Classic newsroom books: A memorable saunter down the Street of Shame

From George Gissing's New Grub Street to F E Baily's extraordinary Fleet Street Girl

Although the backdrop for George Gissing's New Grub Street (1891) is "the valley of the shadows of the books" (the British Museum Reading Room) and not the offices of Fleet Street, the book's inclusion in any newsroom-novels list is a foregone inclusion. This is a world marked by petty rivalries over whose review of whose novel appears in which periodical, and it is a constant struggle to make ends meet.

Fin-de-siècle fears hang heavy over the text. Fast-forward to the turn of the Millennium and the "spirit of the times" is just as cynical: print journalism marked by "soft pornography and… tittle-tattle", describes a character in Jonathan Coe's The Closed Circle (2004). "Tittle-Tattle – a magnificent title; the very thing to catch the multitude," suggest Gissing's literary folk when proposing a new paper, one full of "the lightest and frothiest of chit-chatty information," in easily digestible bite-size chunks. Although not strictly Fleet Street-set, Coe's novel does contain the most hilarious expletive-drenched response to the offer of the job of literary editor: "Political editor? No. Deputy editor? No […] LITERARY editor. Do you hear me? LITERARY – F**KING – EDITOR. They want me to commission book reviews. They want me to spend every day putting novels into f**king jiffy bags […]."

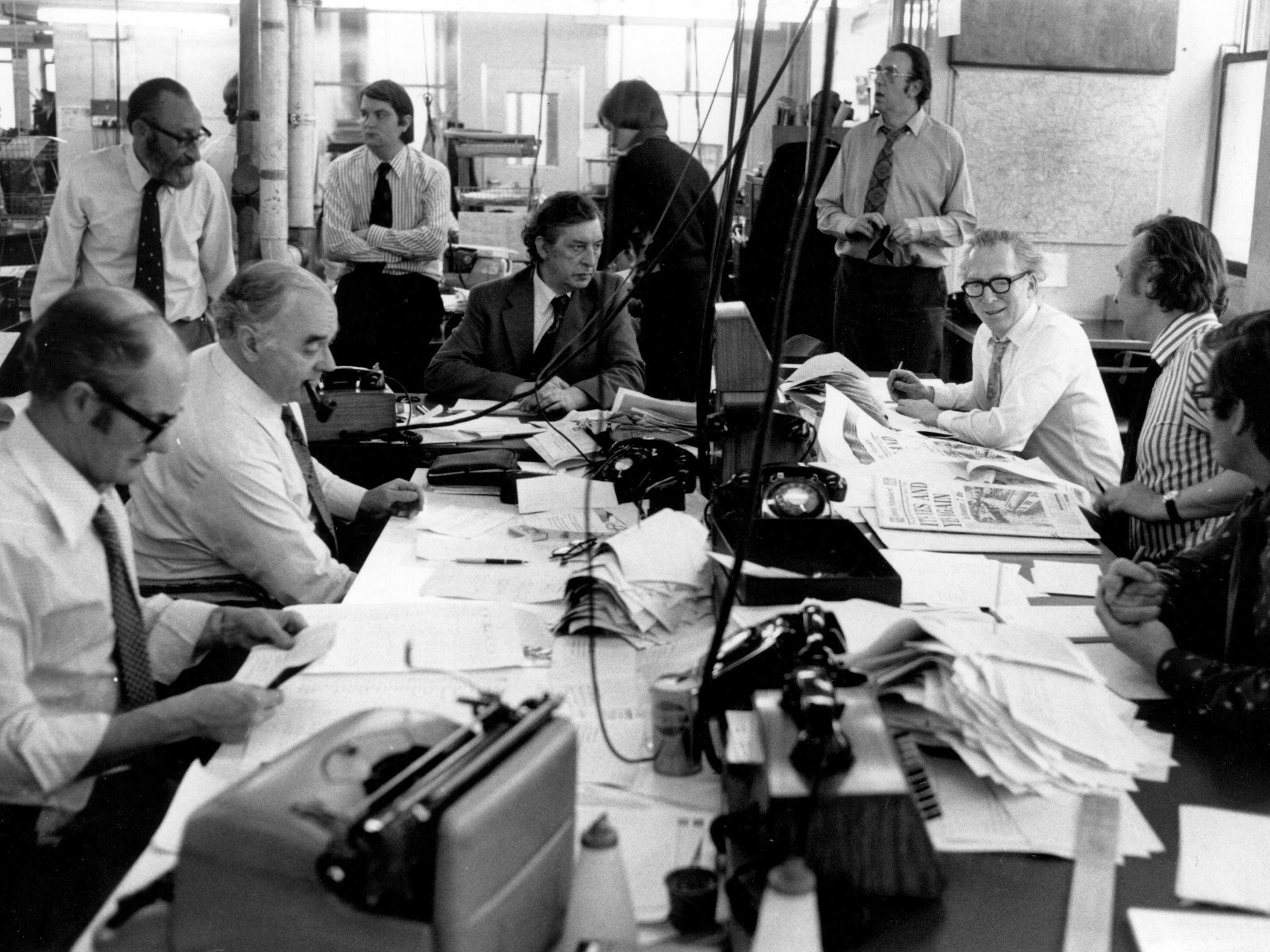

I am reminded of George Orwell on the topic: "The prolonged, indiscriminate reviewing of books is a quite exceptionally thankless, irritating and exhausting job." Meanwhile, however, in Michael Frayn's Towards the End of the Morning (1967), writing book reviews for the New Statesman is the height of sophistication. Frayn's depiction of the heyday of Fleet Street – assumed to be based on his time at The Observer in the 1960s – is summed up by this oft-quoted passage: "Various members of the staff emerged from Hand and Ball passage during the last dark hour of the morning, walked with an air of sober responsibility towards the main entrance, greeted the commissionaire, and vanished upstairs into the lift to telephone their friends and draw their expenses before going out again to have lunch."

Desperately funny in parts, Frayn's novel is closest in style to Evelyn Waugh's now legendary Scoop (1938) – so biting an account of the lengths to which Fleet Street will go for the hottest story, it has since defined satire as the newspaper novel's natural form. See also Andrew Martin's Bilton (1998), the fictional New Globe, for which the titular Bilton writes, akin to Scoop's The Beast, and the plots of each hinging on some hapless war reporting.

Joining Coe and Martin in the pre-Millennium years is Annalena McAfee's The Spoiler (2011), which sets traditional reportage – in the form of a once lauded but now past-it Martha Gellhorn-like war correspondent – up against the modern tabloids – an ambitious young hack who'll do anything for a juicy story. This is all against the backdrop of the impending internet age and a "bold new experiment" to turn a broadsheet's Saturday magazine into an online-only venture.

That McAfee – again, herself a journalist – takes women as her main characters is a much welcome break from the newspaper novel's testosterone-heavy past. A rare exception to this being Monica Dickens' (great-granddaughter to Charles) gloriously fun My Turn to Make the Tea (1951), based on her experiences as a junior reporter on a provincial paper.

One final title worth a mention has to be F E Baily's extraordinary Fleet Street Girl (1934), a secondhand bookshop find, which tells the story of a young journalist's attempts to solve "the problem of career versus marriage". Packed with earnest melodramatic speechifying – "We journalists live our lives at top-speed; even the young and strong feel the pace" – I've never encountered mansplaining like it!

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks