One-hit wonders: Why some authors get stuck after their debut novel

With the winner of the illustrious Desmond Elliott Prize for best new novel announced this week, Charlotte Cripps looks at why some authors buckle under the strain, take forever or just don’t have it in them to write that elusive follow-up

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The pressure to write a second novel after a glittering debut can leave an author in total panic or full of confidence. The blank computer screen awaits, and the sense that the writer is expected to impress again, which is why Second Novel Syndrome is something that most authors identify with.

This is of particular relevance this week, as the winner of the Desmond Elliott Prize, the UK’s most prestigious award for first-time novelists, was announced, with a prize of £10,000 and the expectation that its recipient will sit down and write another book.

“They are not under any contractual obligation to write another word, but the hope is that the prize will encourage them to work on a second novel – and reassure them that it will have a ready readership,” says Alan Hollinghurst, who won the Man Booker Prize in 2004 for The Line of Beauty, and is head of the Desmond Elliott Prize’s judging panel.

“I was very lucky, in that my first novel [The Swimming Pool Library in 1988] had been a bestseller in both Britain and the US. I think the sense of encouragement probably outweighed the usual doubts when it came to writing a second novel, which I knew I wanted to be different, in setting and mood. I recall it was a difficult beginning, but once I’d got started I wrote it with a kind of pleasure and absorption that I envy today.”

Famous past successes include Irish novelist Eimear McBride, who won in 2014 for A Girl is a Half-formed Thing, which also took the Women’s Prize for Fiction and went on to become a major commercial and critical success. All of the winners, since the prize was launched in 2007 for debut books published in the UK, have written subsequent novels, except for Francis Spufford, who won in 2017 for his book Golden Hill, which also earned the 2016 Costa First Novel Award – although he is currently working on a new novel (and has completed an unauthorised, unpublished addition to CS Lewis’s Narnia series).

And this year’s winner is Claire Adam for her book Golden Child – a family drama set in the “colourful and dangerous world of her childhood”, Trinidad. According to Hollinghurst, the book is “a superbly controlled narrative of a family cracking under unbearable pressures, and a remarkable study in violence, always latent, sometimes horrifically real”. But will these winners go on to write great books or find it’s just been a matter of first-time luck?

Peter Straus, MD of Rogers, Coleridge and White, who worked on the Man Booker Prize for years, points out: “I think to write one extraordinary fiction is remarkable in itself and rather than bemoan a lack of a second novel, one should celebrate the first.”

In some cases, finishing a first novel can be such a gut-wrenching ordeal that the second book pales in comparison, although few instances are as extreme as that of the American writer Harold Brodkey, who is famous for taking 27 years to produce his long first novel The Runaway Soul (835 pages) in 1991 – having been commissioned to write it in 1961. He followed it up with a second novel, Profane Friendship, in 1994.

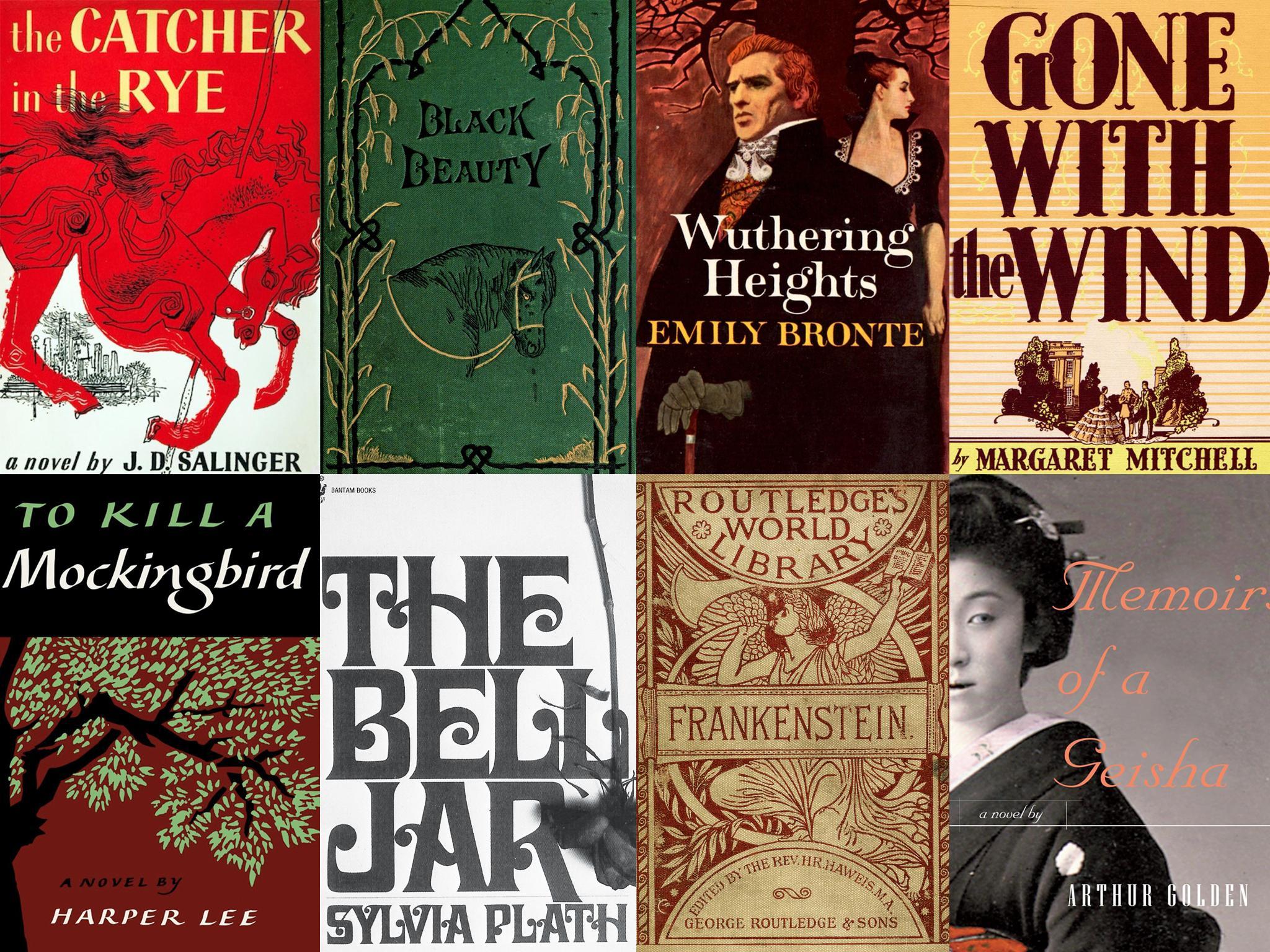

Then there are the authors who are one-hit wonders, publishing only one bestselling novel: J D Salinger followed Catcher in the Rye in 1951 with only short stories and novellas, and after Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, there was nothing from her – but when you write a classic, as Emily Bronte did with Wuthering Heights in 1847, its enduring appeal begs the question: does it matter if there’s another novel after it?

The prolific poet Sylvia Plath’s only novel, The Bell Jar (1963), which was largely an autobiographical story about her mental illness and written under a pseudonym, Victoria Lucas, was rejected several times by British and American publishers, before finding its way into the psyche of every teenager, trying to fit into the world.

Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, which was her one and only novel, published in 1960, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1961, before her estate discovered Go Set a Watchman. It was written in the mid-Fifties, and published in 2015 as a sequel, but although it worked as a standalone novel, it was part of the first draft of To Kill a Mockingbird.

Arthur Golden’s Memoirs of a Geisha (1997) was his only book, written over six years as he rewrote the novel three times, settling at last on its first-person viewpoint. It was turned into a feature film in 2005, and has sold more than four million copies.

One of the bestselling books ever, Black Beauty, published in 1877, was written by the then reclusive invalid Anna Sewell, and became an instant bestseller, with Sewell dying five months after its publication.

For other authors, it may be that they have written other novels, but they’ve only had one big hit, as Margaret Mitchell did with her final work, Gone with the Wind. It was the same story with Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front.

John Kennedy Toole, who won the Pulitzer Prize posthumously in 1981 for A Confederacy of Dunces, which was published 11 years after his suicide in 1969, had two more novels published after his death, but this was his only major hit.

Other authors have had a very long gap between their first and second novel. One of them is Arundhati Roy, who won the Man Booker Prize in 1997 with The God of Small Things, but didn’t publish another novel until 2017’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. There is an even longer wait for the second novel of New Zealand novelist, short story writer and poet Keri Hulme whose debut, The Bone People, came out in the UK in 1985 and won the Man Booker Prize. Her long-awaited second novel, Bait – which should perhaps be renamed Wait as it has taken 34 years to produce so far – is a meditation on death. But it is still not yet scheduled for publication by Picador in the UK and they are still not working with a manuscript.

Hulme, who has blamed multitasking on another book before Bait was finished and then struggling to decide between three endings, as well as other extenuating circumstances, has said: “I’m just trying to remember the name of the animal that climbs up its own tail with extreme ease, a bit like a possum – well there was that kind of effect with Bait. And – bless my publishers, they’ve been amazingly generous – I do feel derelict in my obligations. I’ve learned something not to do ever again, and that is sign contracts before you’re absolutely sure something is finished.”

Sarah Perry, who was on the Desmond Elliott Prize judging panel last year, knows only too well about writing a novel when faced with “lack of privilege and the burden of the day job”. Her first novel, After Me Comes the Flood, went somewhat under the radar before her second novel, The Essex Serpent, was a smash-hit success.

“In an industry that tends to have a bit of an obsession with debuts, anything aimed at supporting writers with developing their practice is especially welcome. I was fortunate enough to win a regional award for my debut, so I understand what a boost it is both to have the support and praise of the judges (which goes a long way towards building confidence as you work on your next book), and money to help with practical matters (in my case, replacing a broken laptop).”

Claire Fuller, who won the Desmond Elliott Prize in 2015 with Our Endless Numbered Days, has since written two other well-received novels, Swimming Lessons and Bitter Orange. She says: “I have to admit that I finished the first draft of my second novel, Swimming Lessons, before my first was even published – so I was able to avoid the pressure I might have felt in trying match its success. Any pressure I felt wasn’t so much in the writing of it, but in the reception – which luckily was good,” she says. “Having said all that, I still have to grapple with my own lack of confidence in my writing on a daily basis – I think it’s something all writers face. But reminding myself now and again that my first book won the Desmond Elliott Prize is a sure way of getting me through those slumps.”

Preti Taneja, whose 2018 winner We That Are Young is being developed for TV by the makers of Narcos, is still trying to write her second novel, and says the strain comes not from outside but within. “Pressure comes from the way characters inhabit my mind. How their voices and their ways of seeing need to find expression. It comes from the stories I want to tell, and from a sense of excitement about wanting to see what I can do with my writing. I don’t feel pressure from a market.

“Economic pressure is another thing – but when literary critical culture remains so elitist, when bookshops are run by international financiers but staffed with passionate, underpaid people, when the government’s austerity measures mean libraries are closing – for most writers, the sums don’t work.

“Whatever happens when I’ve finished isn’t up to me – the only thing I can control is the next word I write. We all know about the gatekeeping; the class, race and gender bias in the literary world, and I’m always glad when my work finds genuine allies.”

So, as the debut novelist works to pull the rabbit out of the hat once again – terrified of writer’s block or buoyed by the success of a recent bestseller – the future is always uncertain. Whether the next book will be as good as the first, nobody can tell, because it might be the 10th novel that hits the jackpot, as was the case with Hilary Mantel. She took her time climbing up to literary stardom from her 1985 debut, Everyday is Mother’s Day, before being awarded the Man Booker Prize twice for 2009’s hit Wolf Hall and the 2013 novel Bring Up the Bodies. But as any writer or agent will tell you, the only way to get through it, is to write.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments