with Seymour and his publishers, Chapman & Hall, for the following Sunday. But Seymour killed himself before that. Were the two incidences part of a single chain?

Not according to Price, who points out that Seymour was a troubled man with many demons beating at his door (anxiety, illegitimacy, and more) and also that the museum has a permanent exhibition on copyright which stands as testimony to Dickens’s active and pioneering role in establishing the protection of ideas for authors in the 19th century.

Interestingly, her version of Seymour and Dickens’s collaboration seems to have only a few inflected differences to Jarvis’s account, which makes me wonder whether this is not just about ways of seeing. She agrees that it was Seymour who proposed the idea of “The Laughable Misadventures of a Club of Newly Affluent Cockney Sportsmen” to Chapman & Hall, and a series of illustration plates to which Dickens was originally commissioned to write 12,000 accompanying words. Until Dickens persuaded the publishers to give him creative licence and do it the other way around. So Seymour might well have felt sidelined, but does it count as creative theft?

We could borrow some good ideas from the isle of Orkney

There is now a good reason to go to Orkney, other than for the wind and rain and sheep-grazed expanses; we should all take a trip to the island’s award-winning library, picked out as the library of the year this week for The Bookseller’s industry awards. It’s surely worth sitting in a train carriage for the many, many hours it would take most of us to learn some precious lessons in how to keep the wonderful art of borrowing books alive.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments